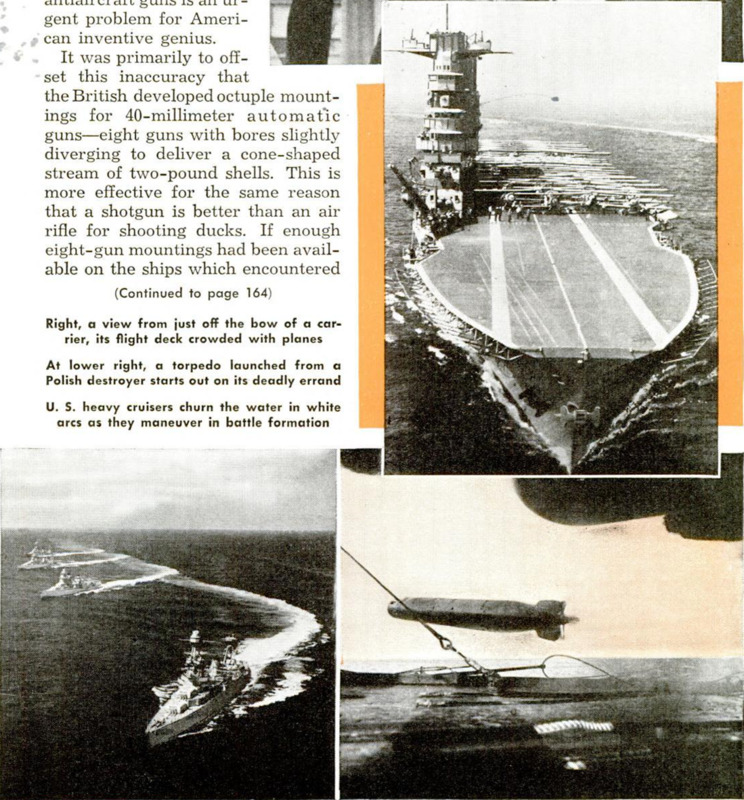

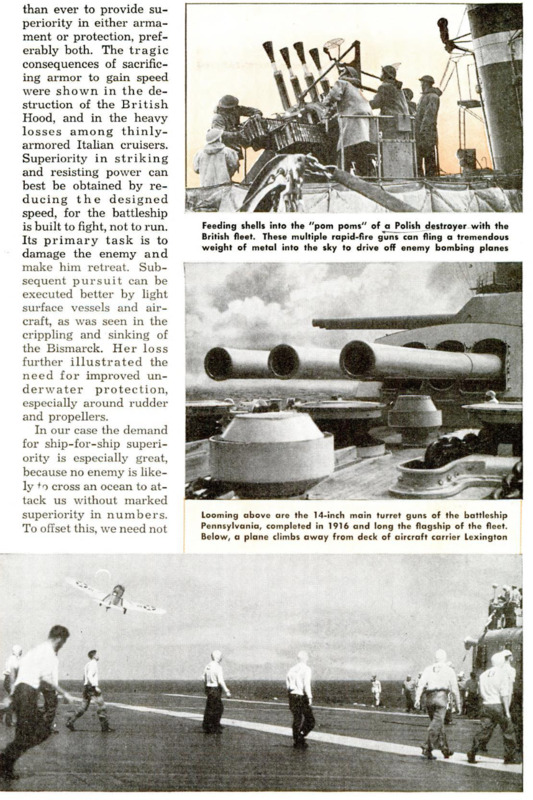

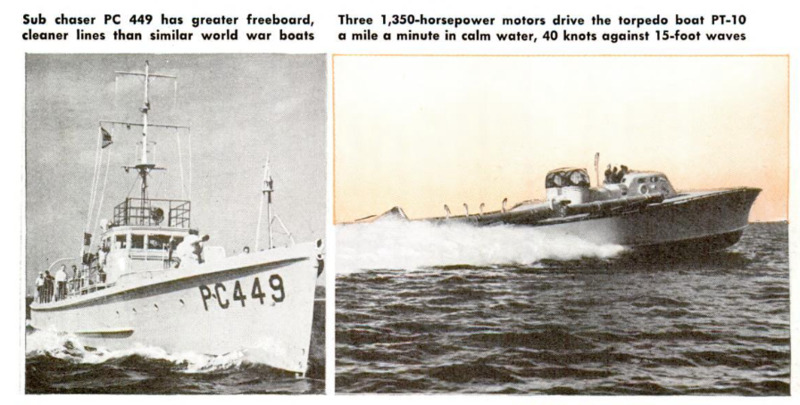

RACING against time to build a navy supreme over two oceans, the United States is learning lessons swiftly from the war in the Atlantic, the North Sea and the Mediterranean. For the first time naval observers have seen the ocean raider challenged by the aircraft carrier, the battleship challenged by the bomber, the plane itself challenged by the antiaircraft cruiser. Changing methods are multiplying the new forms of specialized craft. Navies are built for tomorrow, not for today, and America - with long seacoasts to defend and wide oceans to cover - must look far ahead to design her navy against the weapons of the future. Battleships must be bigger than ever to provide superiority in either armament or protection, preferably both. The tragic consequences of sacrificing armor to gain speed were shown in the destruction of the British Hood, and in the heavy losses among thinly-armored Italian cruisers. Superiority in striking and resisting power can best be obtained by reducing the designed speed, for the battleship is built to fight, not to run. Its primary task is to damage the enemy and make him retreat. Subsequent pursuit can be executed better by light surface vessels and aircraft, as was seen in the crippling and sinking of the Bismarck. Her loss further illustrated the need for improved underwater protection, especially around rudder and propellers. In our case the demand for ship-for-ship superiority is especially great, because no enemy is likely to cross an ocean to attack us without marked superiority in numbers. To offset this, we need not only units of greater striking and resisting power but also strategic bases from which light forces and aircraft can reinforce our fleet. In this respect our greatest need is for bases from which we could intercept any thrust from Africa to South America. Our battleships must also be tough enough to face the air fleets of 10 and 20 years hence, and so must carry perhaps double the antiaircraft guns and ten times the antiaireraft ammunition of present vessels to withstand a week-long attack by enemy planes. The outstanding innovation in naval design during this war has been the antiaircraft cruiser, a specialized ship whose every gun is an antiaircraft gun. Its major task is to defend merchant vessels and aircraft carriers against air attack. It can also be used for reinforcing destroyer flotillas or other especially vulnerable units. First vessels built from the keel up as antiair- craft cruisers are those of the British “Dido” class, 5,450-ton ships mounting ten 5.2-inch guns, sixteen 40-millimeter automatic guns in octuple mounts and two triple torpedo tubes. The 5.2-inch guns are formidable weapons against the high-altitude bomber, and especially effective for breaking up destroyer attacks. They might be slightly out-ranged by six-inch guns of a light cruiser, but the disadvantage is largely theoretical, for the brilliantly fought battle of smaller British cruisers against the Graf Spee showed how smoke screens can be used to compel an enemy to come to close quarters if he wishes to fight. Then, at close range, the higher rate of fire of the 5.2-inch guns more than offsets the lighter weight of their shells. No fire-control instruments, howeer, have yet been devised to overcome the difficulties of hitting so small and mobile a target as the airplane. Despite progress since the world war, a tremendous weight of metal is still thrown into the air for évery airplane destroyed. Ten planes are shot down by fighters for every one downed by antiaircraft guns. How to direct more accurately the tremendous fire of antiaircraft guns is an urgent problem for American inventive genius. It was primarily to offset this inaccuracy that the British developed octuple mountings for 40-millimeter automatic guns - eight guns with bores slightly diverging to deliver a cone-shaped stream of two-pound shells. This is more effective for the same reason that a shotgun is better than an air rifle for shooting ducks. If enough eight-gun mountings had been avail- able on the ships which encountered German