-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

What is the outlook for aviation in 1941?

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: What is the outlook for aviation in 1941?

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

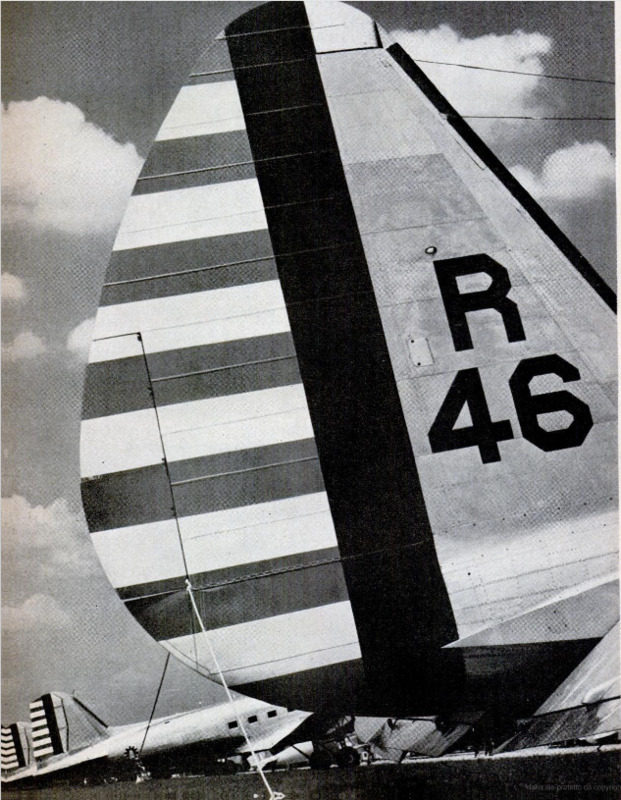

PRESENT indications point to 1941

as a boom year in American avia-

tion. On both the military and

civil aeronautical fronts, prospects

could scarcely be brighter—thanks to

factories glutted with British war

orders and American national-defense

contracts and to the Civil Aeronautics

Administration's pilot-training pro-

gram in the universities and colleges.

The warplane building program is

scheduled to go on at ever-increasing

tempo until the second quarter of 1942.

By that time, the National Defense

Advisory Commission estimates, the in-

dustry will have produced (since July 1,

1940) some 19,000 aircraft for our own

Army and Navy, plus 14,000 for the

Royal Air Force; simultaneously, it will

have built up its production capacity

to the point where it can turn out fight-

ing planes at the rate of 50,000 a year.

Whether there will be a continuing

market for any such production, at

home or abroad, is a question the ex-

perts seem willing to leave unanswered

until 1942. Actually, the combined air-

craft requirements of the Army and

Navy, as presently conceived for West-

ern Hemisphere defense purposes, is

less than half the 50,000 airplanes

envisaged by President Roosevelt in

his “total defense” message last May.

The C.A.A. program lays claim to

no military significance beyond that of

creating a reservoir of air-minded

youth, trained in the rudiments of fly-

ing, from which the Army and Navy

can draw candidates for their special-

ized training. This is mo longer a

“civilian theory”; it already has been

transformed by the demand for mili-

tary pilots into an everyday fact and

one which seems to be working to the

great satisfaction of the two services.

Likewise, the Army appears to be well

pleased with its now well-established

system of contracting with civilian fly

ing schools to give the majority of its

air cadets their primary training.

This experiment, and the far more

comprehensive one of the C.A.A. in

carrying out its pilot training program

through the existing facilities of civil

aviation—the struggling flying-service

operators on thousands of airports all

over the country—have been a tre-

mendous boon to the industry. What

is more, they may be the means of its

salvation in the inevitable let-down

days ahead when the present “emer-

gency" passes, when the expanding air-

craft factories of today come to an end

of their war orders and a tapering-off

of their defense contracts. Perhaps,

when that time arrives, the thousands

of young men and women whom the

C.A.A. has taught to fly will constitute

such a market for civil aircraft that a

thriving industry can be kept alive

without the stimulus of abnormal mili-

tary buying.

" WE HAVE big orders and we are get-

the the materials we need to fill

them. We are expanding our plant, install-

ing new machines, training new workers.

All the other airplane manufacturers are

doing the same thing. Mass production will

become a reality just as soon as these new

facilities can be put to work. And with

mass production we'll get the job assigned

us done on time.”

That's the way the aircraft-production

situation looks to an official of the Glenn L.

Martin factory, Baltimore, Md.—a man who

is on the industry's firing line in its battle

against time to build up our inadequate air

defenses. How does it look in Washington,

G.H.Q. of the colossal defense program?

