-

Titolo

-

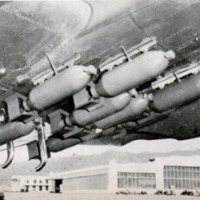

Air defense -1941 style

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Air defense -1941 style

-

extracted text

-

Those of our citizens who are having the

jitters about possible mass bombings of

American cities from the air, or who fear

outright invasion, should take a sedative

and survey the situation from the stand-

point of those who are to do the bombing

or invading. We cannot be attacked by tele-

vision, fortunately. We can be attacked

only by an enemy who possesses the physi-

cal means to span several thousand miles of

ocean and carry out his design. How is he

going to do it?

He cannot fly over from Asia or Europe

directly. For the present, there are no mili-

tary planes, in numbers worth considering,

capable of crossing, dropping bombs, and

returning home. That sort of thing is on an

experimental basis, as yet. Some of the

experts assure us that such bombers will

be an aeronautical commonplace in five

years, perhaps less. If they are right, our

air-defense problem will become far more

difficult in the future. But we have time to

get ready for that situation. As an imme-

diate possibility it is out.

This reduces the means of direct attack

to surface ships and airplanes operating

from surface ships, and brings the United

States Navy into the picture. The Navy is

prepared for any immediate eventuality.

Early this year a clear-headed American

army officer wrote in one of the technical

military journals, “The Navy is always

ready for war, the Army never.” That is

true in the air as well as on land and at sea.

It is no particular credit to the Navy, and

reflects no discredit whatsoever on the

Army. It simply expresses the fact that for

a country situated between two oceans, the

Navy is necessarily the first line of defense.

It was planned that way and the principle

remains sound.

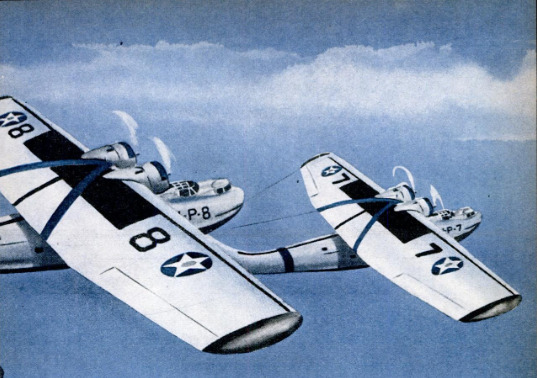

Most Americans know that the Navy has

a first-rate air arm—the newsreels tell them

that much—but very few know that our

naval air force is not only one of the best,

but the largest in the world. The totalita-

rian brethren know it, though, even if our

citizens don't. This naval air force, even

without the support of the Army's heavy

bombers, could make the high seas very

unhealthy for any foreign expeditionary

force which ventured thousands of miles

from home to attack the continental United

States. Perhaps our patrol bombers and

flying fortresses can't send capital ships

with heavy deck armor to the bottom, but

they can certainly send them into dry dock,

back where they came from. The invaders,

as long as bombers are confined to their

present ranges, will not have the where-

withal to inflict the same punishment on

our ships.

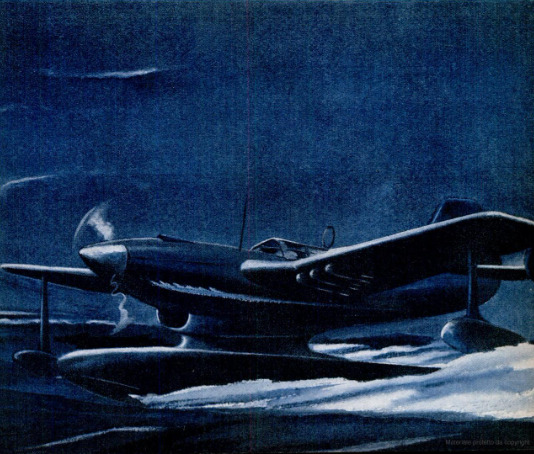

Aircraft carriers? Yes, but an aircraft

carrier does not transport many heavy

bombers, and is itself in danger of being

sunk by a single large land-based plane, or

a seaplane operating from a tender. Nobody

has very many carriers, and a navy is about

as willing to risk them in enemy waters as

—well, as the British were in the Norwegian |

campaign, and that was only across the |

North Sea. We have seven carriers our-

selves, two of them old but modernized, one

six years old, the rest new or practically |

new, and their 500-odd planes can keep a

sharp eye on a lot of ocean and do some

light and medium bombing on the side.

