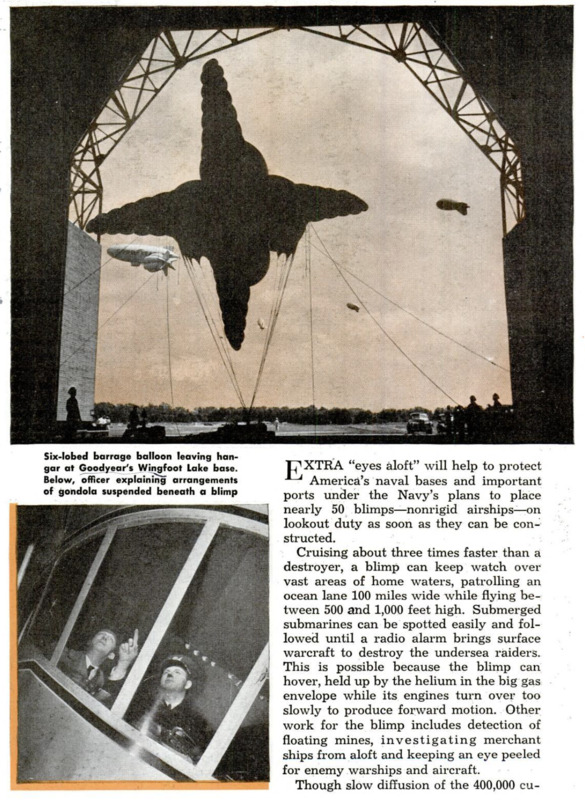

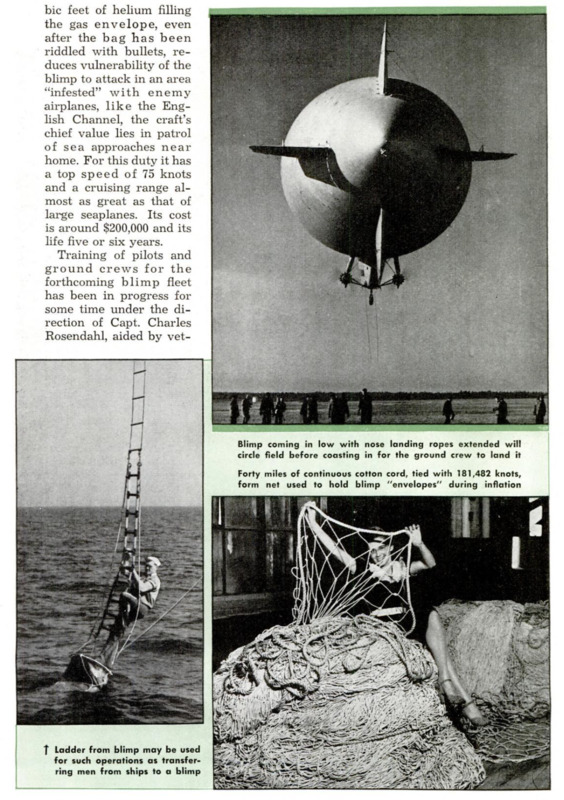

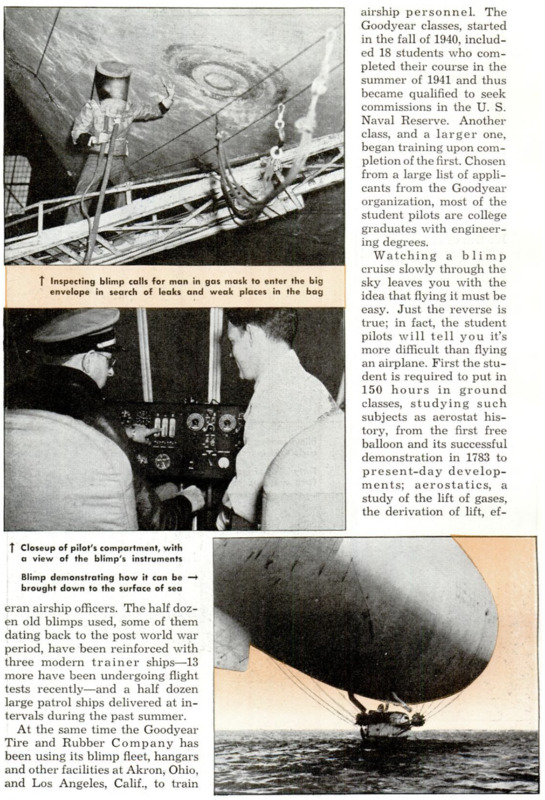

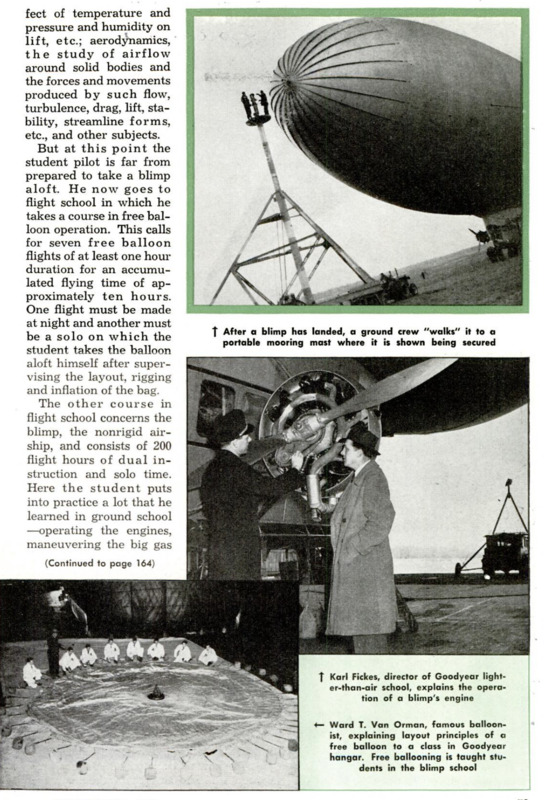

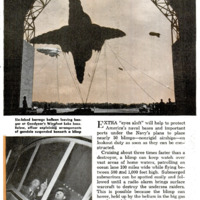

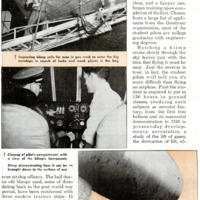

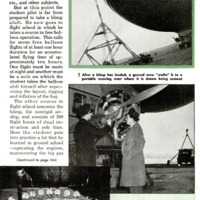

EXTRA “eyes aloft” will help to protect America’s naval bases and important ports under the Navy's plans to place nearly 50 blimps - nonrigid airships - on lookout duty as soon as they can be constructed. Cruising about three times faster than a destroyer, a blimp can keep watch over vast areas of home waters, patrolling an ocean lane 100 miles wide while flying between 500 and 1,000 feet high. Submerged submarines can be spotted easily and followed until a radio alarm brings surface warcraft to destroy the undersea raiders. This is possible because the blimp can hover, held up by the helium in the big gas envelope while its engines turn over too slowly to produce forward motion. Other work for the blimp includes detection of floating mines, investigating merchant ships from aloft and keeping an eye peeled for enemy warships and aircraft. Though slow diffusion of the 400,000 cubic feet of helium filling the gas envelope, even after the bag has been riddled with bullets, reduces vulnerability of the blimp to attack in an area “infested” with enemy airplanes, like the English Channel, the craft’s chief value lies in patrol of sea approaches near home. For this duty it has a top speed of 75 knots and a cruising range almost as great as that of large seaplanes. Its cost is around $200,000 and its life five or six years. Training of pilots and ground crews for the forthcoming blimp fleet has been in progress for some time under the direction of Capt. Charles Rosendahl, aided by veteran airship officers. The half dozen old blimps used, some of them dating back to the post world war period, have been reinforced with three modern trainer ships – 13 more have been undergoing flight tests recently - and a half dozen large patrol ships delivered at intervals during the past summer. At the same time the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company has been using its blimp fleet, hangars and other facilities at Akron, Ohio, and Los Angeles, Calif, to train airship personnel. The Goodyear classes, started in the fall of 1940, included 18 students who completed their course in the summer of 1941 and thus became qualified to seek commissions in the U. S. Naval Reserve. Another class, and a larger one, began training upon completion of the first. Chosen from a large list of applicants from the Goodyear organization, most of the student pilots are college graduates with engineering degrees. Watching a blimp cruise slowly through the sky leaves you with the idea that flying it must be easy. Just the