-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Who is Yehudi?

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Who is Yehudi?

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

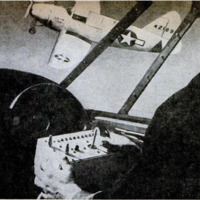

A WAR-WEARY Flying Fortress stag-

gered off an Eighth Air Force airdrome

with the heaviest war load ever lifted by

this type of bomber. It carried only enough

fuel for a one-way trip, a pilot, a copilot,

and a device they called “Yehudi.” This was

the take-off of the top-secret, joint Army-

Navy “Anvil Project,” and the beginning of

one of the war's weirdest air missions.

After the climb to its cruising altitude,

the explosive-filled Fortress was abandoned

by the two pilots, who parachuted safely to

British soil, leaving the bomber in the hands

of “Yehudi”—the little man who isn’t there.

Guided by his invisible hands, the B-17 flew

in perfect formation with the accompanying

Fortresses and escort fighters out over the

North Sea for nearly three hours.

Flak became heavy as they approached

the vital German naval base on Helgoland.

The Forts and fighters climbed several

thousand feet higher and took evasive

action. None was more evasive than that

lone B-17 with the empty cockpit away

below. Suddenly it stopped its weaving in

flight, made several turns in a steep, glid-

ing spiral. Then it dived straight toward

the submarine installations on Helgoland.

The German gunners never got it on the

way down. And they never got that sub

yard back into operation. Concussion waves

from the explosion bounced the escorting

planes at their 30,000-foot altitude.

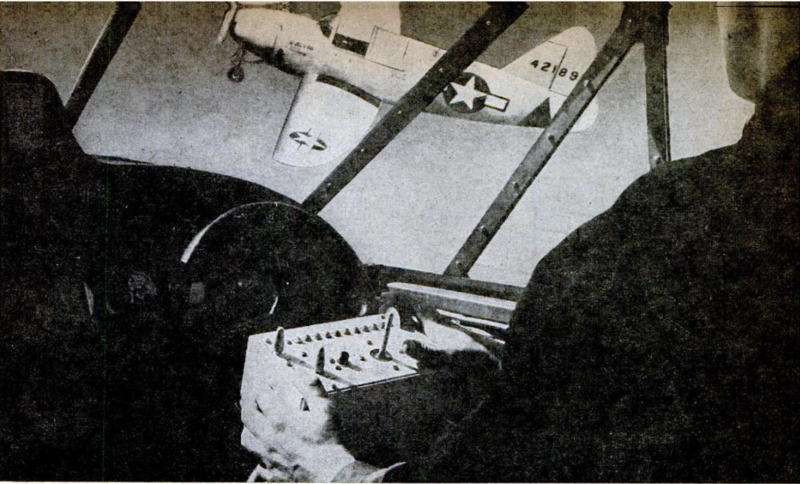

The push-button warfare continued from

early in 1944 until the very end of World

War II, as war-wearies were crammed with

TNT and a new explosive, which is still

secret, and sent plunging, by remote control,

into a number of German and Japanese

high-priority targets. On each mission an

officer on special duty from the Air Tech-

nical Service Command's Equipment Labo-

ratory—one of the AAF’s most secret in-

stallations at Wright Field—rode in the

copilot’s seat of one of the accompanying

bombers. He carried in his lap a small

aluminum box with which he sent radio

commands to “Yehudi,” a combination radio

receiver and automatic pilot in the con-

trolled plane.

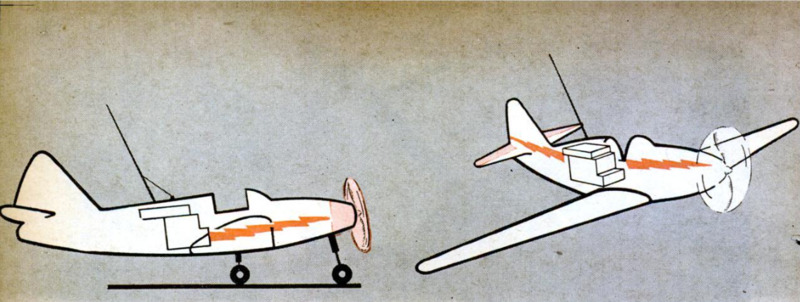

Smaller pilotless craft have been used as

ground and aerial gunnery targets for more

than three years. And the art of radio

piloting has progressed to the point where

“Yehudi” can now replace the pilots of jet

planes and carrier-based Hellcat fighters, or

the test pilots who normally fiy untried,

experimental craft.

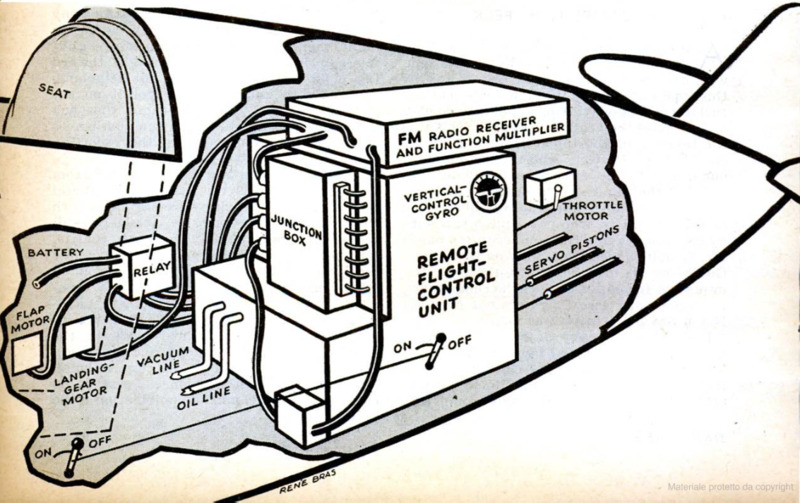

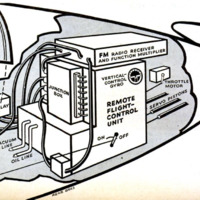

This miracle of radio piloting is accom-

plished through the use of an aluminum

“stick box” which is fitted with a miniature

control stick, switches, and indicating lights.

