-

Titolo

-

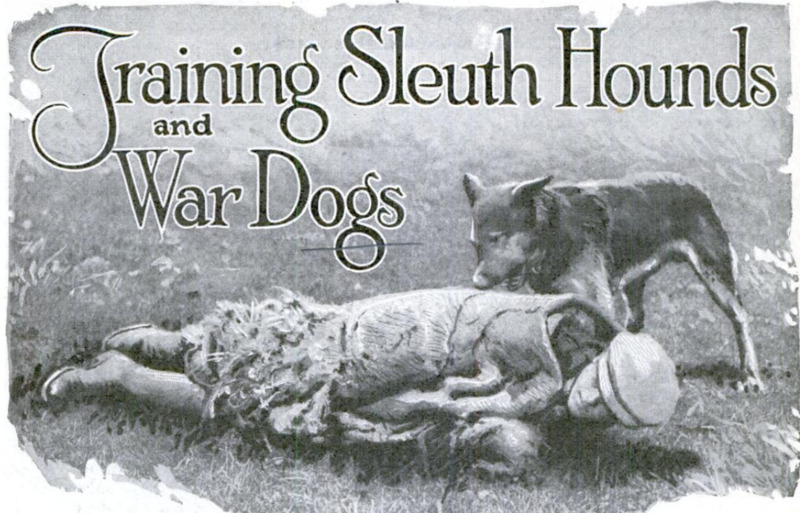

Training Sleuth Hounds and War Dogs

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Training Sleuth Hounds and War Dogs

-

extracted text

-

THE sharp ringing of a telephone bell, at midnight, startles the inmates of a quiet country house, deep in the heart of rural lanes and surrounded by wooded hills, many miles from a railroad depot. Jumping from bed, the owner of the house grasps the receiver and finds himself speaking to a police officer 400 miles away.

"Come at once. A murder has been committed here. Rush your bloodhounds by auto. Don't wait for a train." The listener goes back to his room, and hurriedly dresses himself, after ringing up his chauffeur and telling him to get ready the auto. A swift toilet, a little food and drink thrust into a handgrip, and the owner walks quickly across lawns and walled fruit gardens to a block of clean-looking kennels. Inside are three magnificent coal-black mastiffs, with long pendulous ears, and deep, red-ringed eyes, shining like rubies.

They are pure-bred bloodhounds, highly trained, tenacious when hunting the trail of a wanted man, yet as gentle and affectionate as any puppy. Their natural quarry is man. Once these hounds are put on the trail, a murderer has an uncanny feeling that it is futile to try to escape, since he may be tracked down to his very door.

Seventeen hours later the hounds are entering the streets of a busy Scotch seaport town.

A severe frost, rendering the ground unfavorable for scenting, will put the bloodhounds' keen noses through a severe test.

The murderer has been traced to a spot on the cliffs where he has discarded some clothing. The owner takes his hounds to the spot, and they show true signs of their breed at once by walking with their noses to the ground. They sniff the articles discarded by the murderer, and cast around a little. The scarlet haws of their eyes gleam, and they are away.

The main road is followed for some distance, then the hounds leave it to cross a field. They trot through a wood to a cottage, but here they seem at fault and run about whimpering. A police officer knocks at the cottage door, and learns that, shortly after the murder. a man called and begged some water. Hearing this, the owner casts his hounds right and left round the cottage in order to pick up the scent. The bloodhounds run to and from, persistently sniffing. A deep bloodcurdling bay breaks from one of them, in which the others soon join, and they open out on a line beyond the wood. They cross fields at a short trot, and abruptly break off into undergrowth. Presently, the trail debouches on a high road, where it seems lost again, but the hounds, un-daunted, keep steadily on, till they find the scent.

They lead the police across country roads and fields to a town and straight to the vicinity of a railroad depot, where all trace of the fugitive is completely lost. It is plain that the criminal has got clear away and is not hiding in the neighbor-hood. But the police have now got a working clue, and by vigorous action and the use of the telegraph and telephone are able to arrest the murderer, a few days later.

