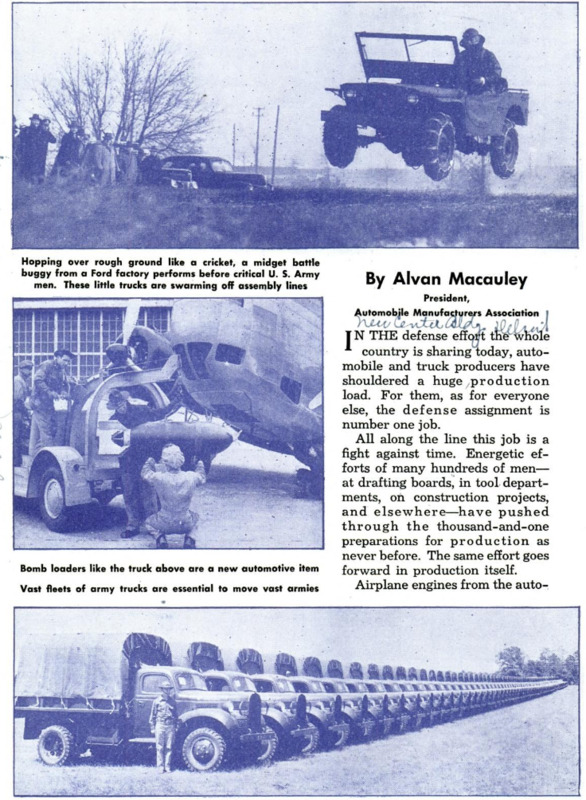

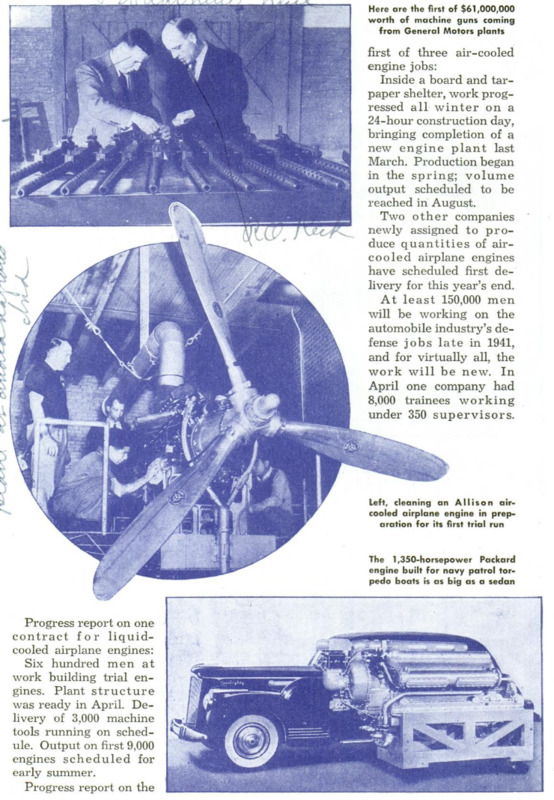

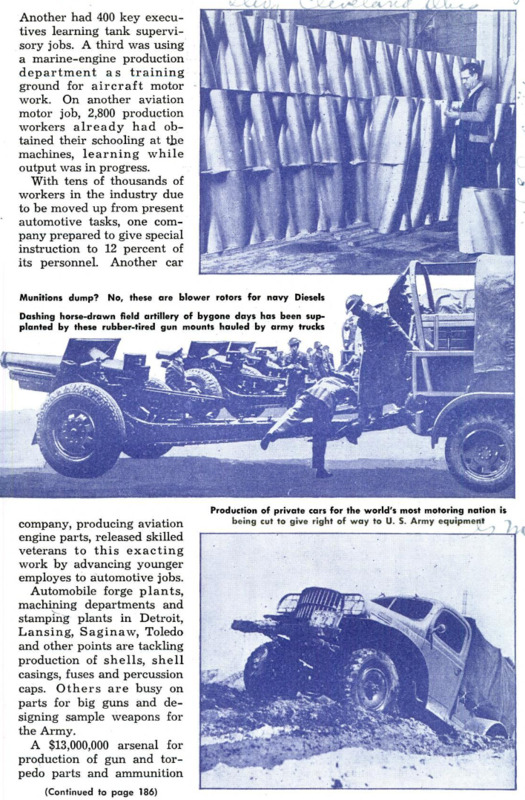

In the defense effort the whole country is sharing today, automobile and truck producers have shouldered a huge production load. For them, as for everyone else, the defense assignment is number one job. All along the line this job is a fight against time. Energetic efforts of many hundreds of men - at drafting boards, in tool departments, on construction projects, and elsewhere - have pushed through the thousand-and-one preparations for production as never before. The same effort goes forward in production itself. Airplane engines from the automobile industry went into service as early as July, 1940. The first of several factories was turning out 400 a month last April, with 1,000 a month to come, As other plants get into production, the automobile industry will be producing several times that number of airplane motors. In Detroit, Dearborn, South Bend, Chicago and Indianapolis, builders are working double and triple shifts to hurry the structures for added engine production. The machine tools required by the thousands for this specialized work - lathes, broaches, boring and drilling machines are being delivered on schedule. Progress report on one contract for liquid-cooled airplane engines: Six hundred men at work building trial engines. Plant structure was ready in April. Delivery of 3,000 machine tools running on schedule. Output on first 9,000 engines scheduled for early summer. Progress report on the first of three air-cooled engine jobs: Inside a board and tarpaper shelter, work progressed all winter on a 24-hour construction day, bringing completion of a new engine plant last March. Production began in the spring; volume output scheduled to be reached in August. Two other companies newly assigned to produce quantities of air-cooled airplane engines have scheduled first delivery for this year’s end. At least 150,000 men will be working on the automobile industry’s defense jobs late in 1941, and for virtually all, the work will be new. In April one company had 8,000 trainees working under 350 supervisors. Another had 400 key executives learning tank supervisory jobs. A third was using a marine-engine production department as training ground for aircraft motor work. On another aviation motor job, 2,800 production workers already had obtained their schooling at the machines, learning while output was in progress. With tens of thousands of workers in the industry due to be moved up from present automotive tasks, one company prepared to give special instruction to 12 percent of its personnel. Another car company, producing aviation engine parts, released skilled veterans to this exacting work by advancing younger employes to automotive jobs. Automobile forge plants, machining departments and stamping plants in Detroit, Lansing, Saginaw, Toledo and other points are tackling production of shells, shell casings, fuses and percussion caps. Others are busy on parts for big guns and designing sample weapons for the Army. A $13,000,000 arsenal for production of gun and torpedo parts and ammunition components for the Navy has been undertaken by one company with more than 4,000 men slated for jobs. Two plants are in production on machine guns, two more are far along in plans to get into production. A truck company is among several companies at work on artillery ammunition. Another manufacturer is converting a machine-gun design to U. S. standards. An automobile company has undertaken production of shell cases in a plant built for that purpose in World War days. Machines built especially for automobile forgings are ramming out shell blanks. Today’s equipment is capable of producing shells six times as fast as during the World War. Utilization of automotive forge tools was worked out through educational orders placed by the War Department early in 1940. These orders helped acquaint automobile men with defense production problems and paved the way for getting machining tools for finishing shells in volume, which no motor company possessed. Fast-moving fortresses, 28-ton medium tanks, are slated to roll out of a quartermile-long tank arsenal by early fall - ahead of schedule. The tanks to come will be built by production line methods. Totally unlike automobile and truck production is this job. The largest tank ring gear could circle the front end of a passenger car like a