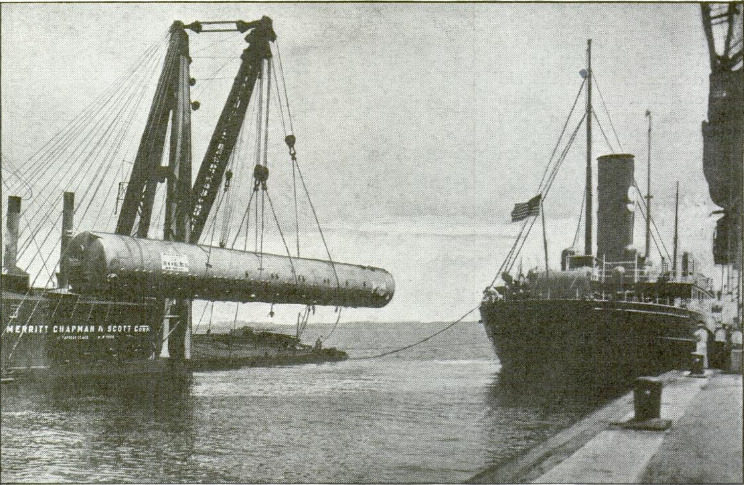

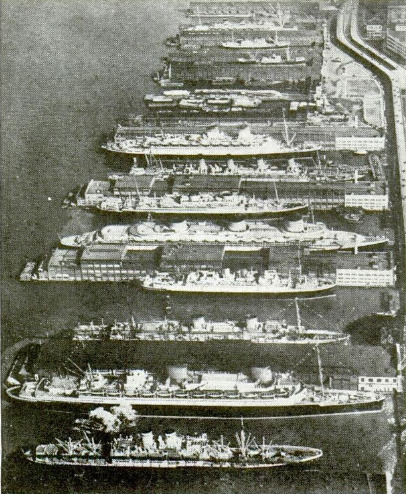

THE port of New York has passed its first test of the war as western anchor of the British Empire’s lifeline, as repair point for many of Britain’s warships, as host for hundreds of Uncle Sam’s war vessels, as a huge shipbuild- ing center, and as the clearing place for raw materials and finished weapons in the defense program. And, on top of all this, it has the role of supplying many needs of more than 12,000,000 inhabitants in the immediate area. During a recent month, 1,170 vessels of a net aggregate of 3,935, 099 tons, a large percentage of the whole world’s shipping, arrived and departed. Today the total is even larger, and the port, which is big enough to hold every ship afloat on the globe, is operating at a higher pitch of activity - but still smoothly - a decided improvement over the days of World War No. 1 when the port was regarded as a huge bottleneck. Up the great bay, past the Statue of Liberty, slide the motley vessels of dozens of nations, loaded with copper, coffee, sugar, beef lumber, coal, tea and other raw materials needed here. Down go these ships, pressed low in the water with airplanes, ammunition, guns, tanks, machinery, and food and products that have been processed in America’s plants. After the sad experience of the last war, the states of New York and New Jersey agreed to erase boundary lines and proceed with development of the port under a single body, the Port of New York Authority. What has happened meanwhile explains how the port has become gateway to the world, a huge focal transportation point 1,500 square miles in area, with wharves, piers and quays extending along 650 miles of waterfront and embracing hundreds of municipalities and civil subdivisions. And how 120,000,000 tons of commerce valued at more than $§10,000,000,000 is moved quickly even in a normal year. The problem was found to be mainly that the very harbor, rivers, canals and inlets which made the port the greatest in the nation were the cause of delay because they separated the New Jersey shore from the shores of Manhattan Island, Staten Island and Long Island, all of which are parts of the New York metropolitan area, and even these sections of New York were not sufficiently well linked with each other to move either passenger or freight traffic with dispatch. With other organizations, state and municipal, following the pace set by the Port Authority, 26 crossings have been constructed in about two short decades, including the Holland Tunnel, Lincoln Tunnel, and Queens Midtown Tunnel, the George Washington Bridge, Triborough Bridge, and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge, any one of which would be considered an engineering feat of first magnitude in itself. Preliminary work is under way on yet another tunnel, the "Battery-to-Brooklyn tube, which will extend to Brooklyn from the lower tip of Manhattan, These bridges and tunnels enabled trucks to take part of the load from ferries and lighters and the bottleneck was broken, Since its inception, Port Authority bridges and tunnels alone have been used by 250,000,000 trucks and motor cars carrying passengers and merchandise between New Jersey and New York. As an average ferry crossing takes fourteen minutes and an average tunnel or bridge crossing four minutes, the resulting cumulative time if saved by one person would total 47 1/2 centuries, enough for a person traveling 30 miles an hour to make seven round trips between the earth and the sun. Tolls paid by drivers during the past year on Port Authority crossings exceed $15,000,000. Increased efficiency has been due to the employment of labor-saving mechanical devices. The Port of New York has more modern freight-handling machinery than can be found in any other three salt-water ports in the United States. The port’s heavy lift equipment includes many fixed cranes, a