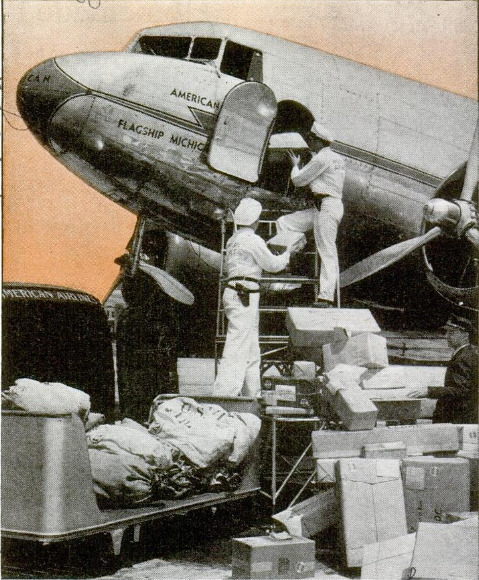

WHETHER it’s a live chinchilla from South America you want, a fresh-caught 200-pound turtle from the Galapagos or a ton of precious seed from a nursery 3,000 miles away, you can have it tomorrow by air freight. You won't believe until you see it? Well, you won’t have to wait long. Air power is revolutionizing the world, militarily, politically, and economically. Tomorrow, man will fly the bulk of his important cargos and think nothing of it. The B-19, the Army’s giant bomber, has passed its tests. Gross weight of the B-19, the world’s largest plane, is 70 tons, or 140,000 pounds; its useful load, 28 tons. This huge aircraft can fly 7,000 miles nonstop, the distance of a round trip between New York and Paris. Planes somewhat like it will be the aerial freight cars of tomorrow. With its tremendous range it brings Europe and South America within a few hours of New York or Chicago. The Army Air Freight System flies cargo on regular schedule between Air Force units throughout the nation and the Panama Canal. But what of commercial air cargo services in the United States today and tomorrow? Several plans have been tried; none has succeeded as Americans would have them succeed. Why? Because the airplanes used would not operate economically enough to get the volume necessary for reasonable return. The railroads do not use a modified passenger car for freight. They use equipment designed for cargo. That is what the air industry must do. The planes now carrying passengers, mail and express, were designed primarily for passengers. Cargo space is limited. The problem, then, is to develop aircraft and methods of handling cargo that will permit even lower tariffs. In 1940, about 869 percent of the domestic air express traffic was handled by American Airlines, United Air Lines, Transcontinental and Western Air, and Eastern Air Lines. Recently, these four formed Air Cargo, Inc,, to survey the potentialities of the cargo field -aircraft requirements, traffic flow, markets, tariffs, all factors pertinent to efficient operation. After this war, civil aviation will develop at such a pace that instead of 235 airports now served by our air lines there will be a thousand or more with scheduled service. A huge surplus of military aircraft will be disposed of for commercial use. Big bombers undoubtedly will be available for cargo transportation, An air cargo system offering a five- and six-hour service to every section of the nation, Canada and Mexico, will place industry at the source of many materials; factories can be located near cheap power and airports quickly constructed to provide air service. Shipments weighing 200 to 600 pounds are being transported by air express today. Heavier shipments are handled by special arrangements, and plane-load lots of 3,500 to 5,000 pounds are not uncommon. The average person conceives of air express as a sort of stunt service by which perishables, from foodstuffs to a movie star’s lock of hair, are sent by air just to get attention. Such shipments are handled, but air express also functions as a vital arm of the world’s communication system. For example, 30 electric heating units for an Australian steel company were shipped by air from Buffalo to “down under.” Without air express it might have taken three to four months to effect delivery. By air, the shipment traveled by American Airlines from Buffalo to Los Angeles, by Clipper to Sydney, Australia, and by Tasman, Empire Airways, Ltd., to Waratah, N.S. W. From Chicago, an air liner carried a 600-Ib. roll of cable to Texas, to be used in connection with a new Air Force training school. When a big motor broke down in a west coast plant, armature windings weighing nearly 3,000 pounds were rushed by plane from the east. Dies, tools, crank-shafts are being flown to keep the war program moving at top speed. Blueprints, data, orders, travel between Washington and war factories in a few hours. In World War I the same shipments required days. In Alaska, mining equipment is flown into location. Livestock frequently is air- shipped in our neighbor countries to the south. The role of air express in speeding serums and medicines into areas stricken by flood and fire is well known. One laboratory furnishes serum to the U. S. Navy on a 24-hour basis by air express. Producers of wearing apparel are the largest users of air express. Newspapers, cut flowers, perfume, jewelry, financial reports, cancelled checks, gold, rubber sponges; well, you name it and chances are it goes by air. It was back in November, 1910, that the first air express shipment, a bolt of silk weighing 22 pounds, was carried from Dayton, Ohio, to Columbus, in a passenger’s lap. In November, 1940, just 30 years later, the largest air express shipment in history, 36,000 pounds, originated in the same city. It was a magazine’s election issue. Commodities carried by air express have been unusual, as well as commonplace. Bette Davis, the screen star, received a New England dinner, boiled in Boston, by air at Hollywood. What were claimed to be the ashes of Columbus were shipped by air from Los Angeles to New York. The season’s first catch of trout from a New Hampshire stream was sent by air to President Roosevelt. A Chicago bakery, interested in a new oven, forwarded to New York by air a case of unbaked pies. These were baked in the oven under consideration, air-expressed back to Chicago, tasted and the decision made. Planes brought 500 pounds of rubber seeds from the Dutch East Indies to Dallas. A Chinese in New York had a stomach ache. Remembering an herb remedy in China, he decided these herbs must be got- ten from his native land. He got them. They were packed down the Burma road, sent by ship to Hong Kong, by clipper to San Francisco, by plane to New York - a distance of 11,000 miles at a cost of $4.99. The longest air express shipment flew 18,000 miles from New York to Cairo, Egypt. It was a box of sample uniforms for the British Middle East Command.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 4, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 4, 1942