-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Canada rallies her cat man: North woods tractor drivers summoned to run war tanks

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Canada rallies her cat man: North woods tractor drivers summoned to run war tanks

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

FIFTY degrees below zero, a blizzard

blowing, and 200 miles to go. Over froz-

en muskeg bogs, down creek beds, and

up through the bush over rugged moraines

go the drivers of the tractor trains, all

through the wild Canadian winter, freight-

ing machinery and

supplies to the new

gold mines of the

northern canoe coun-

try.

For this kind of

mushing, which in

recent years has

conquered the

swampy wilderness

for heavy traffic, a

man has got to be

tough. But especial-

ly he’s got to be

good. That's why

he’s sure to make a real tank soldier.

The far north's new breed of musher is

called a cat-skinner. Up around God's Lake

and Hudson Bay there aren't so many cat-

skinners this winter. They've been joining

the Canadian Army in droves, and as soon

as they can get a proper rig of machinery

they are figuring on starting for Berlin.

After all, a tank is nothing but an over-

grown, armored cat—with some teeth in it.

At his peacetime job, the cat-skinner

rides the cab of a six-ton Caterpillar tractor

over trails marked by poles in the drifted

snow, with six sleds and a caboose behind

and maybe fifty tons of precious freight.

On his cat he carries a spare radiator and

six barrels of gas. He uses fuel oil for anti-

freeze and he keeps his engine running for

five or six days at a stretch. If it breaks

down on him, he rigs a tent over his cat,

installs a stove, takes a chew of tobacco

and a monkey wrench, and fixes things right

on the spot. When he starts out with a cat

train, he gets there and he brings it back.

You'll find these north-country men today

in a sandy wilderness of tar-paper shacks

called Camp Borden, up between Lake Sim-

coe and Georgian Bay, north of Toronto—

tinkering with those 200 World War tanks

which the U. S. Army sent to Canada a few

weeks ago.

‘With them are cat-skinners from the

western construction crews, drag-line men,

clamshell men, bulldozer

men. And hundreds of boys

from the farms of Manitoba

and Saskatchewan, who

know their gas engines and

Diesels too. If a lad is trac-

toring a section of wheat

land twenty miles from the

railroad, he can’t call the

garage when something

goes wrong. And when that

lad goes to town, he drives

his own jallopy.

One look at those old

tanks we sent to Canada

would give Hitler a belly

laugh, but another look at

the men who are handling

them would tone it down.

Just let the R. A. F. and

London hold out long

enough for the tank fac-

tories to get going, and the

Panzer divisions will have

something to tangle with.

Take the Fort Garry

Horse, for instance. That's

a cavalry regiment from

Manitoba, named for the

old frontier post which be-

came Winnipeg. In the last

war it dashed behind the

old frontier post which be-

came Winnipeg. In the last

war it dashed behind the

lines and put a German

field battery out of action,

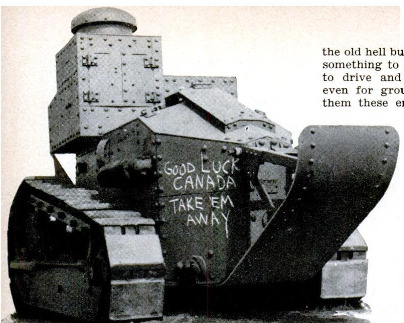

the old hell buggies were, they gave the men

something to work on, a means of learning

to drive and navigate cross-country, and

even for group maneuvers later on. With

them these empty-handed regiments could

‘be turned into going concerns.

Bright and early the Fort

Garry horsemen were on hand

at the depot to get their

quota of forty tanks. Experi-

enced tank men, there to

show the troopers what to do,

just stood by with surprised

looks on their faces. The

cavalrymen hitched up a few

hose connections, poured a

little gas ih the vacuum

tanks, twisted the cranks,

climbed aboard, and simply

drove the cats away.

“Ride 'em, cowboys!" some-

body cried—and they did.

These little six-ton, two-

man tanks (American-made

on the Renault model) were tough-look-

ing babies, weathered for more than

twenty years in a parking lot at Fort

George G. Meade in Maryland, many

of their hulls and turrets pitted with

machine-gun marks, presumably from

the last war. They clattered along on

wide steel plates with heavy lugs (a

far cry from the flexible chainlike links

of speedy modern tracks) which slapped

on the ground and limited speed to six

miles an hour. But the engines and

running gear were O.K.; they had been

greased up well when put away. And

if the old-style tracks were good for

only 150 miles on these sands at Camp

Borden, that was fine. So much more

repair work to be done in the winter.

Back at their own quar-

ters, the Fort Garry boys

went to work. Within

three days, twenty-five of

those forty tanks were out

in line, purring like kit-

tens, and the rest were

well on the way.

The boys clattered up

and down in the open

spaces among the bar-

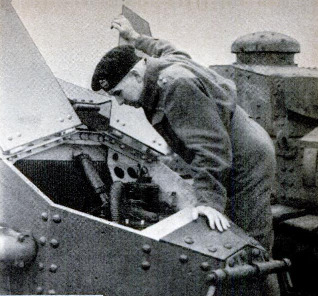

racks. For a man who has

driven a car there are only

a few things to catch onto.

The controls are almost

the same as a car's, except

that you practically sit on

the floor and instead of a

wheel you have two clutch

levers, one for each track.