fleet of derrick lighters and gigantic floating cranes. Floated direct to shipside, one derrick has lifted such monster items as sixteen-inch coast-defense guns - one hundred sixty-five tons poised in perfect balance; a sixty-ton steel bridge girder, and a complete oil storage tank without dismantling. Four derricks lashed together have transported a bank of thirty-six conduit pipes, almost a block long. Pier loading mechanisms include tractors, power-driven lift trucks and lumber carriers which move along the piers and shuttle back and forth between shipside and transit sheds and warehouse. Many units are equipped with prongs, forks and small hoists, to lift special types of cargo. Like motor trucks on land is a flotilla of local harbor boats which speeds shipments between the various areas. These barges, scows and lighters are like heavy-duty water trucks delivering fuel, building supplies and general merchandise. Functioning like the horse on land are six hundred husky tugboats which tow lighters, barges, carfloats and other floating equipment not self-powered. Some seventy-five tugs move from pier to pier, maneuvering liners in and out of their berths. Many have two-way ship-to-shore radio. The tug fleet includes Diesel electric-operated, streamlined, modern craft. For the handling of valuable cargo and other non-bulky commodities are fast self-propelled lighters, which need no tugs Equipped with derricks, these lighters load or unload at shipside and carry cargos to rail connections, assuring a quick inter- change of goods between land and water. Strangely, the port, which is really a number of ports, has tended to specialize according to locality. Each of the eight large bays, Jamaica, Upper, Lower, Raritan, Gravesend, Newark, Flushing and Eastchester has a distinct character of its own. So have the four rivers, Raritan, Passaic, Hackensack and Hudson and the four straits, Harlem River, East River, Arthur Kill and the Kill van Kull. In several of these waterways ports like Antwerp and Hamburg could be hidden away and hardly noticed, yet none is a complete all-purpose port in itself. At Port Newark, 45,000,000 board feet of lumber are unloaded per month and warehouses can store 10,000 fully loaded freight cars. This is a center for the rail-to-keel service of four large railroads. Shipbuilding is Kearney’s specialty and 10,000 men worked in its yards before the war-time emergency grew to its present size. Bayonne has a drydock large enough to lift the largest naval vessel ever constructed. It also has the largest concentration of oil refineries and storage tanks in the East. Hoboken is the base of some of the nation’s largest lines of freighters, including seagoing car ferries which ply to Havana, New Orleans and Texas City, where fully loaded freight cars are lifted from the holds of the ships and set down on tracks to continue to their destinations. Staten Island has long been known as the terminus for products from the far East. It is also a shipbuilding center and, since the emergency, loads huge quantities of war-zone cargo. The Bronx acts as a feeder to the Island of Manhattan with power plants, coal depots, asphalt works and gypsum plants. And finally there is Brooklyn which handles nearly one-fourth of the entire traffic volume of the port with 34 steamship piers, 8,000,000 square feet of storage and industrial space on its docks and its own waterfront railway. Behind the waterfront are more than 100 more storage buildings. And still there is room for one of the world’s great navy yards. Typical of the precautions being taken to guard this “gateway to the world” is the daily minesweeping operation. Fleets of stubby little vessels ply back and forth, searching the harbor for explosives that some enemy warship might have laid. In addition, there are numerous devices designed for protection of the harbor against hostile submarines and other craft.