dive bombers off Sicily and Crete, the British situation in the Mediterranean would be far more favorable. Furthermore, these multiple guns are the best weapon against torpedo boats. Our Navy has secured an appropriation to arm all our ships with plenty of multiple mounts for protection against torpedo planes, dive bombers and speedy surface craft. Although not new, the aircraft carrier is having its first effective use. The chief consequence of its use by the British is the relative scarcity of such commerce raiders as the Emden and Karlsruhe of world war fame. This is all the more remarkable since the Nazis, controlling the coastline from Norway to Spain, can send out raiders whenever they choose. Their difficulty is no longer in reaching the open sea - it is staying there; and what makes it dangerous to stay there is the aircraft carrier. Its planes search enormous areas in a day and concentrate an overwhelming force of planes on any enemy ship sighted, as the Bismarck discovered fatally. Consequently the Germans, aside from occasional forays in thick weather, use surface raiders only in remote areas where they have merely nuisance value. The aircraft carrier, however, has its own defense problem. Offering a big target from the air and easily vulnerable to submarihes, since it must steam in a straight line while planes land and take off, it needs an antiaircraft cruiser to ward off bombers and a screen of antisubmarine vessels. To protect convoys, Britain is building two types of craft, the escort vessel and the corvette. Both are practically unarmored and too slow for service with the fleet. Nevertheless, they have practically the same depth-charge equipment and listening gear as a destroyer; so are highly effective against submarines. A typical escort vessel is 250 feet long, displaces 1,200 tons, can make 19 knots, mounts eight 4-inch antiaircraft guns and a pom-pom. A typical corvette is 190 feet long, displaces about 500 tons, makes 17 knots and mounts only a single 4-inch gun and a pom-pom. The larger vessel has the advantage of a powerful antiaircraft battery and higher speed. The smaller vessel can be built more quickly and cheaply, costs less for upkeep, presents a smaller, more maneuverable target and requires a crew of only 50 men compared with 120 for an escort vessel and 150 for a destroyer. Another sensational innovation is the greatly improved motor torpedo boat. In the war of 1914-18 it was a fair-weather craft, and threw a bow wave so conspicuous as to render a surprise attack next to impossible. Today’s British speedboats are so light and highly powered that they skim over the water. Their two main engines are supplemented by a third small motor. This center engine can drive the boat at about nine knots, at which the bow wave is negligible and propeller noise so slight it cannot be picked up by enemy hydrophones. Thus the boat can creep up on one engine at night, fire its torpedoes and escape at full speed with main engines on. America is not slow to learn. Already, the Navy is massing a fleet of motor torpedo boats. Typical is the PT-10, powered with three 1,350-horsepower engines, capable of 52 knots or 60 miles an hour in smooth water and 40 knots against 15-foot waves. Specialized antisubmarine patrol craft are also being built, and it is understood the Navy budget plans 400 new escort and patrol vessels, sub chasers and mine sweepers. No battle fleet in dangerous waters is faster than its mine sweepers. Sending an American fleet into action requires much preparatory organization. It presupposes the readiness of a host of auxiliary vessels, tankers or handy bases for refueling, tugs and repair ships, hospital ships, seaplane tenders and many other specialized vessels. A surprise incursion into enemy waters may depend on taking advantage of fog or rain predicted by the Navy's long-range forecasters. Or the balance between victory and defeat may be weighed by ability of the naval air force to drive enemy planes out of the sky. American shipyards are turning out warcraft even faster than Navy schedules contemplated. The ships will be the best that American brains and skill can produce - and that best has always been good.