reverse is true; in fact, the student pilots will tell you it's more difficult than flying an airplane. First the student is required to put in 150 hours in ground classes, studying such subjects as aerostat history, from the first free balloon and its successful demonstration in 1783 to present-day developments; aerostatics, a study of the lift of gases, the derivation of lift, effect of temperature and pressure and humidity on lift, ete; aerodynamics, the study of airflow around solid bodies and the forces and movements produced by such flow, turbulence, drag, lift, stability, streamline forms, etc,, and other subjects. But at this point the student pilot is far from prepared to take a blimp aloft. He now goes to flight school in which he takes a course in free balloon operation. This calls for seven free balloon flights of at least one hour duration for an accumulated flying time of approximately ten hours. One flight must be made at night and another must be a solo on which the student takes the balloon aloft himself after supervising the layout, rigging and inflation of the bag. The other course in flight school concerns the blimp, the nonrigid airship, and consists of 200 flight hours of dual instruction and solo time. Here the student puts into practice a lot that he learned in ground school - operating the engines, maneuvering the big gas bag with its gondola suspended beneath in various kinds of weather, mooring to permanent masts or to one attached to a tractor, and all the other fine points of flying a blimp. Director of the Goodyear training course is Karl L. Fickes and one member of the ground school faculty is Ward T. Van Orman, internationally famous free balloonist. Among the newer developments worked out by the U. S. Navy is a method for taking on water ballast at sea. As the blimp grows lighter through consumption of fuel, the pilot swings down within 100 to 150 feet of the water and lowers a hose. At the extreme end of the hose is a small scoop made of metal. It is three inches long and only an inch wider than the hose itself, to lessen drag. Twenty-five feet up from the scoop is the “fish,” a streamline cylinder shaped like a blimp and carrying an electric pump inside. The “fish” is 22 inches long, eight inches in diameter and has tail fins to keep it from spinning in the water. The “fish” skims along the water or jumps out like a porpoise, but the scoop is heavy enough to trail beneath the surface and stay directly in the ship’s wake. Thus the blimp can pick up water at cruising speed in a few minutes, no matter whether the surface is rough or smooth. Taking on fuel is accomplished in a novel manner. Informed by radio that the ship approached can spare some gasoline, the blimp pilot drops on the ship’s deck two rubberized fabric spheres connected by 14 feet of