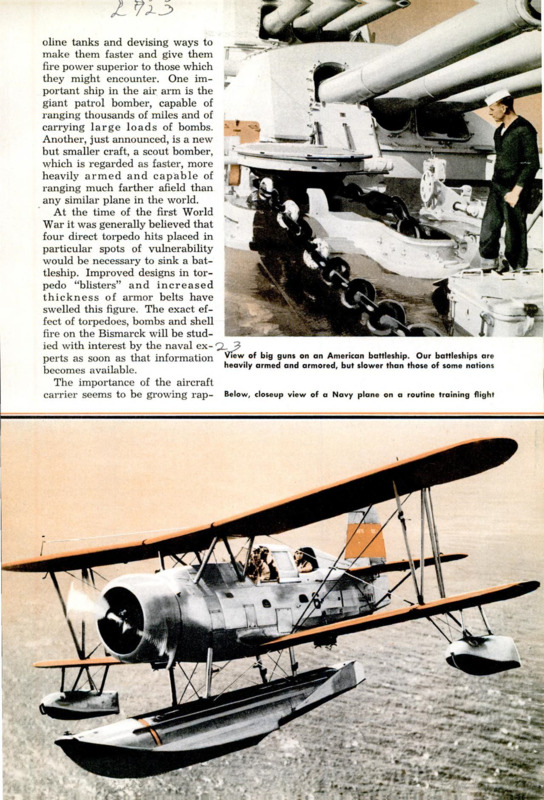

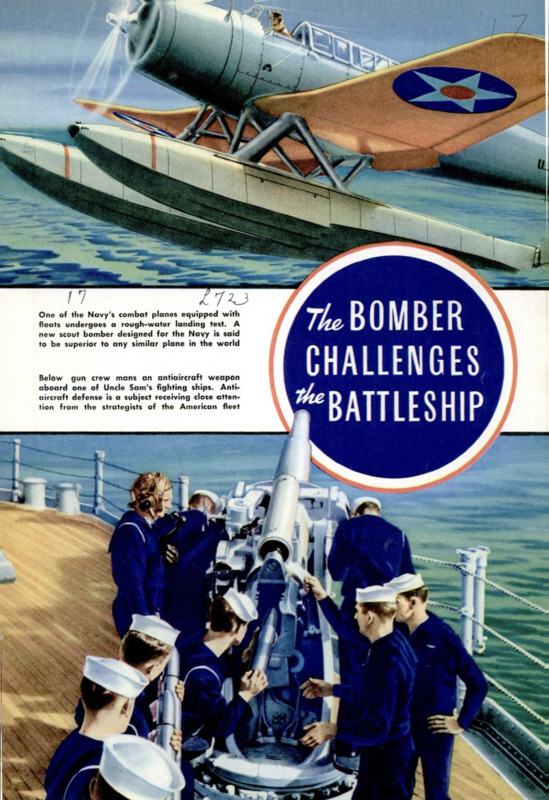

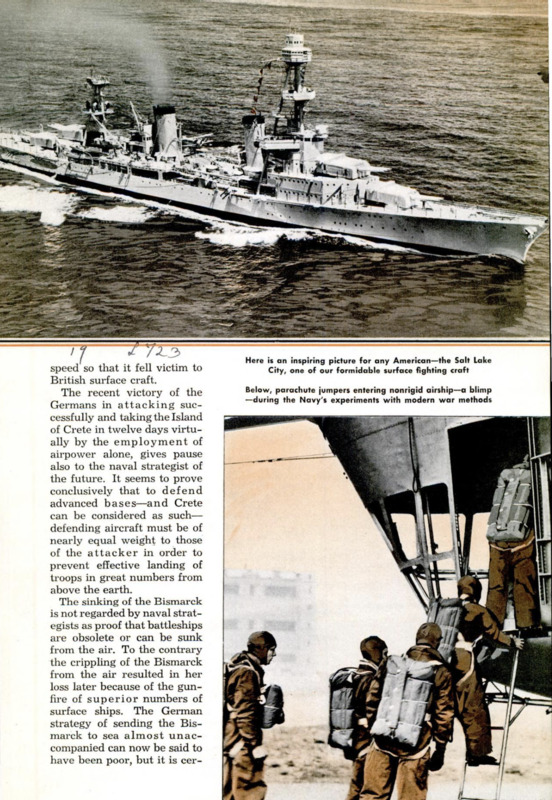

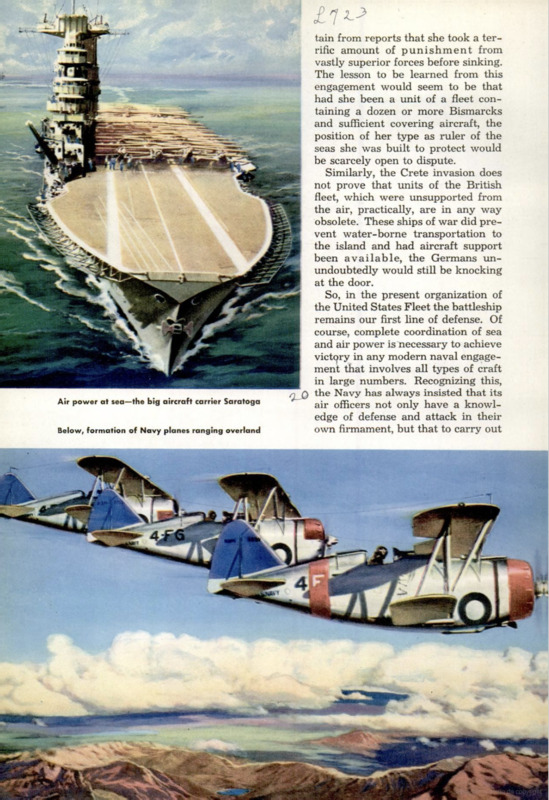

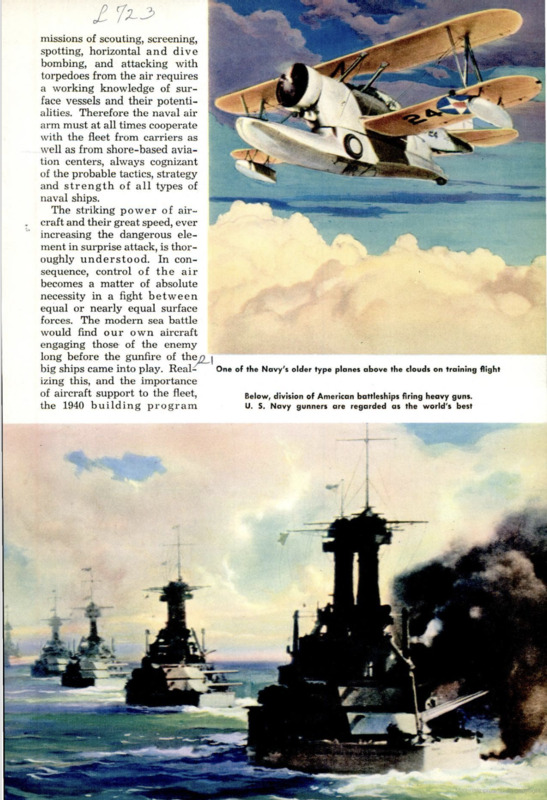

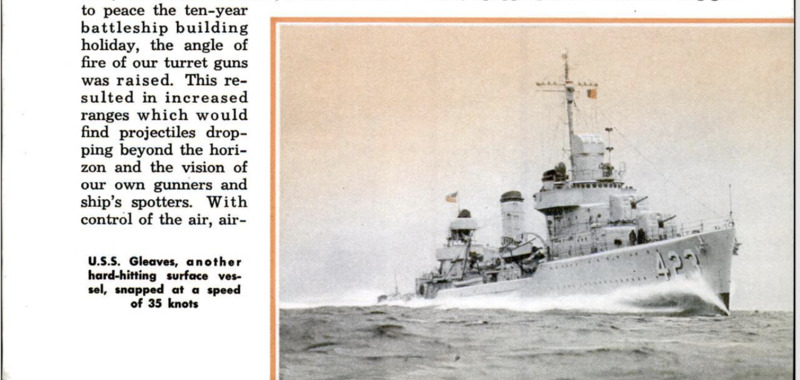

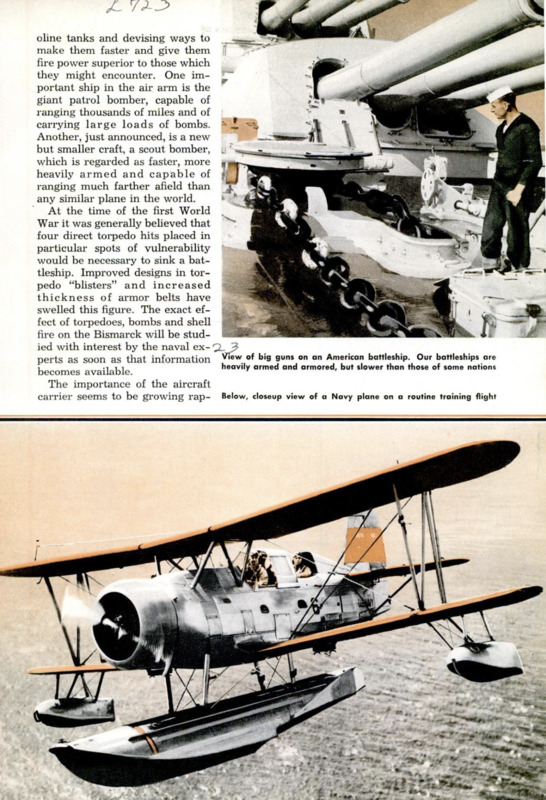

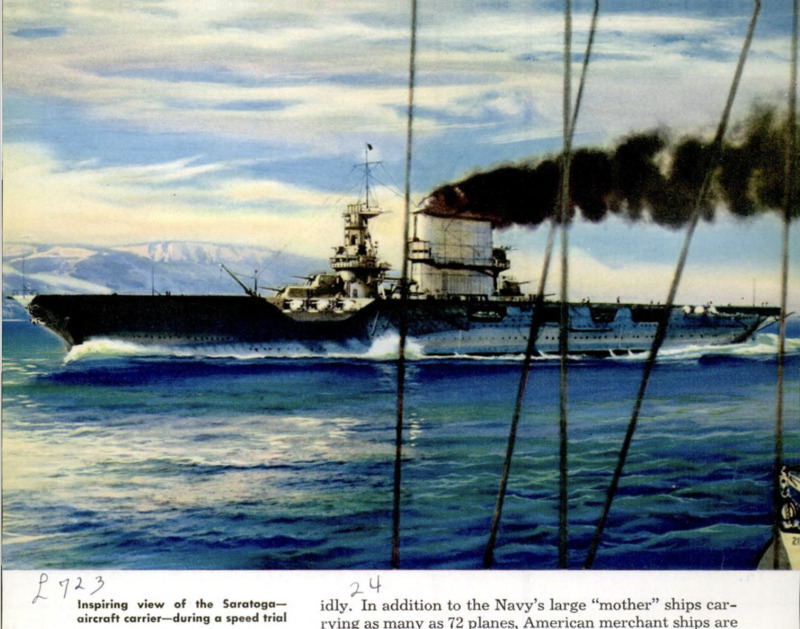

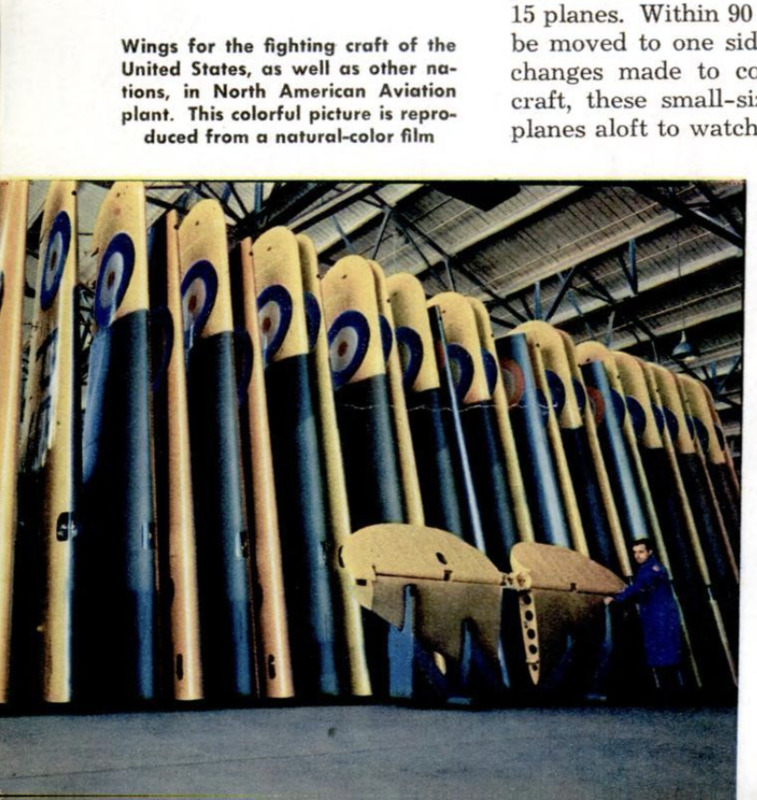

TREMENDOUS possibilities that lie within the airplane as a method of attack are not being overlooked by the United States Navy. Thus today our country’s defense program calls for 15000 combatant planes and a fleet capable of fighting in the Atlantic and Pacific at the same time against all combinations of enemies. That remarkable results have been achieved in the present conflict is recognized and our experts are studying these results. For instance, the torpedo plane, invented by our own Admiral Fiske, has been used to advantage, especially in closed harbors against Italian ships lying at anchor. Diving in and discharging their torpedoes before vessels could get under way or were even aware of their approach was a great accomplishment in crippling major elements of Mussolini’s fleet. Value of the airplane has been further emphasized by the part played by torpedo and bombing aircraft in the spectacular chase and sinking of the German battleship Bismarck, crippling the vessel and retarding itsspeed so that it fell victim to British surface craft. The recent victory of the Germans in attacking successfully and taking the Island of Crete in twelve days virtually by the employment of airpower alone, gives pause also to the naval strategist of the future. It seems to prove conclusively that to defend advanced bases - and Crete can be considered as such - defending aircraft must be of nearly equal weight to those of the attacker in order to prevent effective landing of troops in great numbers from above the earth. The sinking of the Bismarck is not regarded by naval strategists as