For police tracking, the vital part of the bloodhound's work is not so much that it may run a criminal to ground, as that it indicates the direction a criminal has taken after his crime, and gives the police a chance to wire or phone details and descriptions. Night and dawn are the best hours in which to put a bloodhound on the trail, since the scent is good, and criminals who rush across country, avoiding roads, seek the shelter of woods and undergrowth and fields, where the scent is caught and retained. On the other hand, in the towns the scent is soon broken and lost. If a police station has a bloodhound kennel, the chances of successfully tracking down a criminal immediately after the crime are immensely increased. The hound can be put on the scent while it is still fresh and undisturbed by vehicles, the police them-selves, or sightseers attracted to the scene of the crime. The bloodhound has to be highly trained for Police work, for every bloodhound cannot track. Its education is long and varied. It has to track its quarry through suburbs and across fields and footpaths where the trail is fouled, and it must be able to follow the scent on or off a leash. As soon as it reaches the trail, and the scent is good, it is put on a leash, consisting of twenty or thirty yards of strong rope, coiled to give play. Hot on the scent, the bloodhound will break into a fast trot requiring all the effort of the policeman to keep pace with it. The bloodhound's most remarkable characteristic is that it can follow a cold scent.

The bloodhound has a long and very interesting past, dating from the time when it was first brought to England by William the Conqueror. who obtained it from the abbot of St. Hubert. in France. There are two strains of them--the black and the white. From the white is thought to be descended the old southern slave-hunting hound, heavily dew-lapped and slow-tracking, now almost extinct.

America's bloodhounds are the black and tan, southern foxhounds, used to trail escaping criminals over large tracts of sparsely inhabited country. A dash of ferocity is encouraged in these hounds, and they may show their teeth; yet one of them, over whose head was shot a notorious murderer fleeing from justice, was as gentle and affectionate as a child.

Great expense is attached to the maintenance of a kennel of bloodhounds. An adult hound. pure-bred and trained, may cost from $200 to $800. and their breeding renders them very liable to distemper. Collies and airedales have splendid noses for scenting. joined to greater intelligence. but for man tracking. the blood-hound, with its inherited qualities of indomitable perseverance, has no equal.

Few or no pure bloodhounds now exist in America. since, when they were imported here some years ago. they were crossed with other breeds to save them from distemper.

Hounds are not the only dogs used in police work. All over the world, English airedales, various breeds of European sheepdogs and terriers with their fine qualities of intelligence and powers of scent make good sleuths. German police employ airedales and the "Dobermann pinscher," a dog resembling a black-and-tan terrier. Los Angeles recently bought ten Alsatian dogs to be used on police-patrol work. They cost $15,000.

New York City at one time kept a brigade of highly trained police dogs, at first bloodhounds, then Belgian sheepdogs. These dogs went to the aid of people found ill on the streets, or lying on the ground frozen in winter, and they helped to make arrests. At present, dogs are not used there for police purposes.

The European continental police dog has a dual function. He is either an "executive" or a "sleuth dog." If the former, he accompanies the policeman on his night rounds. scouting in lonely roads, in the gardens of suburban houses or in parks. He warns the policeman of anything unusual or suspicious in the immediate neighborhood. Exceedingly savage and suspicious, the dog has to track down desperate characters, which he does to the extent of clearing out dangerous people in rough quarters of the towns.

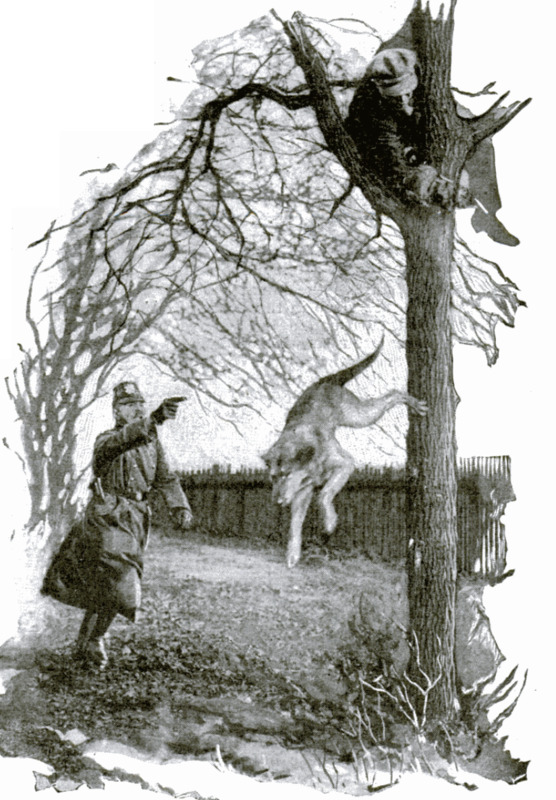

If he has good scenting powers, and can run down cold trails, he becomes a sleuth dog, and is called in when the criminal has got clear away and the scent is bad. These sleuth dogs. are kept at different centers where they can be telephoned for in. emergency. They are taken in autos to the scene of the crime, and, like the bloodhound, give important clues to the whereabouts of the criminal, even if they do not always succeed in trailing him to his hiding place. Such a dog is trained to stop burglars escaping, which he does by jumping or swimming where a policeman would be hampered by his uniform. The German and Belgian law courts regard the work of the police dogs in tracking as contributory evidence in establishing guilt.