rope. One sphere, the smaller, is an air-filled buoy, the larger, about three feet in diameter when filled, is the fuel bag. The surface ship fills the fuel bag, then drops both bags overboard. The airship flies over the bags, drops a hook between them and retrieves the bags, then pumps the gasoline into the blimp's tanks. Sick or wounded men can be rescued - taken off surface craft - by means of special gear that also may be employed for picking up supplies or transferring crew members at sea. A cone-shaped rubberized fabric bag, ten feet long with a diameter of 214 feet at the top, is lowered 50 feet below the airship by cables, two in number, with rungs across them to form a ladder. Half of the cables consist of heavy extension cord to dampen the effect of wave movements. On top of the cone is a wire mesh cover which allows the water to pass through and which is strong enough to act as a platform, supporting the man. As the cone is filled with water, the airship drops enough ballast so that the “mooring mast” is only half submerged, making for stability even in a high sea. The airship then may either shut off the engines, or remain under way with engines running slowly. The surface ship sends a small boat alongside and the transfer of crew members or supplies up and down the ladder, or by winch, can be effected. In the same manner a sick passenger may be picked up and hurried ashore. When the blimp is ready to leave its anchorage, the cone is tripped, spilling the water and the crew hauls the gear up by a line attached to the bottom of the cone. If a blimp wishes to remain in a certain area without using fuel, either to employ its listening devices against submarines or to make repairs, it drops a newly devised sea anchor. This consists of a flat metal disk, or a steel ring with a fabric center, which is dropped into the ocean at the end of 200 feet of cable, with a small buoy to keep it afloat, and a weight below to hold it several feet below the surface. The cable is attached to the disk by a three-point bridle to get correct down pull and to facilitate lifting the anchor when desired. Landing on the sea - in calm water, of: course – is possible when flotation gear is attached to the car, or gondola, or when the car is built watertight. The car floats on the surface with some anchoring device holding the blimp. With the aid of these devices, a blimp could go out with the fleet for a month, perhaps several months, picking up ballast and fuel once or twice a day and changing crews every 24 hours. Thus it might be employed for reconnaissance, convoy work or as a listening post. Even alone, a military airship might operate away from its base for months at a time if need be, picking up fuel and supplies from surface ships, while it kept watch for enemy craft approaching America’s shores.