proof that battleships are obsolete or can be sunk from the air. To the contrary the crippling of the Bismarck from the air resulted in her loss later because of the gunfire of superior numbers of surface ships. The German strategy of sending the Bismarck to sea almost unaccompanied can now be said to have been poor, but it is certain from reports that she took a terrific amount of punishment from vastly superior forces before sinking. The lesson to be learned from this engagement would seem to be that had she been a unit of a fleet containing a dozen or more Bismarcks and sufficient covering aircraft, the position of her type as ruler of the seas she was built to protect would be scarcely open to dispute. Similarly, the Crete invasion does not prove that units of the British fleet, which were unsupported from the air, practically, are in any way obsolete. These ships of war did prevent water-borne transportation to the island and had aircraft support been available, the Germans unundoubtedly would still be knocking at the door. So, in the present organization of the United States Fleet the battleship remains our first line of defense. Of course, complete coordination of sea and air power is necessary to achieve vietgry in any modern naval engage- ment that involves all types of craft in large numbers. Recognizing this, the Navy has always insisted that its air officers not only have a knowledge of defense and attack in their own firmament, but that to carry outmissions of scouting, screening, spotting, horizontal and dive bombing, and attacking with torpedoes from the air requires a working knowledge of surface vessels and their potentialities. Therefore the naval air arm must at all times cooperate with the fleet from carriers as well as from shore-based aviation centers, always cognizant of the probable tactics, strategy and strength of all types of naval ships. The striking power of aircraft and their great speed, ever increasing the dangerous