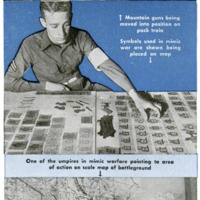

Tuning Up America's Defense Machine

Contenuto

- Titolo

- Tuning Up America's Defense Machine

- Article Title and/or Image Caption

- Tuning Up America's Defense Machine

- Lingua

- eng

- Copertura temporale

- World War II

- Data di rilascio

- 1941-10

- pagine

- 8-11, 192-193

- Diritti

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Sorgente

- Google books

- Referenzia

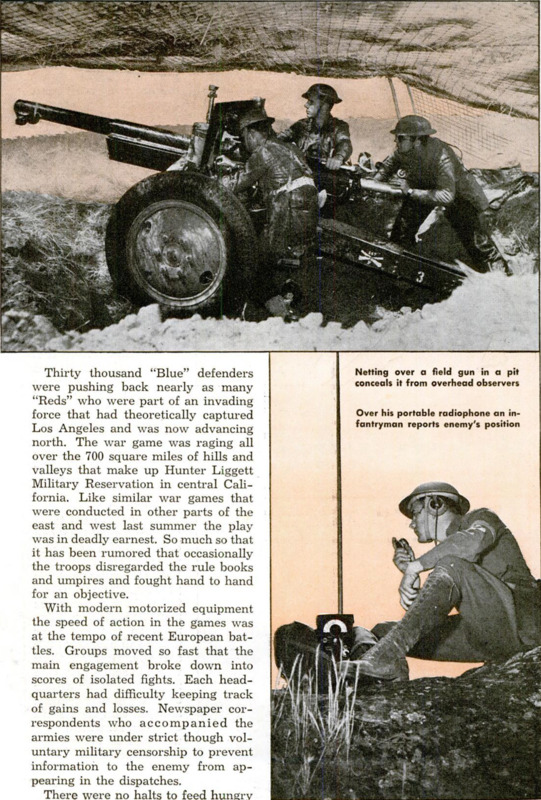

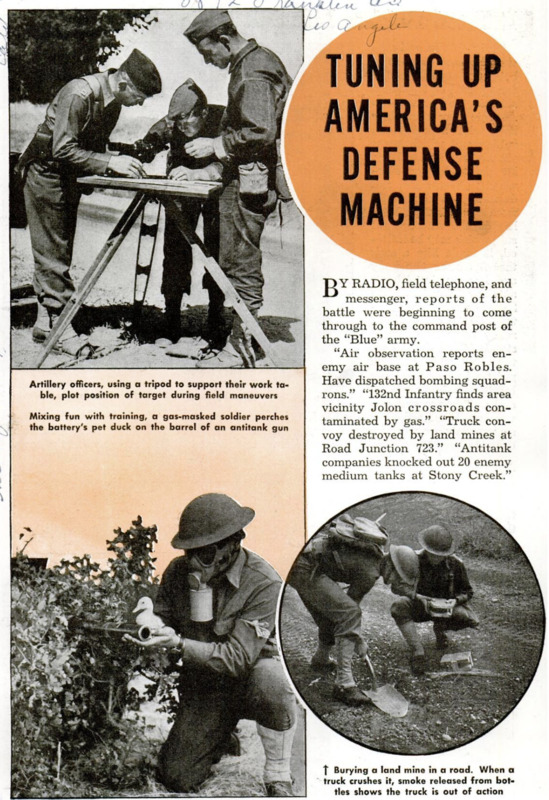

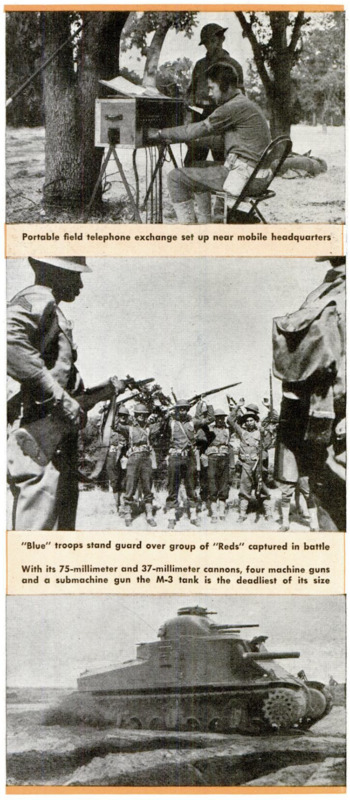

- Paso Robles

- Jolon

- Stony Creek

- Los Angeles

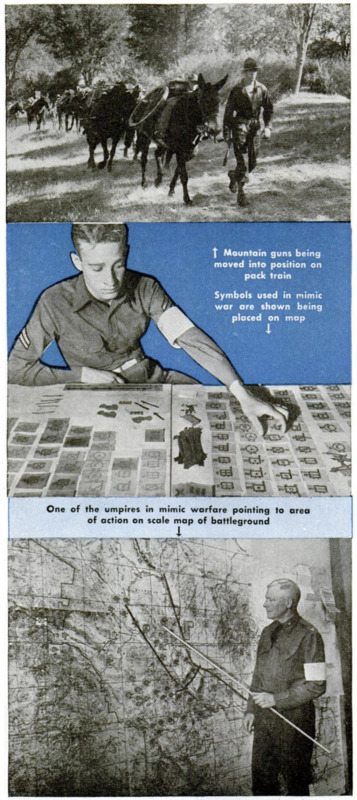

- Hunter Liggett

- California

- Europe

- Uncle Sam

- World War I

- Archived by

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

- Copertura territoriale

- United States of America