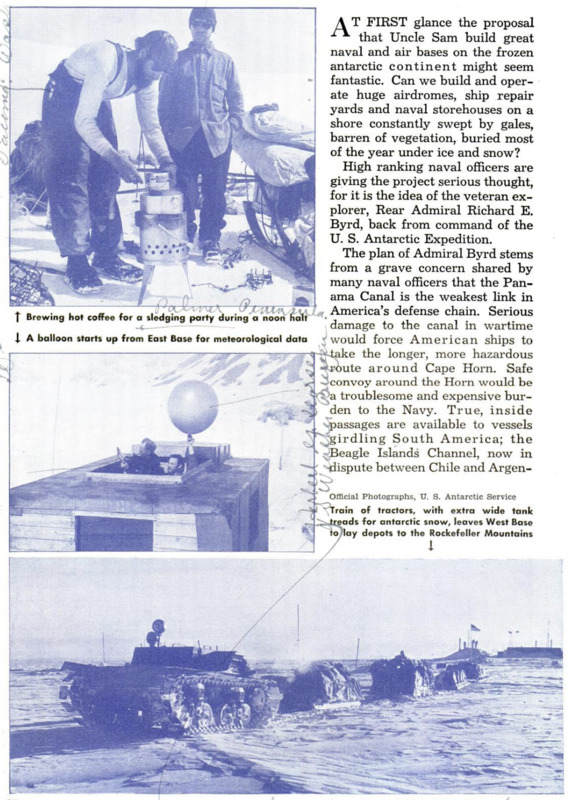

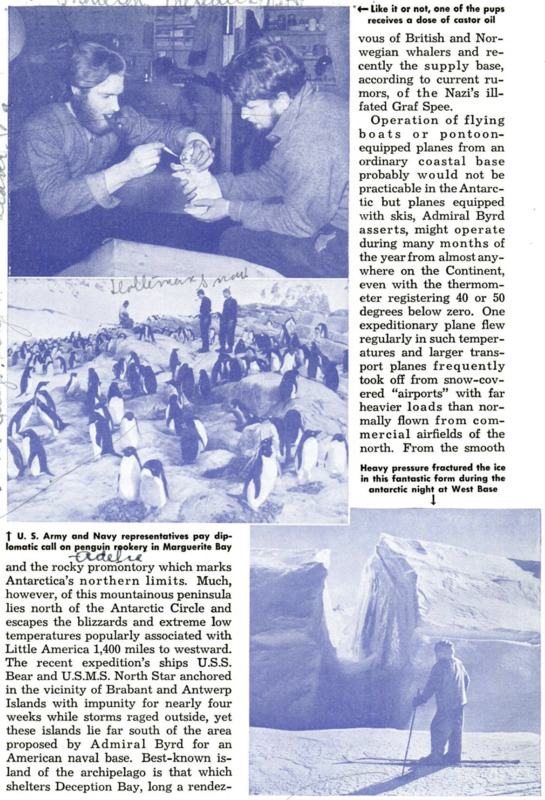

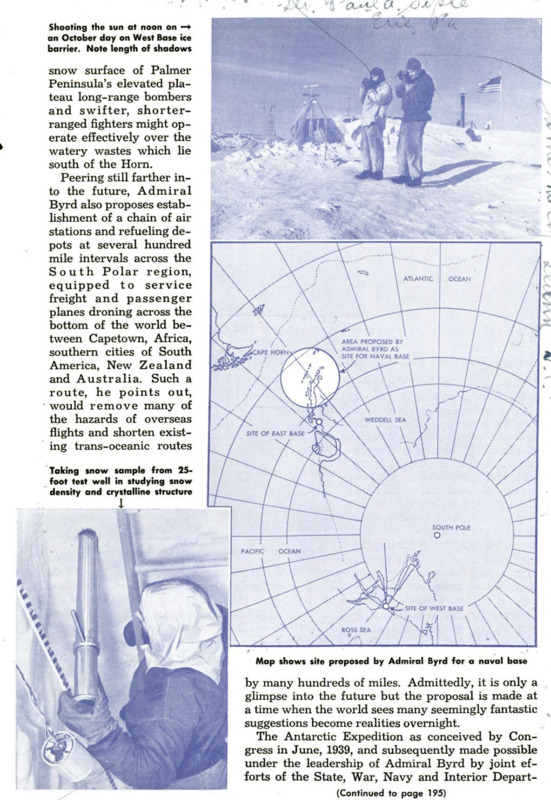

AT FIRST glance the proposal that Uncle Sam build great naval and air bases on the frozen antarctic continent might seem fantastic. Can we build and operate huge airdromes, ship repair yards and naval storehouses on a shore constantly swept by gales, barren of vegetation, buried most of the year under ice and snow? High ranking naval officers are giving the project serious thought, for it is the idea of the veteran explorer, Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd, back from command of the U. S. Antarctic Expedition. The plan of Admiral Byrd stems from a grave concern shared by many naval officers that the Panama Canal is the weakest link in America’s defense chain. Serious damage to the canal in wartime would force American ships to take the longer, more hazardous route around Cape Horn. Safe Sconvoy around the Horn would be troublesome and expensive burden to the Navy. True, inside passages are available to vessels girdling South America; the Beagle Islands Channel, now in dispute between Chile and Argentina, and the better-known Straits of Magellan are alternate routes, but their entrances would be tempting lurking places for enemy raiders. The third and only remaining route lies around Cape Horn, and to defend the waters between the Horn and Palmer Peninsula, northern extremity of the antarctic continent, naval bases at the bottom of the world would be essential. Only 400 miles of open sea lie between the grey-green cliffs of “El Cabo de Hornos” and the rocky promontory which marks Antarctica’s northern limits. Much, however, of this mountainous peninsula lies north of the Antarctic Circle and escapes the blizzards and extreme low temperatures popularly associated with Little America 1,400 miles to westward. The recent expedition’s ships U.S.S. Bear and U.S.M.S. North Star anchored in the vicinity of Brabant and Antwerp Islands with impunity for nearly four weeks while storms raged outside, yet these islands lie far south of the area proposed by Admiral Byrd for an American naval base. Best-known island of the archipelago is that which shelters Deception Bay, long a rendezvous of British and Norwegian whalers and recently the supply base, according to current rumors, of the Nazi’s ill-fated Graf Spee. Operation of flying boats or pontoon-equipped planes from an ordinary coastal base probably would not be practicable in the Antarctic but planes equipped with skis, Admiral Byrd asserts, might operate during many months of the year from almost any- where on the Continent, even with the thermometer registering 40 or 50 degrees below zero, One expeditionary plane flew regularly in such temperatures and larger transport planes frequently took off from snow-covered “airports” with far heavier loads than normally flown from commercial airfields of the north. From the smoothsnow surface of Palmer Peninsula’s elevated plateau long-range bomber and swifter, shorter-ranged fighters might operate effectively over the watery wastes which lie south of the Horn. Peering still