element in surprise attack, is thoroughly understood. In consequence, control of the air becomes a matter of absolute necessity in a fight between equal or nearly equal surface forces. The modern sea battle would find our own aircraft engaging those of the enemy long before the gunfire of the big ships came into play. Realizing this, and the importance of aircraft support to the fleet, the 1940 building program called for more and better aircraft carriers, constructed in the ratio of two-to-one over other types of combatant vessels which were to double our navy in size and give us a two-ocean fleet. Control of the air as a precedent to surface action would allow our aircraft to harass the enemy. Torpedoes launched from planes, as well as destroyer squadrons, would attempt to force opposing battleships to turn from their course, throwing the big guns off their targets. It also would permit bombing and aircraft spotting of falling shells, the latter a development since World War No. 1. After the Washington Disarmament Conference of 1922, which had as its major contribution to peace the ten-year battleship building holiday, the angle of 3 fire of our turret guns was raised. This resulted in increased ranges which would find projectiles dropping beyond the horizon and the vision of our own gunners and ship’s spotters. With control of the air, aircraft spotters could judge the patterns of falling salvos and transmit to the ships of the fleet the proper changes in range and deflection to achieve direct hits. That the airplane does hold a challenge for surface vessels is fully acknowledged, so it has become expedient to protect American combatant ships above decks in order to resist better the effects caused by dive and horizontal bombing aircraft. Exposed equipment, such as fire-control instruments and range finders, aboard ship must be armored against splinters. Thicker upper and lower decks on major units must be so designed as to assure heavy