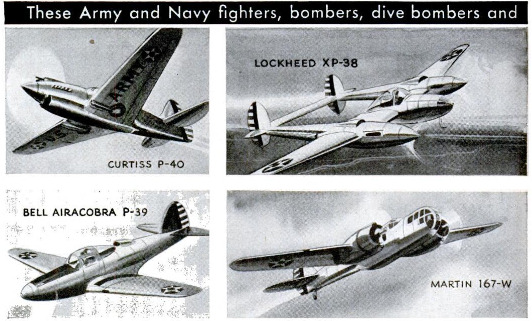

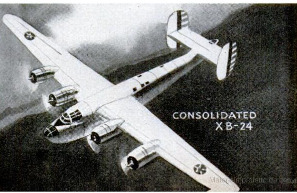

Right now the country’s aviation experts

are devoting all their time to turning out the

33,000 bombers, dive bombers, and pursuit

ships—19,000 for our own Army and Navy

and 14,000 for Great Britain—which they

have estimated American factories can pro-

duce by April 1, 1942.

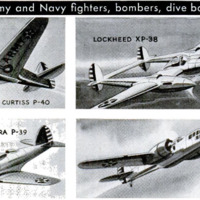

Plant expansion, financed wholly or

in part, directly or indirectly by the

Government on terms which protect

the manufacturers against loss when

the present emergency is over, is go-

ing ahead. The Curtiss-Wright Cor-

poration is building new plants near

Columbus and Cincinnati and is en-

larging its Buffalo, St. Louis, and

Paterson, N. J., factories. Similar

expansion has been accomplished and

is still under way at United Aircraft

Corporation's Pratt & Whitney engine

and Hamilton Standard propeller di-

visions, in East Hartford, Conn., and

at its Vought-Sikorsky airplane di-

vision at Bridgeport, Conn. The

Martin company is increasing its floor

space from 1,350,000 square feet to

almost 4,000,000. North American

Aviation is supplementing its Los

Angeles plant with a new one in Dal-

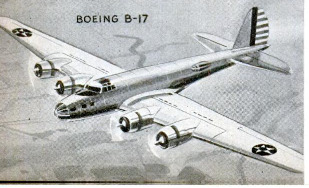

las. Douglas, Boeing, Consolidated,

Lockheed, Vultee and all the other

companies are making planes for the

Army and Navy.

Building aircraft engines is a more

complicated job than turning out the

airplanes themselves, and engine pro-

duction cannot be increased with the

same rapidity as that of aircraft. Al-

ready the public has seen the spec-

tacle of combat planes coming off the

production line days and weeks ahead

of the engines to be installed in them;

of motorless Curtiss P-40 pursuit ships

collecting under circus tents and other

temporary shelter at Buffalo, waiting

for their Allison engines; of Boeing

flying fortresses cluttering up the air-

port at Seattle waiting for Wright

Cyclone motors, or being stripped of

their power plants after flying to an

Army field so that the engines could

be taken back to the factory and in-

stalled in a succeeding bomber.

Seen in flight, the modern military

airplane has a look of sleek simplicity,

yet it is one of the most complicated

weapons man has ever evolved. Its

14,000-0dd parts come from several

hundred different sources of supply;

the knowledge and skill of scores of

sciences and crafts go into it.

In the Martin plant, after the de-

sign of a new plane is approved, it is

drawn out, full size, on coated alumi-

num-alloy sheets. When every detail

is complete, the sheets are photo-

graphed by a huge camera of special

design, which is later used as a pro-

jector to reproduce the drawings, full

size or to any desired scale, on any

material.

Tool-design engineers decide on the

machine tools and dies needed to

make the plane's many parts. Dozens

of special machines cut and bend

metal into the shapes called for by

the drawings. A metal-stretching

press forms the whole belly of a bom-

ber fuselage over a wooden pattern in

a single quick operation—it would

take two men six hours to do that job

by old, bumping hammer-and-file

methods. A big router shapes out a

dozen sheets of duralumin at a time.

Airplane-factory assembly lines do

not move in the continuous fashion of

automobile assembly lines, but rather

by stages. The standards of work-

manship are too high and the stake of

human life too great for the speed of

automobile production.

As parts move from stage to stage

on the production line they are joined

together in sub-assemblies until at

last they become wings or tails or

nose sections. For the sake of acces-

sibility, the whole front end of a bomb-

er fuselage is built in halves, with con-

trols and other interior fittings in-

stalled, and these halves are then

riveted together. As the various sec-

tions of the plane near completion,

they converge in a final assembly line

and are joined together as a complete

ship. The engines are then installed,

fuel and oil lines and electrical wiring

are hooked up, controls are connected,

and the airplane is ready for flight.

The job of supplying the United

States and its friends with 3,000

planes a month is a prodigious one,

yet “Big Bill” Knudsen, the Defense

Commission's production codrdinator,

believes that it can be done. He has

inspired the confidence of the entire

aviation industry by cutting red tape

and eliminating lost motion, until

now even the industry's professional

pessimists see light ahead.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

C. B. Allen

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

72-75

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 1, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 1, 1941