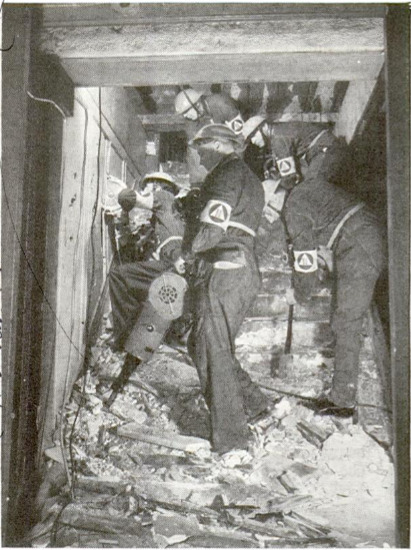

WAR quickly taught Europe the airplane had at last brought conflict to the doorsteps of the civilian and not even the most efficient army, navy and air forces could prevent bombing behind the battle front. But not until the United States found itself actively engaged did the nation begin to realize that just as the armed forces could not prevent air attacks on cities, neither could experienced firemen and policemen handle the emergencies brought about by explosive and incendiary bombs in which 1,000 fire bombs usually mean 100 bomb fires. Regardless of the efficiency of the trained forces, civilians must take a hand in their own defense. The time may come when every able-bodied American citizen, male and female, will be required to assume some protective duty in the army behind the army. The bigger the city, the better the target. This was discerned early by officials of America’s largest metropolis, New York City, with 7,500,000 people exposed to attack. For more than a year, behind the facade of business as usual, a feverish campaign of preparedness for civilian defense had been going on. The day America entered the war, over 115,000 air raid wardens, more than 25000 auxiliary firemen, and thousands of technical specialists - a civilian defense army numbering more than 200,000 - were ready for duty in New York City. From this blueprint the rapidly expanded civilian defense army of the nation has been constructed, with its now familiar homespun firemen, air raid watchers, communications experts, and rescue squads. What may be in store for the average American as the civilian defense program expands is indicated by the intensive advanced training given volunteer auxiliary firemen in New York. To ordinary fire fighting, first aid, morale building, house wrecking and rescue work, were added new problems inflicted by war hazards. They were taught that every building over 75 feet high in New York is required to have a water tank on the roof, with a standpipe reaching to the sidewalk. If a blast shattered the water main, they were to fasten a hose to the lower end of a standpipe and attach it to the engine. A 5,000-gallon standard tank provides a 20-minute stream. Fire department lectures dealt with the hypothetical situation in which all the mains had been shattered near the center of Manhattan island and several large fires were burning. The men were shown how hose lines could be stretched to the Hudson river and the East river and water pumped for many blocks by relay pumpers every 2,500 or 3,000 feet. Civilian firemen studied the location of bathing pools, the use of portable tanks and stationary water supply vats, bucket brigades and stirrup pumps. They were given instruction on emergency treatment for smoke inhalation and burns and first aid for fractures and wounds. They were instructed in the use of splints for fractures and tourniquets to stop bleeding, and how to apply bandages. Practicing in gas masks, firemen learned the necessity for decontamination after exposure to mustard gas, the fact that blisters caused by Lewisite gas must not be broken or they will form again, and the first rule in treatment of tear gas - to keep from rubbing the eyes. Air raid watchers spent hours spotting “enemy” planes from skyscrapers. First aid groups clambered through wreckage with “victims” on stretchers. Decontamination experts practiced on gas-impregnated ground. In the army information center, calls were received from many of the 1,500 observation posts around New York, and along the Atlantic seaboard 40,000 civilian spotters helped chart the course of aircraft simulating attack on New York City. Meanwhile engineers were appraising the vulnerability of the city with the most large buildings of any civilized community. They found these very skyscrapers were the greatest safety factor in the city. Except for the top six floors and the vicinity of roofs on setbacks, no better air raid shelters could be planned than the tall buildings, because the path of a dropped bomb is oblique and it is likely to be diverted from the side of a building if it strikes. Above three floors, the danger from flying debris would be nil. Half a dozen supporting columns could be blasted from a structure like the Empire State Building and it would stand firmly, they estimated. Concrete and steel floors would resist bomb penetration. The city’s 11,000 taxicabs were organized into an emergency group which volunteered for evacuating women and children, giving first aid, and transporting fire-fighting equipment if needed. Technical, engineering and art schools inaugurated classes in camouflage and light control, and disguise of strategic buildings, air field, gun emplacements and raid shelters. Replacing the national guardsmen called into service, a new New York National Guard, composed largely of veterans of World War I, was mobilized and these men topped off their civilian duties in the daytime with bayonet drills and target practice at night. Air raid drills were given school children to find methods of evacuating the million or more