farther into the future, Admiral Byrd also proposes establishment of a chain of air stations and refueling depots at several hundred mile intervals across the South Polar region, | equipped to service freight and passenger planes droning across the bottom of the world between Capetown, Africa, southern cities of South America, New Zealand and Australia. Such a route, he points out, would remove many of the hazards of overseas flights and shorten existing trans-oceanic routesby many hundreds of miles. Admittedly, it is only a glimpse into the future but the proposal is made at a time when the world sees many seemingly fantastic suggestions become realities overnight. The Antarctic Expedition as conceived by Congress in June, 1939, and subsequently made possible under the leadership of Admiral Byrd by joint efforts of the State, War, Navy and Interior Departments, did not entirely foresee the usefulness of such a venture to national defense. Like previous, privately-financed expeditions its personnel was concerned primarily with pushing back frontiers, probing the mysteries of Antarctica’s little-known interior, and following a scientific program which required painstaking observations and experiments in biology, meteorology, seismology, oceanography, bacteriology, geography and physiology. Government scientists were anxious to photograph Aurora Australis, the “Southern Lights,” with cameras widely separated but synchronized by radio; to transmit photographs halfway round the earth by radio and to study chemical changes in the human body during extreme climatic changes. As on previous expeditions, continuous observations also were to be made of fluctuating radio and magnetic waves. All this was accomplished, and in addition Admiral Byrd’s report to President Roosevelt tells of exploration by plane and dog sledge of more than 1,000,000 square miles of new or little-known territory; the mapping of 1,200 miles of new coastline; of his discovery of two great peninsulas jutting far into the southern Pacific, of seven new islands and many new mountain ranges whose rugged contours and prominent characteristics lend added weight to geographers’ long-standing suspicion that the great, ice-shrouded peaks of Antarctica are extensions of the Andes. These are spectacular achievements, and equally important discoveries in 20 branches of science only await completion of studies now being carried on by a dozen cartographers, physicists, biologists, geologists and terrestrial magnetists at various government agencies, scientific institutions and colleges. But while these scientists, still tanned and hardened from 15 months’ exposure to the rigors of antarctic life, are occupied with instruments and statistical reports, Uncle Sam is gaining a wealth of long-needed information of vital importance to the soldiers, sailors and marines now bolstering this nation’s defenses in Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and on lonely sea lanes of the north Atlantic, What sort of clothing best protects the body when the thermometer plummets to 50 degrees below zero? What is the best treatment for frostbite and snow blindness? Does