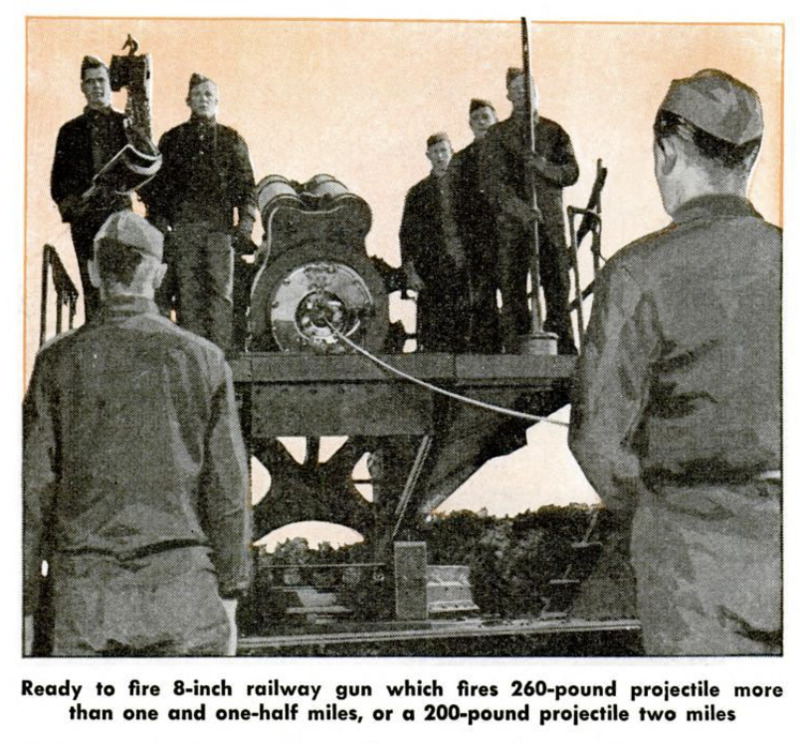

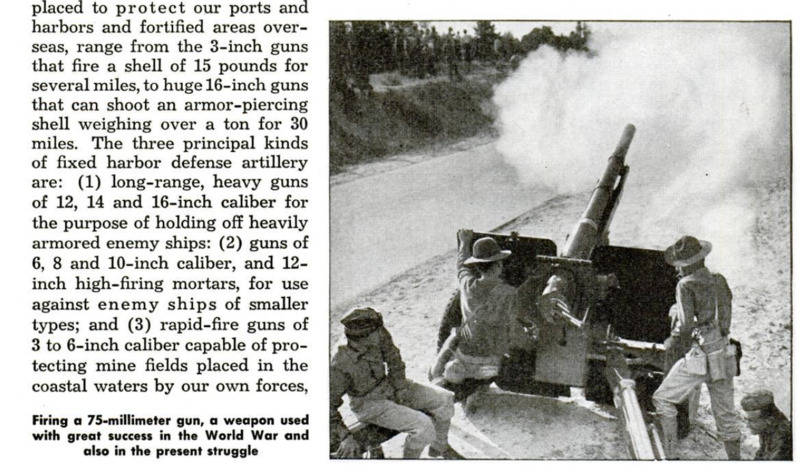

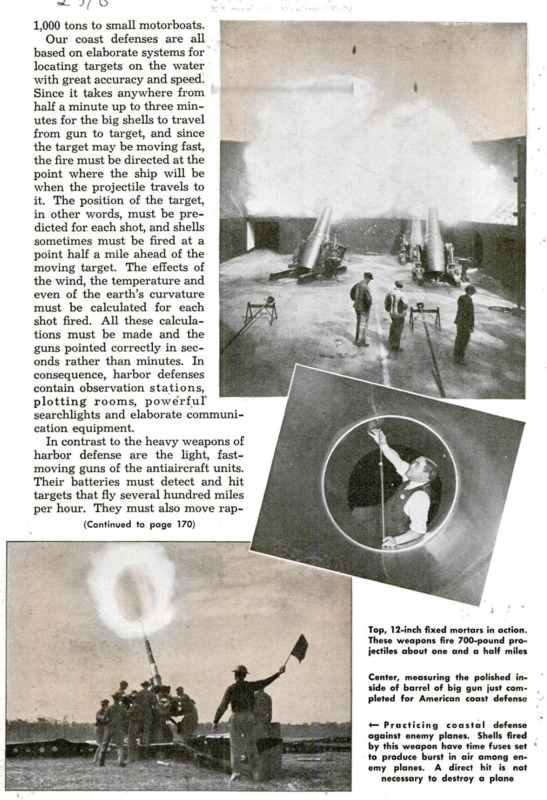

WHO ever heard of a “wall of steel” twenty-five miles thick? Probably not many people, but there is such a “wall” and it's of vital importance to the defense of our nation. Should circumstances be such that the U.S. Navy and the Army Air Forces were engaged elsewhere, an enemy approaching this country would be_cgnfronted by this wall while still 25 miles from shore. It would be composed of heayy projectiles from guns of the Coast Artillery Corps, the arm which occupies garrisons at strategic points around our domestic coast line, and at vulnerable points in our overseas possessions. With its fixed and mobile guns capable of firing one to 30 miles out to sea, the Coast Artillery Corps protects important parts of our shores - mainly the entrances to our largest harbors and ports, working in close cooperation with the U. S. Navy. In heavy artillery there is a trend toward mounting heavy guns in mobile carriages and aiming from fixed fortifications, but for protection of our seaport entrances the permanently emplaced gun is still of major importance. New developments in heavy artillery carriages have been built to increase both range and speed of the “Big Berthas.” A striking example is in the combined 155 mm gun 8-inch howitzer carriage upon which either can be mounted. Pneumatic tires and air brakes permit the gun to be towed behind high speed trucks. In firing position the carriage doesn't rest on the wheels, but is lowered to the ground by self-contained jacks. The range of this weapon is approximately 15 miles, which is 50 percent more than that of the somewhat similar type used in the World War. The Coast Artillery also has units with powerful antiaircraft guns whose purpose is to protect our most important centers of population and industry, and the main headquarters and installations of our armies in the field, from enemy war planes. Thus Coast Artillery regiments are of two main kinds – harbor defense and antiaircraft. Sometimes two or more regiments are formed into a brigade under one commander. Harbor defense regiments are of several kinds. Some are organized to man the big fixed guns in our coastal fortifications. Some operate the railway guns, also of larger calibers, which can be moved along the coast for any distance on railroads and set up for firing. Other regiments have guns that can be towed by fast, heavy trucks. All of these different regiments include within themselves antiaircraft units for their own protection. The Coast Artillery employs a variety of weapons. The guns of all calibers emplaced to protect our ports and placed to protect our ports and harbors and fortified areas overseas, range from the 3-inch guns that fire a shell of 15 pounds for several miles, to huge 16-inch guns that can shoot an armor-piercing shell weighing over a ton for 30 miles. The three principal kinds of fixed harbor defense artillery are: (1) long-range, heavy guns of 12, 14 and 16-inch caliber for the purpose of holding off heavily armored enemy ships: (2) guns of 6, 8 and 10-inch caliber, and 12-inch high-firing mortars, for use against enemy ships of smaller types; and (3) rapid-fire guns of 3 to 6-inch caliber capable of protecting mine fields placed in the coastal waters by our own forces, stopping fast enemy torpedo boats, and helping our troops to repel landings by enemy forces. Mobile railway and tractor or truck-drawn units are intended to defend our shores against landings attempted at points not protected by fixed defenses. The motor-drawn units are equipped with the 155-mm gun, which is practically the same as the field artillery gun of the same caliber. It can hurl a 95-pound projectile some 10 miles. Railway weapons include 8-inch guns, 12-inch mortars and 1d-inch guns. The 8-inch railway gun fires a 260-pound projectile whose maximum range is 28,000 yards, and can also use a 200-pound projectile with still greater range. The Coast Artillery also lays fields of electrically