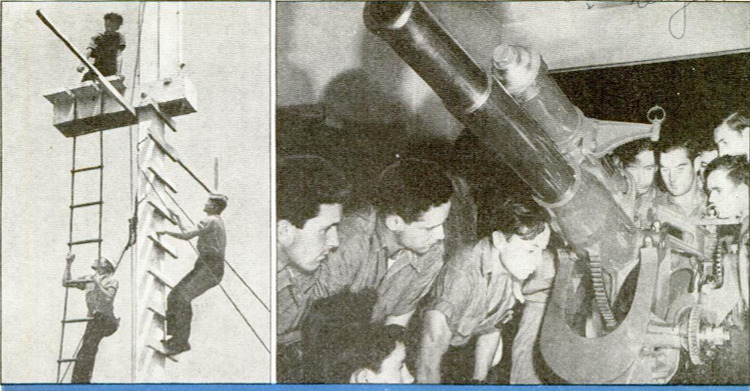

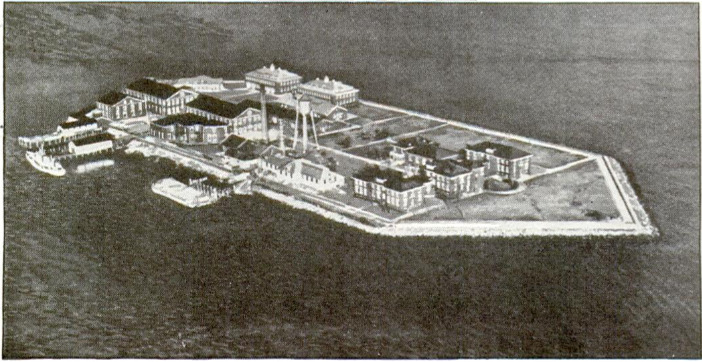

THEY call it the ship that never sails. Day after day the seas pound its sides and the wind whines through its rigging. Its lifeboats sway in the breeze. Smoke from its stack drifts over New York harbor. Its cargo booms swing up and down incessantly as though feeding a bottomless hold. Its modern guns are always ready to growl defiance at the thousands of craft which slide past, but the command of “Fire,” is never given, except in practice. Its crew of 658 men, alert and disciplined, down to the last man longs for the feel of Atlantic swells beneath their feet. But the ship that never goes to sea is anchored by wood and steel piles to a reef between the tip of Brooklyn and Staten Island. It will never move. For this ship is merely a dot in the waves, an island of seven and one-half acres - Hoffman Island - little known even to the average New Yorker and practically never heard of beyond the city. By queer coincidence it is shaped like a ship, with pointed bow, parallel sides and rounded stern. Yet it is important in America’s maritime destiny, for from here go the crews trained to serve aboard United States liners and cargo carriers - able seamen, who, seven months before, were clerks, farm lads, college students, or high school graduates still wondering which career to pick. The island “ship” is training mariners for Uncle Sam, teaching them seamanship that required three years apprenticeship at sea in the past. True, their education will have been forced along by wartime expediency, but those sailors will be worth their salaries, ranging from $7250 to $84 a month, plus living quarters and food, to say nothing of bonuses paid on ships touching certain dangerous ports. One of these bonuses hit an all-time high recently when $500 was awarded everycrewman on a ship headed into a war zone. If they were not competent, they would have been weeded out early in the training course by the officers loaned to the island organization by the United States Coast Guard, headed by Commander George E. M. Cabe and Lieut. Commander William J. Austermann. Up to now, an average of 14 percent has failed to make the grade. Early in the present emergency, the pressing need for cargo ships was recognized by Washington officials. Vessels were ordered by the hundreds. New shipyards were built, old ones reopened. But soon officials began to wonder who were going to man all these vessels. If there is anything more important than the ship itself, it is the type of men who operate her, and good seamen are so scarce today as to threaten the nation’s welfare in time of war. So the United States Coast Guard, which could furnish excellent instruction and administrative personnel, was requested by the Maritime Commission to administer the U. S. Maritime Service and produce thousands of seamen who deserve the deseription “ablebodied.” But ships are scarce and these perilous times are not propitious for sending green men aboard any craft which sails the deep. So the little speck of artificial land that once had been a quarantine station was taken over. The result is the grass and cement “decked” ship, Hoffman Island, where men from 18 to 23 who have had a reasonable amount of education are learning the ways of the sea, the twist of a rope or the feel of a deck gun, Their textbooks are nothing like the ones they studied back home. They deal with the intricacies of gunnery, the stowing of cargo, the handling of machinery, fire extinguishing, the use of gas masks, lifesaving and in general the ways of the sea in these times of modern ships and modern wars. They “cram” at their lessons willingly, because only three months at the training- station are needed before the successful ones are placed aboard a training ship for four months of actual experience off the American coasts. They know that 6,000 jobs are now awaiting the ones who make the grade, divided as follows: 40 percent for deck work, 40 percent for engine room work and 20 percent in the steward’s department. The apprentice steps from a stripped-down former Coast Guard patrol boat to behold an island looking very small in the wide expanse of the sea, and equipped with a variety of docks, slips, towers, masts, guns, cargo