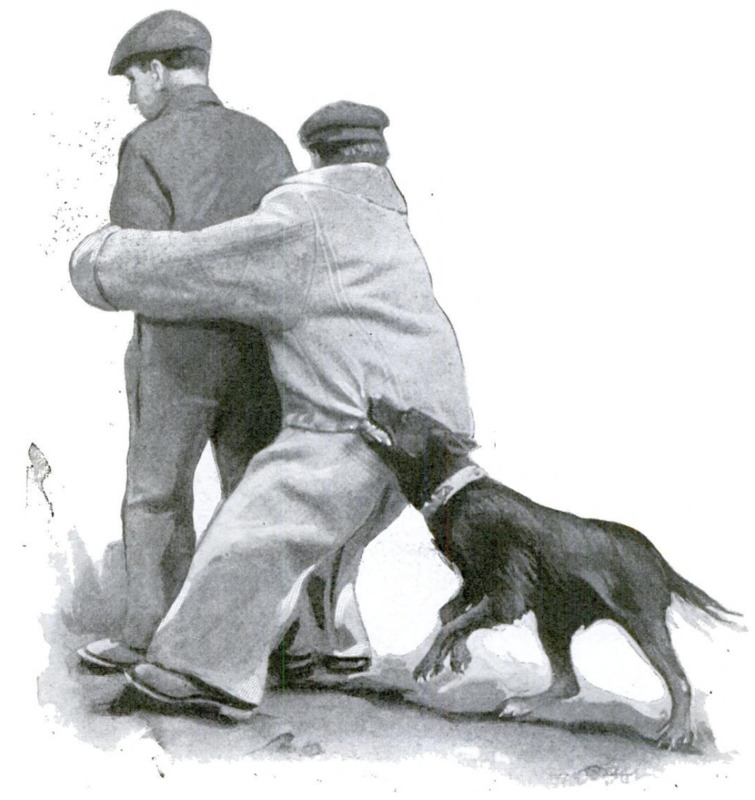

Belgian police dogs are prick-eared, smooth-coated sheepdogs of medium size, who accompany their masters on night rounds. They are treated kindly and never struck or whipped. Each kennel looks on an outside yard, surrounded by a high fence. The dogs cannot see each other, and bark incessantly, and as they cannot see the public, they do not become accustomed to the sight of strangers. They bark whenever a person passes. On the dogs' collars are a series of sharp points to repel attacks. They are savage if they see policemen attacked, and are trained to leap at the attacker's throat, and throw him over. When the attendant is training them, he dons two thickly wadded suits and a heavy helmet and wire mask, but, even so, he often is severely bitten.

These canine detectives are doing some remarkable work today. At the castle of the Austrian prince von Fuerstenberg, at Salzburg, jewels of very great value were stolen in the night. No trace of the thieves could be found for some days, until police suspicion fell on the prince's valet. They put a police dog on his scent. The dog ran to a lonely part of the grounds of the castle, where was a disused well. Here, under boards, an empty jewel box, hidden by the valet, was found.

In England, conditions are different. A police dog can be sent into gardens, yards and around empty houses, while the policeman patrols the road. The animal can hear sounds 400 yards farther away than a man is able to do, and his senses are acute at night. He will give chase where a uniformed man could not pursue. English police dogs are trained after dark, when they are sixteen months old. They are taken out on a lead of a double-swivel chain, and muzzled. If the night is wet, the dog wears a waterproof coat, which is carried on the policeman's belt. The dog starts his beat on the lead and his attitude 'tells the observant policeman what is passing in his mind. On lonely roads, the dog is off the lead and muzzled to save him from picking up poison. On the lead, he is not muzzled, so that. in emergency, he can use his teeth. These dogs are kenneled in comfortable quarters, with plenty of fresh air, pure water and clean straw. Their quarters are inaccessible to the public, to guard against the possibility of poison being thrown to them.

Alsatian police dogs, or German sheepdogs as they really are, are popular with the authorities. At the Crystal palace, London, a short time ago, they were put through severe tests. They had to track a man across scrub, grass land, miles of country and suburban roads, and ponds; pick him out of a crowd, help the policeman to arrest him, attack him if he attacked, and stop when the quarry did. They had quickly to respond to a recall, and stand fast against gunfire or blows with a stick.