controlled submarine mines which can be exploded from shore as hostile ships pass over them, To install these mines in channels offshore, and to maintain them, the Coast Artillery uses boats ranging from ocean-going mine planters of over 1,000 tons to small motorboats. Our coast defenses are all based on elaborate systems for locating targets on the water with great accuracy and speed. Since it takes anywhere from half a minute up to three minutes for the big shells to travel from gun to target, and since the target may be moving fast, the fire must be directed at the point where the ship will be when the projectile travels to it. The position of the target, in other words, must be predicted for each shot, and shells sometimes must be fired at a point half a mile ahead of the moving target. The effects of the wind, the temperature and even of the earth’s curvature must be calculated for each shot fired. All these calculations must be made and the guns pointed correctly in seconds rather than minutes. In consequence, harbor defenses contain observation stations, plotting rooms, powerful searchlights and elaborate communication equipment. In contrast to the heavy weapons of harbor defense are the light, fast- moving guns of the antiaircraft units. Their batteries must detect and hit targets that fly several hundred miles per hour. They must also move rapidly to reach new firing positions in protecting moving troops. There are a few fixed antiaircraft guns at vital points, but all the rest are motorized and can move on highways - guns, searchlights, and all - at high speeds. Regiments of antiaircraft artillery are capable of traveling more than 300 miles in a single day. The present standard weapon of Coast Artillery antiaircraft units is tfle 5-inch antiaircraft gun, which fires a 13-pound projectile that is effective against enemy planes 4 miles up. The shells have time fuses set to burst in the air among the enemy’s airplanes. It is not necessary to make a direct hit on a hostile airplane to destroy it. In one minute a battery of four guns can fire 100 aimed shots. Each antiaircraft gun battery has a director, or “mechanical brain.” This complicated instrument, pointed continu- ously at an air target, automatically com- putes the right direction for pointing the guns and transmits it electrically to dials on each gun. The gun crew reads the dials and turns other dials to point the gun. Antiaircraft guns are supplemented by searchlights of approximately 800,000,000 candlepower which illuminate targets at night. To enable the searchlight crews to find the targets quickly as they approach high in the air over the guns, sound locators are used. These are really huge aids to hearing by which trained listeners can tell the direction from which the sound of approaching airplanes is coming, so that the searchlights can be pointed in that direction and can light up the targets accurately at the earliest possible moment. The searchlights, of course, are placed in a circle at a considerable distance from the gun batteries. Farther out are ground obserers who give advance warning to the whole antisircraft defense. To deal with low-flying enemy attack planes, our troops use the Browning caliber .50 machine gun and the 37-mm antiaircraft gun. The caliber .50 machine gun fires a stream of tracer bullets half an inch in diameter. The tracers burn with a bright light, so that the gunner’s eye can follow this stream of destructive fire power for nearly a mile. Each machine gun pours fire at aerial targets at a rate of several hundred rounds per minute. The 37-mm gun fires a small shell weighing about a pound at a rapid rate and is a powerful protection against hostile aircraft. The current European war has shown our military high command the need for a more powerful antiaircraft weapon; the Army has now begun production of a 90-mm gun. Also in development is a 4.7-inch weapon of longer range and more effectiveness even than the 90 mm. Automatic loading equipment is being developed for firing the 90 mm gun more rapidly.