bombs bursting outward and upward, rather than entering fire rooms, ammunition-handling rooms, magazines and oil compartments before exploding. Resistance to the bomber and the torpedo plane also demands rapid-firing antiaircraft guns, and plenty of them. Mounted in series, much as the British pom-pom has been used effectively in pouring metal into enemy planes, these guns can shake the attacking plane from its course and target. On the other hand, our strategists find it advisable to improve constantly our naval aircraft, armoring the planes against attack, equipping them with selfsealing gasoline tanks and devising ways to make them faster and give them fire power superior to those which they might encounter. One important ship in the air arm is the giant patrol bomber, capable of ranging thousands of miles and of carrying large loads of bombs. Another, just announced, is a new but smaller craft, a scout bomber, which is regarded as faster, more heavily armed and capable of ranging much farther afield than any similar plane in the world. At the time of the first World War it was generally believed that four direct torpedo hits placed in particular spots of vulnerability would be necessary to sink a battleship. Improved designs in torpedo “blisters” and increased thickness of armor belts have swelled this figure. The exact effect of torpedoes, bombs and shell fire on the Bismarck will be studied with interest by the naval experts as soon as that information becomes available. The importance of the aircraft carrier seems to be growing rapidly. In addition to the Navy's large “mother” ships carrying as many as 72 planes, American merchant ships are being converted into small-size carriers for escort or patrol work. These vessels are scheduled to carry about 15 planes. Within 90 days, a merchant ship’s funnels can be moved to one side, a flight deck installed and other changes made to complete the conversion. As patrol craft, these small-size carriers