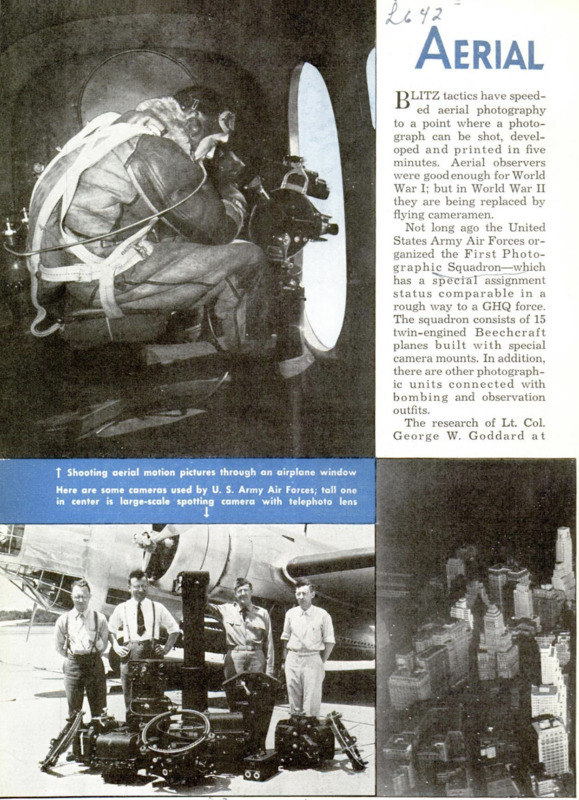

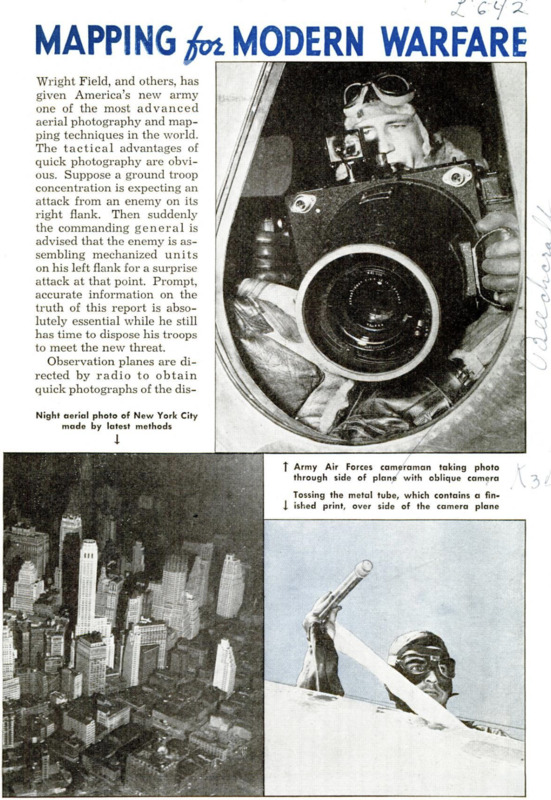

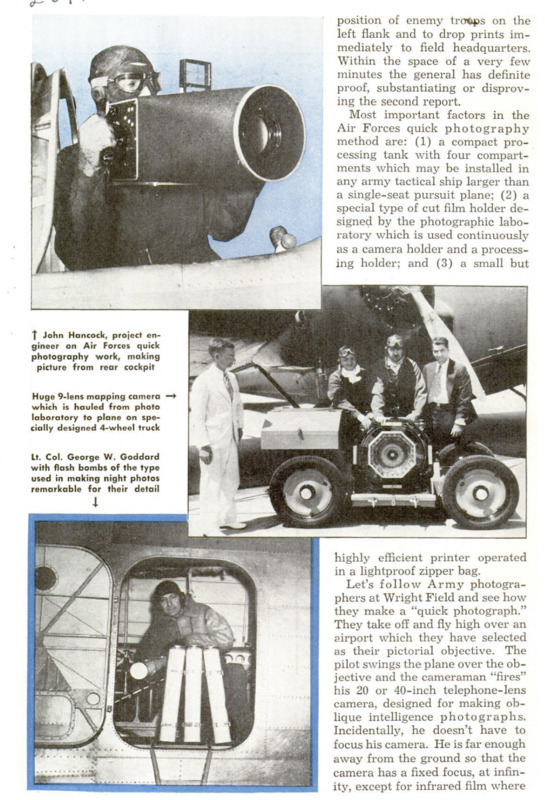

BLITZ tactics have speeded aerial photography to a point where a photograph can be shot, developed and printed in five minutes. Aerial observers were good enough for World War I; but in World War II they are being replaced by flying cameramen. Not long ago the United States Army Air Forces organized the First Photographie Squadron - which has a special assignment status comparable in a rough way to a GHQ force. The squadron consists of 15 twin-engined Beecheraft planes built with special camera mounts, In addition, there are other photographic units connected with bombing and observation outfits. The research of Lt. Col. George W. Goddard at Wright Field, and others, has given America’s new army one of the most advanced aerial photography and mapping techniques in the world. The tactical advantages of quick photography are obvious. Suppose a ground troop concentration is expecting an attack from an enemy on its right flank. Then suddenly the commanding general is advised that the enemy is assembling mechanized units on his left flank for a surprise attack at that point. Prompt, accurate information on the truth of this report is absolutely essential while he still has time to dispose his troops to meet the new threat. Observation planes are directed by radio to obtain quick photographs of the disposition of enemy troops on the left flank and to drop prints immediately to field headquarters. Within the space of a very few minutes the general has definite proof, substantiating or disproving the second report. Most important factors in the Air Forces quick photography method are: (1) a compact processing tank with four compartments which may be installed in any army tactical ship larger than a single-seat pursuit plane; (2) a special type of cut film holder designed by the photographic laboratory which is used continuously as a camera holder and a processing holder; and (3) a small but highly efficient printer operated in a lightproof zipper bag. Let's follow Army photographers at Wright Field and see how they make a “quick photograph.” They take off and fly high over an airport which they have selected as their pictorial objective. The pilot swings the plane over the objective and the cameraman “fires” his 20 or 40-inch telephone-lens camera, designed for making oblique intelligence photographs. Incidentally, he doesn’t have to focus his camera. He is far enough away from the ground so that the camera has a fixed focus, at infinity, except for infrared film where a special focus s required. All he has to worry about is exposure and lens opening. As soon as the exposure is made, he takes the holder from the camera and immerses it, in the first section of the tank. He pulls the slide up out of the holder so that it sticks above the tank and uses it as a handle to agitate the holder in the tank so that the negative is fully treated in the developer for one minute. Replacing the slide, he removes the holder and transfers it to the second section of the tank, where it gets the same agitating process for 15 seconds in a “stop bath” solution. The negative then gets 75 seconds in the third tank, a “fixing” solution, and a 5-second water rinse in the fourth tank. Incidentally, each section of the tank has a nonspill lid, so that the plane can do any ordinary maneuvers without spilling chemicals. The tank is jacketed in an insulation material one and one-half inches thick, which is electrically heated to a constant temperature of 75 degrees. After its rinse, the negative is quickly sponged off with a rubber squeegee, like those used by window washers, to remove extra moisture, and is then ready for printing. It is placed on the printer contact surface, and covered with a sheet of transparent material, to keep the printing paper from gelting wet. The sensitized paper is taken from a container and placed over the negative, and the lid is brought down to make the exposure. To the trained photographer there is nothing unusual about this procedure, but it must be remembered that the quick work photographer has his arms thrust into that black zipper bag, and is doing everything blindly - with his laboratory moving at 300 miles per