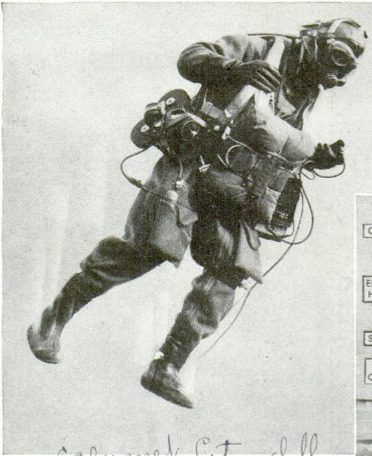

Radio Reports Chutist's Pulse in Six-Mile Fall

Contenuto

- Titolo

- Radio Reports Chutist's Pulse in Six-Mile Fall

- Article Title and/or Image Caption

- Radio Reports Chutist's Pulse in Six-Mile Fall

- Lingua

- eng

- Copertura temporale

- World War II

- Data di rilascio

- 1942-01

- pagine

- 6-7

- Diritti

- Public Domain (Google digitized)

- Sorgente

- Google books

- Referenzia

- Chicago

- Archived by

- Enrico Saonara

- Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)