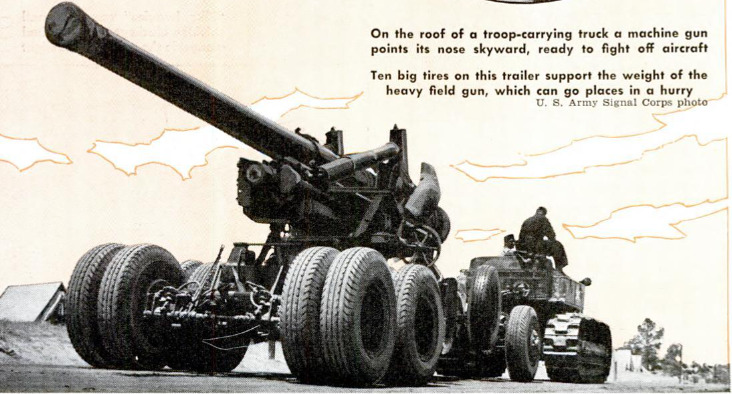

DOG-TIRED aiter 48 hours in the field under battle conditions, the 15th Infantry, U. S. A, didn’t expect an “alert” when it returned to camp in central California. But emergency orders were there. “2nd Battalion, prepare to leave Initial Point at 8 p.m.,, reach March Field at 8 am.; 1st Battalion, prepare to leave Initial Point at 9 p.m.,, reach Ventura at 6 am.; 3rd Battalion in reserve.” Two thousand men with their full field equipment, tentage, machine guns, antitank guns and mortars, extra ammunition and rations, and military baggage down to the last typewriter, had three hours notice to prepare to move 250 miles overnight. Already the plans-and-training officer was preparing the written orders, route maps, and march tables. Reconnaissance parties had started south and extra troop carriers were being dispatched from other regiments. March unit commanders synchronized their watches. At eight o'clock the first serial of 100 trucks, splitinto three march units spaced five minutes apart, was moving out onto the highway. Road speed was 25 miles per hour. With a 50 yard interval between vehicles, the column was five miles long. The drivers used their headlights, not the shuttered blue “black-out” beams that they would switch on in a real emergency. Individually, the drivers could travel at twice the ordered speed but the moderate rate was fast enough to cover ground-and still allow civilian traffic to flow past safely. Going through towns, each march unit closed up, almost bumper to bumper, and was convoyed through traffic by civil police that the reconnaissance parties had warned. On hills and curves the column lengthened out because of the different gear ratios and acceleration rates of the various types of four and six-wheel-drive vehicles. Little 500-pound “blitz buggies” can climb hills faster than the big personnel carriers loaded with 20 men, and a command car has more reserve power than one of the service trucks with its load of spare parts or repair equipment. Ten years ago, for such a trip, the soldiers would have had to wait until train schedules could be revised and a troop train made up, or they would have had to hike the distance at 15 or 20 miles a day. Motorized, they go where they are needed, on their own schedule. Trains are faster but more vulnerable to damage than are trucks that have the choice of several routes and can move around destroyed areas. The modern streamlined infantry regiment is not entirely motorized nor at the moment is it ever expected to be. The some 200 vehicles attached to a regiment are for scouting, hauling ammunition and baggage, for use as ambulances, and for other special purposes. The bulk of the men march on foot. But in an emergency the entire regiment marches on wheels, in big 1 1/2 and 2 1/2-ton trucks. The 1 1/2 ton kitchen trucks and trailers are spaced in the centers of the march units and the cooks prepare meals while the column is moving. A regiment can halt, eat, and be on its way again in half an hour. Drivers spell each other at two-hour intervals. There are periodic halts to inspect the motor equipment and to rest the men. In bad weather the big personnel carriers are halted until canvas tops and sides can be unrolled. The trucks can go more than 200 miles on a tank of gas and each vehicle also carries extra fuel to be placed in the tank at the noon halt. One of the duties of the reconnaissance party that precedes the column is to pick out the camp site where the motorized outfit will spend the night and to arrange for several fuel tank trucks to be on hand. The army trucks gas up, check water, air, and oil, and are prepared for the road again before they are parked for the night. If danger from aircraft is being simulated the trucks are camouflaged and parked under trees, or if the camp is in open country the trucks are scattered over a wide area. The flow of ordinary traffic plus road conditions sometimes tend to disrupt schedules but the job of each column is to reach its destination on time, as a unit. Control points are established on the route maps and the march units are checkedoff as they pass these points. Vehicles that have engine or tire trouble fall out and catch up with the tail of the unit after repairs are made. Guards are posted at railroad crossings. Guides are stationed at important turn-off points. Each guide wears a blackboard across his chest, on which he chalks the time that the tail of the last march unit passed his post so that the leader of the following unit will know whether to speed up or slow down to maintain his five-minute interval. From his command car the leader of the serial maintains close control of his column by motoreycle messengers, radio, and by observation planes. Messages may be dropped off at the guide posts to be delivered to the march units behind. On extended trips that may require several days, an airplane is used to check over the miles of vehicles, spotting the head and tail of each march unit by the white stripes on the tops of the leading and rear trucks, and reporting the positions to the serial commander by radio. The portable ‘“walkie~talkie” radio is used also for communication with one of the command cars which is fitted out as a mobile radio station. The brunt of modern fighting is borne by mechanized equipment. Tanks, as well as troop carriers and guns of all sizes mounted on rubber-tired wheels, can maneuver across rough country near the scene of action but to get there fast the vehicles must have improved roads. Fortunately, civilian highways cover every part of the United States. More than 75,000 miles of our road system have been designated as a strategic military highway network. Parts of this network are modern four and six-lane superhighways that have been built to army specifications. Such highways can support heavy military traffic, including the great prime movers that tow 155-millimeter field guns at 50 miles per hour. State highway engineers are busy widening and strengthening bridges, reducing curves and grades, and increasing the width of parking shoulders along the older portions of the strategic routes. California, for example, with 1,000 miles of sea coast, has 7,000 miles of highway in its strategic system and is spending $150,000,000 for additions and improvements. Access roads that will tie air fields, training centers, and defense manufacturing centers directly into the network are also being improved. In many instances, highway engineers have considered military necessity as well as existing traffic needs in laying out new routes. A road leading down to a beach, now thronged with week-end traffic, may have been planned and built with the knowledge that it may sometime serve to rush troops and guns to a threatened spot. Coastal highways that are famous for their scenic views “happen” to have curves, grades, and fields of view that are suitable for big mobile guns. Built primarily for business and pleasure vehicles, our highway network is also a network for defense.