hour. As soon as the print is exposed, the paper is placed in a holder similar to that used for the film, and is speeded through the same four processes of developing, stopping, fixing, and rinsing. It requires a total of two minutes, 35 seconds to process the film, 30 seconds more to squeegee it, and from 5 to 10 seconds for printing. Now it takes 20 seconds to develop the print, 20 seconds for stop bath, 15 seconds for fixing, and 5 seconds for rinse. The time totals 4 minutes and 15 seconds! Wright Field officials have clocked the complete process many times in under 5 minutes. The drying of the print is eliminated because the paper used is wax treated so that it sheds surplus moisture, and the print is immediately ready to be placed in a light metal tube container with sponge rubber shock absorbers, and dropped over the side. Quick photography, Army style, has been a subject of research ever since the days of the old McCook Field laboratories in Dayton in the early 1920's. The first quick photograph of unusual significance was made by Lt.-Col. Goddard and Cameraman Ben Thomas. It was a picture for President Coolidge, made at Dayton, from an airplane. And the plane followed the presidential train to nearby Xenia, where the finished print was dropped to the station and handed to the president. The present day speed of the process clearly indicates improved methods and equipment. The photographic laboratory has more tricks in its bag. A new type photographic paper holder is being experimentally produced, which will eliminate the need for the hood over the printer. The new holder will have the sensitized paper pasted in place, so that it can be laid on the contact surface, the top can be brought down, and then the slide can be pulled from the holder, making the exposure. As soon as the exposure is completed, and the paper is processed 1n the four tanks, holder and all can be dropped to the ground, with a streamer attached, thus making unnecessary the use of the tube container. The new holder will be of plastic, or some othermaterial that may be discarded without great loss, after a single use. In addition to providing quick prints to indicate the disposition of enemy troop concentrations, aerial photography plays many other important roles in warfare. Aerial mapping, for example, is rapidly replacing the slower and less accurate methods of ground mapping. We are accustomed to think that the United States is well surveyed, but Army experts declare that only 25 percent of this country is adequately mapped for military purposes. An industrial area like New York City, for example, changes so rapidly that old-style methods of mapping are far too slow. Aerial mapping is the answer to show where newly built roads, docks and airfields are located. Last winter the Army and the WPA broke all records in making an up-to-the-minute map of the New York area in several weeks - and at a cost of less than $65,000. Aerial photography is also useful in detecting enemy camouflage and in determining the adequacy of the Army’s own camouflage methods. Color photography and stereopticon examination of photographs reveal hidden details of terrain or troop movements that cannot be detected by the human eye. Use of infrared photography allows flying cameramen 1o shoot pictures on days when the ground is obscured by haze or light fog. Photographs have several important advantages over visual reconnaissance, Army experts point out. A photograph can be brought back to headquarters and studied at leisure by experts. A visual observer on the other hand, gets only a quick look at the ground from a speeding plane and is likely to miss many important details. Army experts also say that aerial photographs are helpful in checking the effect of their artillery fire and aircraft bombing. Enemy guns seldom waste ammunition to bring down a single, high-flying camera plane; yet another plane might draw fire of enemy antiaircraft guns if it swooped low enough for an observer to note the damage. The Army has done a good job in developing its aerial photography and mapping techniques. It is finding that the old Chinese proverb has a modern application: “One picture is worth 10,000 words.”

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 5, 1941

Popular Mechanics, v. 76, n. 5, 1941