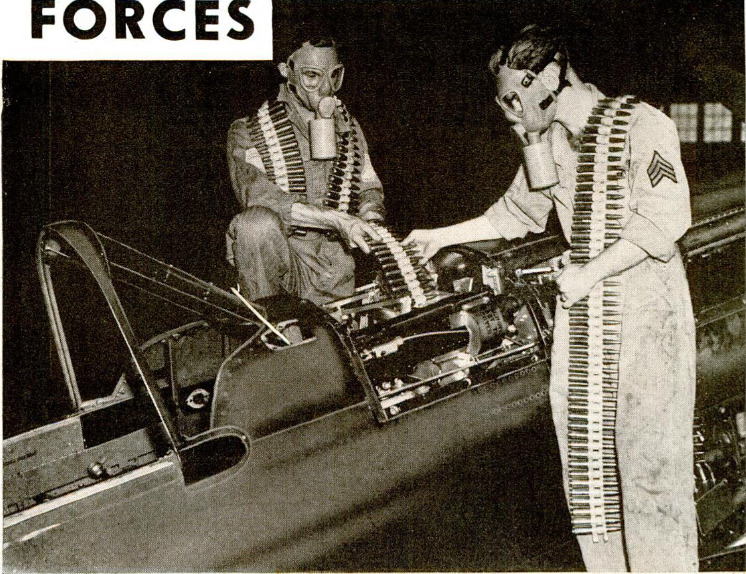

Speed Demons of the Air Forces

Contenuto

- Titolo

- Speed Demons of the Air Forces

- Article Title and/or Image Caption

- Speed Demons of the Air Forces

- Autore secondario

- Thomas E. Stimson, Jr.

- Lingua

- Eng

- Copertura temporale

- World War II

- Data di rilascio

- 1942-02

- pagine

- 56-59, 173

- Diritti

- Public domain

- Sorgente

- Google books

- Archived by

- Enrico Saonara