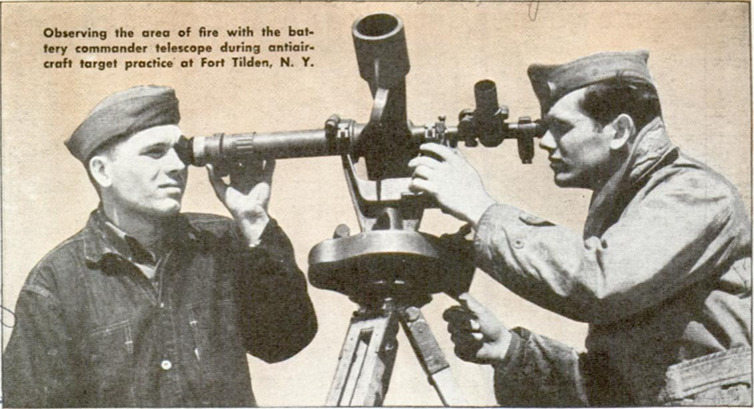

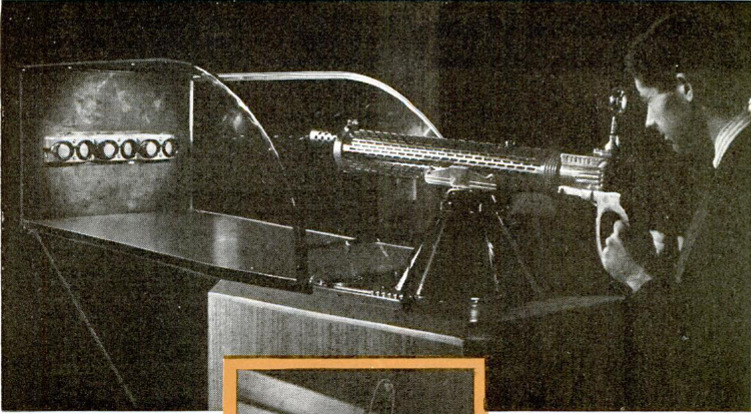

SEVEN miles above the earth aerial cameras are plotting the terrain of a military engagement. Hollywood is on the threshold of a revolution wrought by new methods of using lenses. New spectacles are freeing the color-blind motorist from danger. The greatest lens the world has ever conceived will soon be ready to reach into uncharted spaces of the universe. Centuries ago men learned to bend light rays with glass, and few single factors have influenced the course of civilization so much as the lens. Yet men learned slowly how to put it to work. Spectacle lenses arrived about 1290, then nearly 330 years passed before a Dutch spectacle maker evolved the telescope. In the last few generations remarkable advances have been achieved in sight, photography, motion pictures, lighting, radio, television, medicine, biology, bacteriology, metallurgy and astronomy. Today the rate of progress is phenomenal. In New York, experimenters led by Dr. Alfred N. Goldsmith, known for his radio and television discoveries; have developed a new use of lenses which will revolutionize movies when Hollywood adopts the method, which is not likely to be long because it solves one of the most baffling puzzles that has confronted the moving picture industry. One basic difference between watching a stage play and a movie is that your eye has no fixed focus and can follow a performer around the stage, keeping him always in clear view. Compared to the eye, however, the motion picture camera has been a crippled organ of vision because it has a fixed, or limited foeus. For this reason, unless the camera is moved with the performer, he fades into a blur as he steps out of focus. That is the reason you have had to put up with annoying “close-ups” followed by “long shots” which break the continuity. They are merely clumsy subterfuges which hide the weakness of the camera which cannot give you both at once. Soon you will be able to follow all of the performers clearly wherever they move, as the result of the discovery recently patented. Movie sets are to be divided into zones, according to distance from the camera. Each zone has an independent bank of lights. These lights flash on and off 48 times a second, so fast that to the eye they seem constantly lighted. But the camera is faster than the eye, and in front of the machine, instead of the limited single lens, whirl a number of lenses, one for each zone. As the lights flash on in a certain zone, the lens which keeps that zone in focus whirls in front of the camera. Each frame of movie film is exposed several times so that whatever shows in each zone is photographed on it separately. The result is that an actor is in focus wherever he may be and his features are as sharp at 50 feet as at three. War conditions naturally have hastened research to equip the military forces with the best “eyes" science can develop. Major George W. Goddard, chief of the army photographic laboratory at Wright Field, Ohio, predicts the ceiling for aerial photography will soon rise considerably above 40,000 feet where flying photographers would be safer from attack. Army cameramen have made pictures at 35,000 feet in temperatures 30 to 60 degrees below zero, requiring heaters on the cameras. One important improvement to this branch originated in the laboratories of Bausch and Lomb Optical Company at Rochester, N. Y, where a new lens enables a single photograph taken straight down to show accurately three times as much area as previously possible from the same altitude. This remarkable lens will take a photograph at a height of three miles in which every detail of the landscape is clear within an area of 28 square miles. Covering a field of 90 degrees, it is also possible to photograph fortifications, plants or troop concentrations without flying over them. With aerial light bombs, and better lenses, color photographs can be taken from military planes at night with such effectiveness that they penetrate camouflage. The flashlight bombs give billions of candlepower over a wide area. By using different colored flashes and various color films, camouflage dependent on color is exposed. Also developed in the Bausch and Lomb laboratories is a stereoscopic map projector