pupils in emergency. It was found that within 20 minutes nearly all pupils could be tagged with identification cards, marshaled into groups and dispersed to their homes under the leadership of teachers. Even blind children were given instruction as stretcher bearers, carrying other blind children through the school corridors. Specialized crews practiced at mine laying and sweeping operations in New York harbor, using dummy mines usually, but with active mines substituted and exploded occasionally to complete their training. Detailed plans for supplying the metropolitan area with the necessary 40,000,000 pounds of food daily were worked out by William Fellowes Morgan, Jr., Commissioner of Markets, and his staff. Maps and statistics were drawn to show how, for example, if the Holland Tunnel were smashed, foodstuffs ordinarily carried through this artery could be lightered across the Hudson river, or trucked over a bridge. Systems were worked out so that several weeks' supply of essential foods will be available, and questionnaires filled out by wholesalers indicated how much provender would be necessary if transportation lines to the outside were crippled. Civilians were advised to duck under a stout table if caught in a vulnerable building during an air raid; to keep suitcases packed ready for a quick departure; keep bathtubs full of water, have stirrup pumps and sand available to extinguish incendiary bombs and to evacuate all pet dogs, which have a tendency to go mad under the excitement of a raid. One novel suggestion for protection from air raiders was the proposal of A. F. Dickerson, head of General Electric’s illuminating laboratories, for a canopy of light, rather than a blackout. Pointing out how headlight glare from automobiles renders the vehicles obscure, he suggested that thousands of small, powerful searchlights, pointed skyward, would blind enemy fliers and prevent them from spotting their targets. Similar groups of lights in fields near the city would confuse the bombers. “Black light" - invisible ultraviolet rays focused on fluorescent surfaces - plays a big part in blackout schemes. Automobiles and buses, arm and hat bands and even warning signs glow with luminous paint at night, although invisible to aviators. Engineers found that street lights can be dimmed to a soft glow, making objects visible for 25 feet, yet furnish no light that can be observed from a bomber. “This would also save current for war-time industry. Recommended for the blackout is a “black out sheet” of black paper which sticks to the inside of windows and bars escaping light. It also prevents glass from flying in the event of a nearby explosion. Another shutterlike sheet lets daylight in, but prevents light rays from escaping at night. Power plants may be covered with huge “tortoise shells” of reinforced concrete to resist bombs. Mobile power transformers are standing by to restore power should a regular substation be put out of operation. These four-wheel trailer units can be atached to an automobile and rushed to the scene of emergency, and provide electricity for 15,000 homes apiece. Museums arranged to ship priceless objects to rural points. Such objects as the two-story dinosaur skeletons in the American Museum of Natural History will probably take their chances with bombs because of the difficulty of removing them. An ingenious plan has been approved by which defense directors, using airplanes, navy blimps or,vantage points atop the highest skyscrapers can direct the thousand or more radio-equipped police vehicles through the streets in an emergency. Cruising above the city in two airplanes, defense engineers testing the scheme were able to keep constantly spotted a black sedan with the word “TARGET” painted on its top, as the car moved in traffic below. A dozen or more trailer fire pumps have been tested by the authorities. A typical unit will throw two two-and-one-half inch streams of water 75 feet high. These can be towed by hand over debris-strewn streets impassable to regular fire equipment. Railroads are planning portable trestles by which traffic can be routed over and around bomb craters. A suit with plastic-braced ribs which protects the firemen from the concussion of a bomb explosion has been invented. Front, back and shoulders have laminated plastic inserts and the fabric is noninflammable cotton gabardine. Also tested by defense experts is a 90 mile-an-hour motorcycle ambulance. It has a seven-foot sidecar to carry the patient and a medical attendant. A newly developed “alert” receiver turly on automatically when it catches an inaudible air raid signal from a broadcasting station, rings a bell to summon listeners and shuts itself off when the “all-clear” is sounded. The receiver can be fixed-tuned to any station. Plans have been considered for underground factories, buried under 80 to 100 feet of rock where defense work can continue under strafing. Films from England are to be shown to New Yorkers demonstrating how to extinguish incendiary bombs. The favorite method is to drop a sand bag on the bomb, which usually smothers it in two minutes.