Pull back the right lever,

it disengages the clutch of

the right tread and turns

you in that direction. Un-

like most cats, a still

harder pull brakes the track, and you make

a hairpin turn. It is in rough country that

the cat man's skill comes into play. There

the novice can easily tip over a fast tank,

perhaps kill his passenger if the turret

above is open. But the experienced man will

instinctively spin her when she tips, quickly

turn her nose straight down the grade.

Anyway, the boys took to the equipment

like ducklings to a mud puddle. And old

horse soldiers happily realized something:

the Northwest still breeds good horse riders;

but the same lads are part of a whole gen-

eration which has grown up in North

America since the last war, a generation

which practically cut its teeth on a spark

plug and was weaned on a carburetor.

‘That is something worth remembering in

these gloomy war days. Since the disasters

of last May, all of us have been centering

our thoughts on aviation, on assembly lines,

machine tools, and crafts-

men who can split a thou-

sandth of an inch. These

things are all important,

and military aviators have

to know their trigonom-

etry. But when armored

vehicles are produced, it's

going to be the back-yard and the back-

country mechanics who fight with them. If

Britain is to win, there will be more war on

the continent. And whether they take off

from the Near East or from a beach-head

on the Channel, that's when you're likely

to hear more of Canada’s cat-skinners, and

of their salty, peppery, pint-sized com-

mander, Col. F. F. Worthington.

This is one of those sad, pathetic tales

of unpreparedness, though it now may have

a satisfactory ending. Worthy, as they call

him all up and down Canada, was his coun-

try’s bug on mechanized equipment, one of

those prophets without honor which every

country seems to have. The United States

had Billy Mitchell, France had De Gaulle,

and quite possibly in Germany today there

is some ignored seer telling Hitler why he

is going to lose the war.

‘When the first World War broke out,

Scottish-born Worthington was a young

adventurer in Central America—ship’s

engineer, mining engineer, and ma-

chine-gunner. Fresh from fighting

against Villa for Madero, he went up to

Canada and enlisted in the Black Watch.

In France he was four times decorated

for deeds which he will now describe

only as “self-preservation.” He wound

up the war as a captain in one of the

world’s pioneer armored-car outfits,

known as Brutinel's Brigade.

Gen. Raymond Brutinel was a French

engineer, living in Canada, who early

in the last war foresaw the coming of

armored, mechanized warfare. His idea

was so outlandish that his outfit had

to be equipped by private subscription,

with guns obtained in various ways,

sometimes illegal. Its original equip-

ment was a two-cylinder Autocar truck,

with a steel box built around it, mount-

ing two Colt machine guns. When the masses

of British tanks broke through the line

on August 8, 1918, which Ludendorff called

Germany's blackest day, Brutinel's Brigade

came close behind, with machine guns on

trucks, motorcycle side cars and trucks.

The battle plan for that day followed pre-

cisely the tactics used last June by the

German armored divisions in France. Bru-

tinel's column was to have dashed through

and grabbed Roye, a rail center. But the

battle that was visualized never quite came

off, because the higher command was wor-

ried about protecting the flanks.

“But that was a tank battle, identical

with what the Hun has done now,” Colonel

‘Worthington recalls today. “We showed the

bugger the way. It boils me up. It's almost

a shame he didn't have more tanks then,

so we'd have remembered.”

WORTHINGTON remembered the!

ome When Canada after the war

became even more demilitarized than the

United States, he stayed on with the skele-

ton army, waiting for the war he knew was

coming. Worthy was a very popular fellow,

but was always talking tanks and mecha-

nized warfare. Kind of eccentric on the

subject. Or so people thought.

Four years ago the Canadian Army es-

tablished a “tank school” with Worthington:

in command. In the spring of 1938 he set up,

in a few shacks in the deserted sands of

Camp Borden, the Canadian Armoured

Fighting Vehicles Training Centre, C.A.S.F. |

With the beginning of the war, groups of

officers and men from tank regiments of

the active militia were rushed in for train-

ing in tactics, radio, gunnery, and driving

and maintenance, so they could go back to

their own outfits and pass on the knowledge.

Even so, lack of equipment made it neces-

sary to do much training with gadgets sub-

stituting for the real thing. Most ingenious

of these is a device called a “rypa,” a turret

which jolts and pitches like the jouncing of

a tank, from which the gunner shoots air-

rifle pellets down a sand-pit range.

The lowlands blitzkrieg of last May sud-

denly brought to Canada the realization

that it had done hardly anything about tank

warfare. Tank building got under way al-

most immediately, in the Canadian Pacific

Railway shops. Nothing is being said about

when the new tanks will be delivered, or

what they will be like. But a contract was

recently let for nine carloads of pins for

caterpiller tracks.

‘Well, I went up to Camp Borden to find

out what in the world a nation at war

wanted with those old World War clunks,

and this story is what I found out. It is a

Canadian story, but in many ways it might

be a story of the United States, too. Our

armored vehicles are also on order, and in

army maneuvers we use ice trucks. But

then again we have our own cat-skinners,

and our lads from the mechanized farms,

and the boys fixing their flivvers in the

back yards—millions more of them than

Canada. A lot of them will be getting to-

gether in barracks this winter, eager for

machinery to work with. And it begins to

look as though, in due course, they will be

getting it.

At any rate, once the present excitement

about production is over, we are going to

realize strongly that there is a lot more in

preparedness than machine tools. We're go-

ing to realize that the used-car lot and the

despised jallopy are among the strongest

links in our national defense. You can learn

a lot from an old piece of machinery.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

76-80

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 1, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 1, 1941