would be able to send planes aloft to watch for submarines and enemy surfaceships, covering a vast area of the ocean's surface. Once spotted by the patrol ship’s planes - scout bombers, for instance - the submarine would have difficulty in escaping because the aircraft could attack immediately or call in other planes to drop destructive bombs. To the oft-expressed opinion that air power is greater than sea power, Secretary of the Navy Knox says that this is no time to argue over the relative merits of one against the other, that it is a time to build more battleships, more planes, more submarines, cruisers and destroyers, that all factors of our defense be as powerful as possible. One lesson learned from engagements in the present struggle is that from the destruction of the British battle cruiser Hood, which was sunk in a few minutes by the Bismarck, prior to the sinking of the German battleship. Our experts say that this demonstrates the greater effectiveness of the latest battleships, with equal speed and increased armor, over battle cruisers built twenty or more years ago. Our naval constructors and engineers have always held out for the heavily armed, more ponderous battleship that can take it, as well as give, against superior speed with a sacrifice in armor. It is necessary, however, to have some major components of a fleet endowed with great speed, heavy gun power and less defensive equipment. Our newest cruisers will partly fill this requirement. Of course, speed has become a highly important factor in modern sea fighting. The ability of the Gneisenau and the Scharnhorst, German battle cruisers, to operate effectively against British convoys in the Atlantic, has been due to the fact that few ships of equal strength were able to catch them. In the air power against sea power argument, the battleship meets the challenge of the enemy bombing plane with heavier armor, antiaircraft guns and the fighting and bombing planes of its own fleet.