used by U. S. military forces. By the use of overlapping photographs, transferred to glass plates, one lighted green and another red and viewed through spectacles with green and red lenses, a three-dimensional effect is obtained, so realistic that it appears possible to put one’s finger on a smokestack, although it has been reduced to 1/25,000 of its real proportions. As the result of the research of this company, which was awarded the Ordnance flag and Navy “E” pennant for outstanding production of naval ordnance instruments, military commentators believe the United States navy now leads the world in development of fire control instruments on warships, with Germany second and Great Britain third. These range-finder instruments are closely guarded secrets, yet it is known they have grown so complicated and precise that a range finder may consist of 1,500 mechanical parts with almost 100 lenses, prisms and sections of optical glass. It takes half as long to build a range finder as it does a towering battleship, but when they are finished neither the shock of thundering salvos nor the vibration of engines affects their use. Also brought up to a new standard of efficiency are the range finders for huge coast-guard guns, antiaircraft detectors, height finders and military binoculars, which are subjected in testing rooms to man-made hurricanes to make certain weather will not cause failure. What is termed the first major advance in optical glass since 1886 has just been developed by the Eastman Kodak Company. The entire production is being turned over to the U. S. military air service for mapping and observation purposes. The glass is made without silica, which is comparable to making steel without iron. It is characterized particularly by high light-bending ability with a minimum tendency to spread light out into a spectrum, and gives greater lens speed. Improvements in the use of polarizing methods, in which an inserted sheet of film acts like a picket fence, excluding from lenses the rays which cause glare, have also resulted in assistance to the armed forces. Laminated Polaroid lenses have been devised which can be ground and polished to such a degree of precision they can be used in fire-control instruments. The filtered rays are so precise that a light projected through these lenses would be refracted less than a yard at a ten-mile distance. Reduction of glare is also proving an important factor in submarine and torpedo detection, since the polarized lenses cut through the surface reflections of water and disclose what is beneath. Nor have the discoveries been confined to movies and war, for thanks to the combined research of Dartmouth University Eye Institute and the American Optical Company, a condition which has puzzled generations of eye specialists has been remedied. Thousands of cases were encountered in which the fitting of new lenses to defective eyes failed to clear up headaches, dizziness and even upset stomachs, until it was learned that all people do not see equal images with both eyes and the difficult task of adjusting one image to the other was raising havoc with their nerves, though their sight might appear perfect. The disease was called aniseikonia. American Optical Company scientists have devised a lens that corrects the condition modifying the image as seen by one eye. Although Benjamin Franklin gets the honor of inventing the first bifocal lens in 1775, when he simply cut two sets of lenses in two and put the thick reading glasses in, the bottom of his spectacles, it is only recently that bifocals, which correct near and, distant vision in the same pair of glasses, could be manufactured without leaving at fuzzy area where the two types of glass were joined. Dr. William Feinbloom of Optical Research, Inc., in New York City, has won a science award for combining plastic rims with glass lenses in contact lenses, which are fitted directly to the eyeball. Another New York eye specialist, Dr. Brittain F. Payney devised the spectacles for color-blind motorists. The upper segment of the spectacles is red. Looking down the street, the motorist sees only the red or orange light, which warns him to stop or slow dowr. The green signal is never visible, so when no light is seen, the motorist knows it is all right to drive on.