A corps of airedales is used at Hull and Cardiff docks to aid the police in routing out pilferers from the recesses of labyrinthine warehouses.

A police dog, "Sauer," at De Aar, South Africa, succeeded a short time back in establishing the innocence of suspects, and tracking down a native thief who had broken into and stolen money from a minister's house. The thief, in his escape, left the parson's portmanteau on the veldt. Twenty-five hours later, "Sauer" was given scent from this, and led two detectives to a gaol, where he barked at the door, and strained on the leash in his eagerness to get inside. In the prison yard, the dog made straight up to a prisoner, waiting trial on another charge. The native denied all knowledge of the offense, but when he was taken outside, the dog picked him out from hundreds of other natives, and he was charged and sentenced.

Before the war of 1914-1918, it was thought that dogs would have been of great use in finding and bringing back to ambulance stations wounded and missing soldiers. Accordingly many army staffs enlisted corps of highly trained dogs. But after the outbreak, it was discovered that ambulance dogs could not be used. A very remarkable part was, nevertheless, played by dogs in the World War.

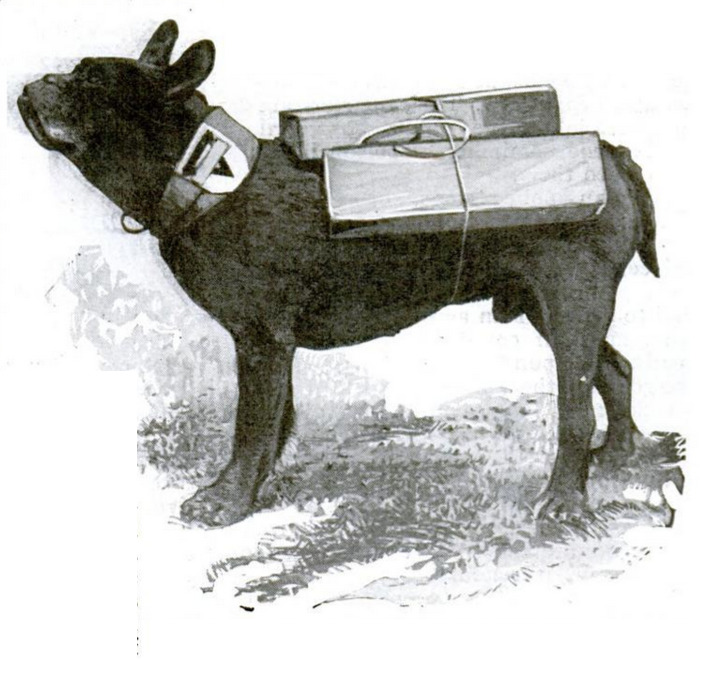

The American war department formed training depots for dogs, which were to carry messages between outposts and batteries during heavy bombardments, when telephones were out of action, and human carriers certain of death. The British war office also set to work to train dogs. In their training quarters these dogs were within sound of the firing at the front, which it was thought would accustom them to the noise of warfare. Soldiers were schooled to handle the dogs, and after five weeks, went with them across the water to a French depot. The dogs were next drafted to sectional kennels behind the front, and then sent right into the firing zone.

Great patience and gentleness were necessary to accustom the dogs gradually to the noise of gunfire and the terrifying flash and scream of shells. War dogs were and are trained to travel alone, carrying messages or food on their backs, along high roads, in and out of heavy motor traffic, over rough tracks, and past cook houses and other temptations. They have to ignore preferred food, and not dally to be patted and caressed by soldiers and civilians. They go through barbed-wire fences, leap over and creep through obstacles, swim dikes, ditches and rivers, pass through smoke barrages, dodge the pinging bullets of concentrated rifle fire, and finally enter and survive a hell of shellfire and bursting bombs which would be certain death to a man. A collie took a message to headquarters and saved an infantry regiment cut off at Cambrai. Another dog carried telephone wire across exposed ground; a crossbred dog could detect the approach of gas long before human beings could do so; an airedale was trained to go on the roofbeams of a demolished house and act as a lookout. "Kust," a French war dog, warned his regiment that Germans were hidden in a wood. An American dog, blown up by a shell while carrying a message, came down on his four feet, grubbed about for his message and trotted off to deliver it.

-

Autore secondario

-

Harold T. Wilkins (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1925-12

-

pagine

-

915-920

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Alberto Bordignon