quoit around a stake. While the tank plant was still rising, pattern makers produced scale models in wood, exact to thousandths of an inch, to make possible prompt production of heavy armor plate units and the numerous intricate components of the tank shell and mechanism. As in automobile assembly these units have to be so exactly made as to be interchangeable. First shipments of sub-assembly units for airplanes from Detroit’s automotive plants, began in early February. ; Two programs are under way: Supply of units such as wing sections, flaps, tail surfaces, ailerons and other sub-assemblies to aid several airplane makers in completing contracts; second, a huge project under which automobile companies manufacture parts and sub-assemblies going into three of the newest types of bombing planes. Six manufacturers of motor vehicles and bodies are among the companies which have assignments in this work. From one to two hundred thousand men will be needed in fulfillment of these jobs. At the rate of 15 a week, marine engines from one automobile concern are going into navy torpedo boats. These 1,350-horse power engines dwarf even the largest automobile motors. It’s a navy secret how many Diesel engines are coming from one automobile plant for submarines and other naval craft. Almost the entire production of this plant has been converted to making propulsion machines for the U. S. fleet. Sharing the load of defense production, whether of motors, plane parts, tanks or vehicles, is a large and growing army of parts and accessory producers. Major automobile companies, too, have put their equipment to work on manufacture of precision units, crankshafts, connecting rods and other parts for aircraft engines. A truck maker turns out 8,000-pound transmissions for tanks. To increase the supply of magnesium, vital lightweight metal, a new foundry got into production during the winter. Aluminum casting capacity of the nation was stepped up 300,000 pounds a month by completion in 12 weeks of a new foundry built by another motor company. Through the Automotive Committee for Air Defense, which established a technical exhibit of aircraft parts in Detroit, the industry compiled an inventory of the facilities of 800 parts and accessory producers. This will speed distribution of orders among an expanding circle of plants, men and machines. Off the production lines of a score of automobile plants are rolling 13,000 army motor vehicles a month, a rate rising toward 20,000 monthly. In June the U. S. land forces expected to have 190,000 motor vehicles. The new cars form an assorted list - pygmy trucks 80 inches long, seven-ton jobs, armored reconnaissance and combat cars, field shops, hospital units and pesonnel carriers. Midget trucks are coming from three companies. Another is turning out strange looking units, half truck, half tractor. In between are four and six-wheel vehicles, from a half ton to seven tons capacity. Special military trailers, field range cabinets, field kitchens also are among the products of the automobile industry. Military trucks have special equipment - towing hooks for guns, blackout lighting equipment, radiator brush guards, high fenders and - most important - power transmitted to all wheels. Many carry armor plate. Army trucks travel 40, 50 miles an hour or more on roads. But they must also stand the punishment of operation across country - to get men, guns and supplies virtually anywhere that draft animals could take them, faster than any non-motorized column could travel. More than a quarter million vehicles of all types are expected to be in the army service by fall, with the truck assembly lines of the motor industry ready to produce as many more as defense needs might call for. Years of volume output for civilian service made it possible to meet quicly the high military requirements. There are many big defense jobs under way, and plenty of these involve painstaking, difficult work. Here is just one example which indicates how elaborate an accessory can be: The carburetor for a modern aircraft engine is more costly than many a complete automobile, more difficult to design than was the entire Liberty engine of World War days. The record of accomplishment to date is one of which the people of the country generally as well as those within the industry can feel proud.

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 2, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 2, 1941