booms, offices, school buildings and red brick barracks. The first week or 50 he learns to make up his bunk, care for his clothes, keep his locker orderly. In this period he also gets acquainted with his fellow apprentices, examines the island ship and its many devices for training, receives rudiments of discipline, which is not as strict as in the armed forces, begins to get his muscles in shape with exercise, and takes the antitoxins which are necessary if he is to sail to tropical ports. The second week he is likely to find himself in the galley of the good ship Hoffman Island, picking up the tricks of waiting on tables, baking, broiling, boiling, roasting and frying. He is also shown that spotlessmeans spotless when it refers to the condition of eating quarters. The third week usually begins to show whether there is hope of making a sailor out of him. Cooped up with his fellow men for long periods, the seaman cannot be too morose, quarrelsome or of downright bad character. During this week he begins to find out how difficult it is to get into a swaying lifeboat, how quick he must move to his station when the emergency call sounds and he is taught how to raise and lower the boats from their davits. By this time he is talking the language of the sea and has picked up the spirit of the thing if he is ever going to. He learnsto snap into it when a fire alarm is sounded, rush to his post and handle a fire hose, or a carbon dioxide extinguisher. He is introduced to oxygen and gas masks. He hears lectures on disasters at sea such as the Morro Castle and the Halifax blast during the last war and his instructor points out the human errors which were fatal in each case. He is taught to follow routine in case of a fire at sea, or in the tense moments when a great vessel is sinking, but he is also encouraged to use his wits, for no disaster at sea is exactly like another. Motion pictures and lectures acquaint him with the methods of ship propulsion, whether by gas engine, Diesel or steam. He learns to tie knots and grasp the principles of rigging, gets used to climbing ladders of rope and wood. By the end of the first month, his training is amplified in each of these latter branches with special emphasis on boat drills. The next two weeks introduce him to the use of weapons, which range from anti- aireraft machine guns to four-inch broadside guns which are commonly placed aboard merchant craft in time of conflict. He learns to load and gets the necessary muscle, by toiling hour after hour with the 50-pound dummy projectiles which he must carry to the big guns, thrust in, and catch on the rebound when they are “fired.” There are modern range finders and classrooms where gunnery problems are worked out on regular blackboards. He is taught not only to fire weapons, but to take them apart, clean them, and even to make repairs if necessary. Soon, according to his aptitudes and desires, he begins to be a specialist, whether it be a fireman or an oiler below deck, or a seaman on deck. If he likes the cooking and waiting tables, he slants into a steward’s course. If he becomes a deck seaman, for instance, he is placed on a crew which handles the exact duplicate of a hatch aboard an ocean-going ship. Of steel construction with regulation heavy wooden hatch covers, winches and booms, the dummy hatch receives dummy cargoes hour after hour as the apprentices learn to hoist the great covers, load heavy metal objects in cargo nets, steady them while they are lifted and lowered, and run the steam winches. The hatch is only about four feet deep instead of the 25 or 30 which would ordinarily lead to the hold of a big ship. This saves many an apprentice a tumble below. By the time they have learned to operate the hatch and its engines, they have also learned how to be careful. Three months aboard Hoffman Island and they are ready to be placed on one of the training ships which the United States Maritime Commission has placed at their disposal. Among these are the American Sailor, the American Seaman, and the Epire State, ships of the 5,000-ton class. Voyages to ports as far away as the Caribbean and tropics put the final polish on their education. Thus the ship that never sails has saved them nearly two and one-half years in training for a seafaring career.