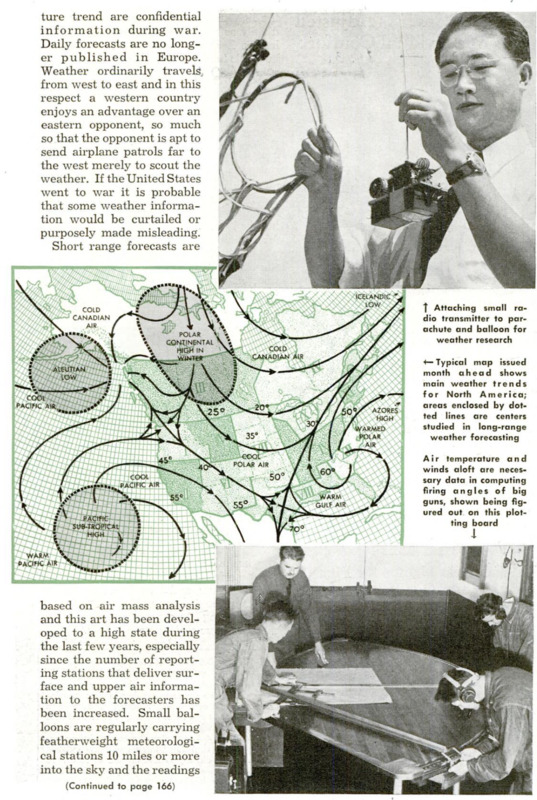

IN ANCIENT times, the leader of an army consulted an oracle to learn his chances of success; today an army commander planning a campaign, calls in a modern oracle - his chief meteorologist. “Major,” he says, “I want to know what weather we will be having 60 days from now. See if you can find me ten days in a row without any rain, sometime in October.” Ten rainless days would permit his mechanized forces to swarm across country at blitzkrieg speed. A rainstorm halfway through the drive might bog down his steel cavalry and quite likely turn the fight against him. History is full of accounts of battles in which the weather, rather than strategy or strength determined the winner. It seemed like sheer luck when the rains held off unseasonably and “General Mud” didnt arrive to slow down the German march through Poland. It seemed a coincidence when good weather also attended the invasion of Norway. But when campaign followed campaign, each fitting perfectly with the weather, experts concluded that Germany had found a way of foretelling the future and was taking advantage of it. That’s why, at the California Institute of Technology, among other universities, men from the Army, Navy, and Air Forces are absorbing new developments in military meteorology. Under Prof. Irving P. Krick, the Caltech students are learning weather secrets that may mean the difference between defeat and victory in war. The day has passed when a commander was forced to wish: “If the wind would only shift, we could launch a smoke screen and start a counterattack behind it.” Now he calls on the meteorology officer to tell him the exact hour when the wind will shift, and plans his attack accordingly. Bombers can't afford to leave the ground for a long raid until the weather officer instructs the pilots at what altitudes to fly to get fair winds and what the weather will be at the home base when they return. Big guns could fire all day without hitting their targets except for the upper air data that the weather office supplies. Every command post, air base, and fleet depends on its weather service predictions in planning its operations. Weather knowledge has become so important that its present state and future trend are confidential information during war. Daily forecasts are no longer published in Europe. Weather ordinarily travels, from west to east and in this respect a western country enjoys an advantage over an eastern opponent, so much so that the opponent is apt to send airplane patrols far to the west merely to scout the weather. If the United States went to war it is probable that some weather information would be curtailed or purposely made misleading. Short range forecasts are based on air mass analysis and this art has been developed to a high state during the last few years, especially since the number of reporting stations that deliver surface and upper air information to the forecasters has been increased. Small balloons are regularly carrying featherweight meteorological stations 10 miles or more into the sky and the readings of the instruments are automatically radioed back to earth. Because of the war, fewer ships at sea are sending in reports but those that do are supplying more information than in the past and are even reporting the direction and intensity of the swell. Long-range forecasting is just as vital in war as are the short-range predictions, but such forecasts haven't been used in the past because no one could make them accurately. During the last three years Professor Krick has been developing a system for foretelling the weather two and three months in advance, as well as giving a general picture of the climate for a whole season ahead. Krick’s predictions are based in part on the discovery that the key to future weather may be found in the movements of the so-called semipermanent “centers of action” which are persistent features in the atmospheric circulation. The Aleutian low, for instance, is a low pressure center that remains in the vicinity of the south Alaskan coast and that is characterized by strong winds and bad weather. The Pacific subtropical high, the polar continental high, the Icelandic low, and the Azores high are other centers of action. Longrange forecasting is based on studies of the size, shape, and movement of each center inside its area. Long-range forecasts, just as short-range weather predictions, are more of an art than an exact science because the accuracy of the predictions depends on the judgment of the forecaster which to a great extent is dependent on his experience. It seems odd that from a small office in Pasadena, Krick can foretell weather for points on the east coast as accurately as he can for local communities. He surveys the future for all parts of the United States and Canada. A month ahead of time he issues a long detailed bulletin to interested subscribers, parts of which are apt to read: “For March, rain and snow will be below normal in Montana, most of it occurring during the first few days of the month and between the 25th and 27th . . . rainfall in Texas will range from less than an inch in the southwest to two inches in the north- east, with temperatures above normal except for cold spells from the 5th to the 7th and from the 17th to the 19th . . . principal storms in New England between the 3rd and 5th and between the 28th and 30th....” Such forecasts, augmented with more specific information as the dates draw closer, help ice cream manufacturers to gauge their markets, allow knitting mills to estimate their production of sweaters or bathing suits, public utilities to judge the coming demand for power and fuel, and are even used by stock and bond owners to estimate the probable short-term earnings of companies whose earnings may be afected by the weather. Krick reports to water transportation companies in the east the probable dates when rivers will freeze up and when they will be free of ice again. One day he is apt to wire a Detroit electric company to expect heavy icing on overhead conductors tomorrow night and the same afternoon he may advise another electric company, in Mississippi, to expect numerous lightning strokes for two hours beginning at mid- night in the eastern part of its territory. Such advance information allows the concerns to prepare for the emergencies ahead of time and thus minimize the damage. Long-range predictions of the weather allow the commander of any army to lay general plans well in advance. Then the forecaster watches the weather trends from day to day and if he has to modify his predictions as the jump-off date draws near, preparations can be retarded or speeded up or the method of attack changed in time to conform to the new circumstances. Farfetched as it might seem at first, the long-range forecaster can even set the date for a battle half a year ahead of time. Sometimes fighting must be curtailed during the harvest season so that the men can gather the crops and a big general action must be postponed until the army is restored to full strength again. A close estimate of when that will be possible can be made the winter before, as soon as the forecaster obtains a close idea of the time and amount of the spring rains. These rains affect the size and maturing time of the crops and this information indicates the dates when they are to be harvested.