the darkness of an arctic night rob the human body of essential vitamins? Do wounds and bodily injuries suffered in cold weather require different treatment from those received in temperate climates? These are only a few of the problems for which the Antarctic Expedition is providing answers daily to war-minded government bureaus. Cold weather clothing, always a serious problem to explorers in the past, was reduced to its lowest common denominator, expedition leaders have advised the War Department. Loose, well-fitting wool garments such as might be worn at home were found entirely adequate if supplemented with heavy wool parkas and outer garments of light, windproof material. Heavy furs were discarded except for plane flights and occasional use on the trail. Long-sleeved leather mitts containing wool “liners” kept hands warm at even 76.2 degrees below zero, while the best “mushing” boots were found to be ordinary garden-variety “arctics” with high felt boots inside. Because large ski boots played hobs with woolen socks, most men preferred snugger sizes which allowed only room for two pairs of heavy socks and a thin felt inner sole. Low temperature operation of tanks and tractors is of especial interest to the War Department and on that and related subjects the explorers brought back a wealth of information. Most tank treads are ineffective in deep snow but an Army tank driver and a Navy submarine engineer jointly devised a homemade contraption that enabled the heaviest tank at West Base to scamper around like a “Husky” puppy. Photos of the device were sent back by radio, another expedition experiment. Other devices included revolutionary radio equipment and exhaustive tests to determine the extent to which the Southern Lights and other electrical phe- nomena affected radio reception. Continuous records were also kept of cosmic ray and electron activities in high southern latitudes. Tests were even made on window glass of several types to determine which would remain transparent despite a temperature difference, inside and out, of 140 degrees. Under such conditions most windows would coat over quickly with Jack Frost patterns pleasing to children but scarcely to plane pilots flying at high altitudes. Members of the ice party also conquered the greatest bugaboo of all polar explorers - cold feet. Double floors with warm air circulating between solved the problem. Food is always important to armed forces, particularly in polar regions where the body consumes an abnormal amount of energy. A balanced diet, however, which included such delicacies as fresh fruits and vegetables packed in the States by modern freezing methods, and an ample supply of vitamin concentrates, kept the entire expedition in good health and spirits. More technical were the expedition’s experiments with preheated carburetion, condensation in gasoline lines, and relative efficiency of various antifreeze solutions. Each lesson learned was one step closer to successful operation of motorized United States forces in the far North. Surely, in ways undreamed of by earlier explorers, the recent Antarctic expedition yielded rich returns.