A cable connects this with the FM radio

transmitter and its five-foot, half-wave-

length whip antenna that sends the com-

mands to the 10-channel FM receiver in the

controlled plane. The radio impulses then

go through a “function multiplier” box

where they are “decoded” and passed on to

the remote flight control unit (RFCU)

Here they are translated into motion for the

working of the plane’s controls by means of

hydraulic pistons. ?

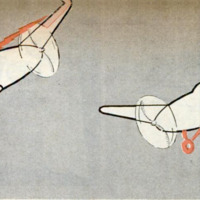

You don't have to be a musician to be a

good radio-plane pilot, but it helps. There

is a balanced modulator in the transmitter

hookup that produces eight musical tones

which can be heard through headphones

worn by the operator. Hach of these de-

notes some movement of the plane's con-

trols. Each of the eight amber lights on the

stick box also glows to the tune of some

control function, but the lights are seen

before the tones are heard. When the “turn”

light glows, for example, this indicates that

the circuit is clear for turning action. The

operator hears no tone until he moves the

little stick and the plane begins to turn. The

order is given with the light, and the

“execute” command with the musical tone.

Expert radio-plane pilots rarely wear the

headphones while the plane is within sight.

Really “hot” operators do not even watch

the lights, but concentrate on the controlled

plane itself. Only rated AAF or Navy flyers

are recruited for this musical flying duty,

and it takes an experienced airman about

50 hours to learn how to be a “beep pilot.”

There is no “feel” to radio flying; it is

strictly a matter of air judgment and

finger facility. A safety pilot rides in the

controlled plane to correct the student's

mistakes, and an automatic power valve

enables him to

override the RFCU control action at any

time. Trainees begin their radio flying from

ground stations and fly from a mother

plane during the advanced stage.

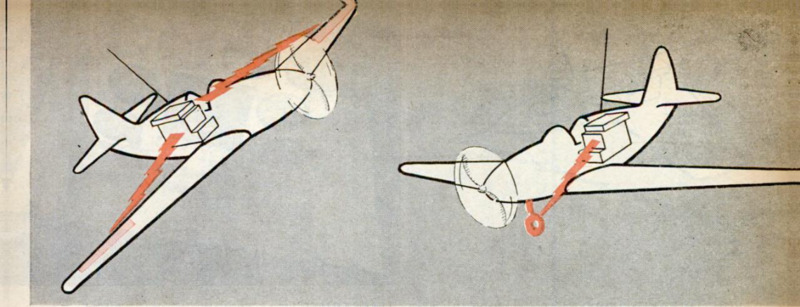

The flight-testing of mew experimental

airplanes is one of the newer and more

imaginative applications of radio piloting.

Particularly dangerous maneuvers such as

power spins and terminal-velocity dives,

from which a plane might not recover, can

now be carried out under radio control from

a mother plane or ground station.

The reason for putting a new plane

through these maneuvers is to find out how

it responds, or doesn’t respond, and why.

The instrument readings of a plane under

test usually furnish most of this informa-

tion. Pilots and technicians of the Air

Technical Service Command, Bell Aircraft,

and other commercial firms collaborated a

few months ago in the development of

the YP-59B Airacomet jet fighter. The test

jet is called the “Reluctant Robot.”

A specially equipped mother plane, an-

other Airacomet called the “Mystic Mis-

tress,” is used as a mother plane, and is

probably the only two-seater jet fighter in

America. It can be distinguished from any

other YP-50B jet by the long, swordlike

antenna protruding from the nose and by

the extra cockpit in the cowling ahead of

the regular pilot's cabin. A flight engineer

or observer rides in this extra seat. Instead

of the conventional stick box holding all the

necessary controls, the “Mistress” has the

miniature control stick set into the handle

of the regular pilot's control stick. The

function switches and their indicating lights

are installed in an extra-large handle on

the jet plane’s throttle.

Thus, in putting the “Reluctant Robot”

through its paces, the mother-plane pilot

flies both his ship and the “Robot.”

The instrument readings are televised,

passed on to the transmitter in the test

plane's nose and sent down to the ground

or to the mother plane. Here, the observers

can read the test plane's instruments on a

television screen as well as if they were

flying in the “Reluctant Robot" itself.

Wright Field pilots say that radio-con-

trolled aircraft can now be used for any

purpose piloted planes can fulfill. Although

passengers can hardly be expected to be

intrigued by the idea of flying in pilotless

airliners, there are many other uses to

which “Yehudi” can be put. In war and

peace, he has proved himself a pretty in-

telligent robot.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

James L. H. Peck (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-12

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

93-95,224

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 6, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 147, n. 6, 1945