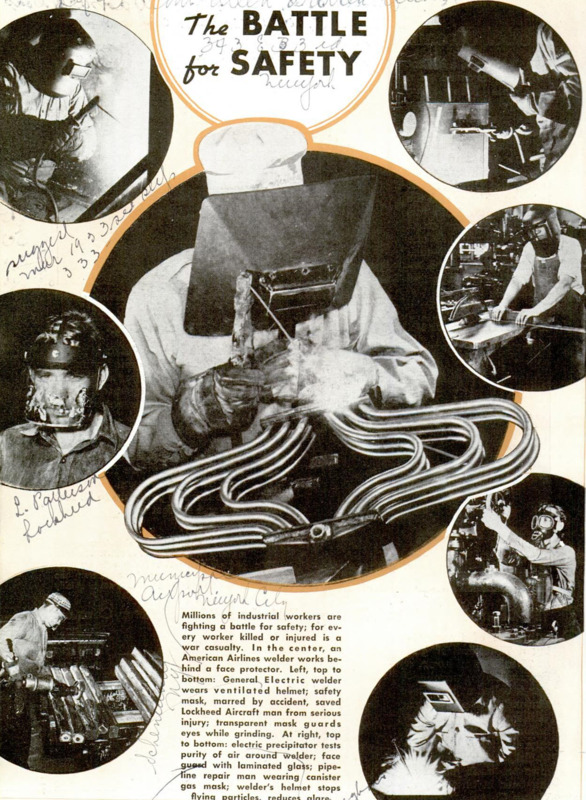

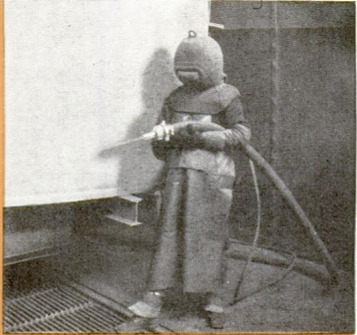

LONG before the shooting war began, the casualty lists were mounting. American factories are America’s first line of defense, and throughout the vast industrial machine soldiers with tools were dying by thousands, being maimed and disabled by more thousands, in a “blitzkrieg” led by General Carelessness. Production was mounting swiftly, but the accident toll was swelling at a higher rate. Industrial safety experts and government men, alarmed by the loss of men and man-hours, got busy. They found that while general employment increased only two to three percent in 1940, industrial deaths jumped ten percent from 15,500 to 17,000. In 1941, fatalities may have reached above 20,000. With millions of green workers added to payrolls, all more or less unfamiliar with shop and plant routine, with manufacturing programs speeded up, with many “rusty” old hands recalled from retirement and with tiring overtime hours the rule, the accident toll has appreciably slowed the country’s arming program. But the tide of the battle for safety is believed to have been turned, thanks to the use of scientific and mechanical safety devices plus an intensive campaign of education directed at the executives of small, “mushroom” defense plants. The larger corporations are not responsible for the sharp increase in accidents. Because of never-ceasing safety drives and ingenious protective measures, their accident figures have shown a steady decrease. The average citizen who seldom sees the interior of a factory would mistake many modern workmen for warriors from Mars, equipped as they are with masks, respirators, goggles and face shields, head guards, Neoprene clothing, rubber aprons, metal capped shoes and asbestos outfits. Bethlehem Steel protects open hearth men with asbestos clothing; trimming machine operators have flexible cords attached to wristlets, and if a man’s hand advances into the danger zone, the cord tightens and pulls a switch, stopping the trimmer. American Airlines has installed artificial waterfalls in its shops to eliminate dust and anti-corrosion spray. At a Westinghouse plant, elec- tric eye mechanisms spot a welder’s hand when he reaches into a giant stamping machine and stop it as the light beam is broken. Jones and Laughlin Steel Company spent $40,000 extra on a new building so that a 15-inch clearance could be left between overhead electric cranes and the building columns. The cranes are also provided with extra brakes on the jack shafts and miniature red and green traffic lights automatically tell whether the operator is in his cab. Caterpillar Tractor Compiny uses ventilated work benches from which dustladen air is pulled down through a grill into filters; fire blankets are at hand to wrap around a man whose clothing is ablaze. General Electric lost only one man by accident during 1940, despite the rising national trend. This man broke a leg falling from a ladder and died of pneumonia. Westinghouse had the lowestaccident rate in the company’s history. General Motors established a safety record in its 89 plants with a lost-time accident record of only 343 for every million hours worked, and one plant has gone three years without a lost-time accident. The Bayuk Cigar plant in Philadelphia established a new American record when its employes reached 14,314,436 work hours, before a lost-time accident occurred. The United States Steel Corporation and its subsidiaries has brought its accidents per million man-hours down from 79 to 6.84, since 1913. The Jones and Laughlin Steel Corporation’s, seamless tube department. rolled up 28,000,000 man-hours without a fatal work accident, while in the same period, 12 employes met death by accident outside the plant. In the front lines of the battle for safety is the National Safety Council. This organization has found the ten safest industries are tobacco, cement, laundry, steel, glass, automobile, textile, rubber, chemical, and printing and publishing, with disabling injuries ranging from 2.77 per million man-hours in tobacco to 8.81 in printing and publishing. The ten most hazardous industries are paper and pulp, tanning and leather, woodworking, marine, clay products, foundry, refrigeration, construction, mining and lumbering, ranging on the same basis, from 15.38 to 45.50. Analysis of industrial accidents by the council showed that more than one fourth were caused by plain carelessness. Of the mechanical causes, hazardous arrangement of machinery led the list, with lack of safety guards next. Other contributors were defective machines, unsafe apparel and scanty illumination and ventilation. Improper attitude toward safety and lack of knowledge or skill had some part in 85 percent of tabulated accidents. Finger injuries were 22 percent of the total. Other portions of the body in order of vulnerability are the trunk (20 percent), legs, arms, feet, hands, head, toes, and eyes (4 percent). Leonard Cole, Safety Engineer for the Crane Company, and member of the National Safety Council, offers five “don’ts” for workingmen: don’t fail to use safety appliances, don’t touch a machine until you know how to use it, don’t get thoughtless or indifferent while on the job, don’t try short cuts when there is a safe way of doing a job and don't leave tools and machinery around the floor for someone to trip over. The army of skilled workers forms a tremendous asset and this investment should be protected, L. S. Hawkins, Director of U. S. Vocational Training for Defense Workers, points out. “During the past year, more than one million men and women were trained for the defense industries in vocational schools,” he says. “Ten times as many already have been trained in pre-employment courses as were trained during World War I. It is apparent that a considerable investment in the training of an individual may be entirely destroyed through an accident. “The great majority of accidents result from the failure of some individual rather than from causes which cannot be foreseen. Induction of many new workers tends to increase these hazards unless appropriate measures are taken to guard against them. Accidents can be reduced through organized training programs and safety devices not only for the good of the worker, but to protect the public's interest. “It is much more humane and more economical to take every possible precaution to protect the worker than to prepare a replacement. Safety training and safety precautions are an indispensable part of the defense effort.” If you spent fifteen minutes reading this article during normal working hours, the chances are at least two men went to their deaths in an American plant or factory - crushed by falling metal or stone, dragged into a whirling machine, burned, mangled or fatally infected. From 160 to 180 men were injured.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 3, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 3, 1942