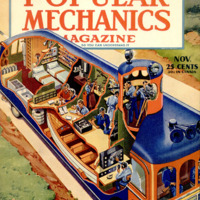

Testing the World's Biggest Bomber

Item

- Title (Dublin Core)

- Testing the World's Biggest Bomber

- Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

- Testing the World's Biggest Bomber

- Contributor (Dublin Core)

- Stanley Umstead (writer)

- Language (Dublin Core)

- eng

- Temporal Coverage (Dublin Core)

- World War II

- Date Issued (Dublin Core)

- 1941-11

- Is Part Of (Dublin Core)

-

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 5, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 5, 1941

- pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

- 28-31, 172-173

- Rights (Dublin Core)

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Source (Dublin Core)

- Google books

- References (Dublin Core)

- XB-19

- Archived by (Dublin Core)

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

- Spatial Coverage (Dublin Core)

- United States of America