Indirect attack offers better possibilities

for sustained air assault on American ob-

jectives—the only kind which has military |

significance. This would entail the estab-

lishment of an air base or bases in the |

Western Hemisphere from which large

numbers of bombers could take off for the

Panama Canal and the United States.

Granting that all the ships the totalitarians

could detach, plus a good part of the British |

fleet if it fell into German hands, would still |

be incompetent to challenge the American

Fleet in its home waters, such an armada |

might make a landing in South America,

which is not home waters for us either. But |

the venture is not one to be gone into |

lightly. A foreign expeditionary force can-

not be sneaked across to the Americas.

Three divisions, about 50,000 men, would

require almost 400,000 tons of shipping be-

sides the escorting force. And that would

be only a beginning. Once the army was

landed, a minimum of 700,000 tons of ship- |

ping would be required monthly just to sup-

ply them, and they would have to be sup-

plied very well to carry on their aerial op-

erations to the north. Nor would they be

unmolested during the preparatory period, |

for where Pan-American airliners go, long-

range bombers can go likewise. |

But let the worst come to the worst: |

assume that the Canal is blocked before the |

third set of locks can be installed, and that

with the bulk of the Fleet isolated in one |

ocean, the other coast must rely entirely on

its shore batteries, antiaircraft artillery,

and aviation. The theory of cobrdinated

naval-and-air defense for America would

then rest more than ever on the massive

use of the bomber against invaders by sea

and air. And if all this happened before the

end of 1941, while we were still short of

bombers for such an extremity, what then?

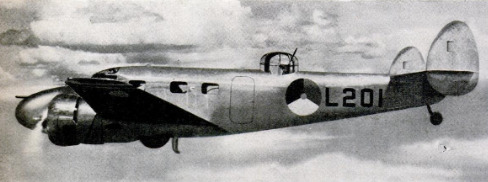

A suggestion that is frequently made in

this connection is the conversion of com-

mercial planes into bombers. The United

States leads the world in commercial air

transport, and our factories are equipped to

manufacture bombers of the same basic

design, carrying T.N.T. instead of passen-

gers. In some quarters it is asserted that,

stripped and souped up, such improvised

bombers could fly 300 m.p.h. at 20,000 feet,

and their operating radii would be 1,500

miles with 1.5 tons of bombs, or 1,000 miles

with two tons. Service flyers differ with

these estimates and point out that combat

aircraft should be originally designed and

built to withstand stresses and loads which

are not encountered in commercial flying.

“You can't merely hang a bomb rack and a

load of bombs on a DC-3 transport and have

a military bomber,” as one prominent naval

aviation officer puts it.

To a detached observer it looks as if both

sides were right and that they are talking

of different situations. Army and navy men

nowadays are technicians, and they take a

technician's pride in machines—their ma-

chines. Without such a feeling they would

be no good as technicians or fighters. More-

over, the officers who do the planning want

to be assured that the planes in which other

men are to do the flying are the best ma-

chines that engineering can produce and

money can buy. That also needs no justifi-

cation. But in an emergency such consid-

erations must go by the board. In that case

a few hundred or even a few thousand us-

able if by no means perfect bombers might

be a sample of Yankee practicality on the

order of the Nazis’ feat in pouring out

planes with short-lived engines and a mini-

mum of instruments—planes that were far

from a technician's dream, but that were

ready when the Nazis needed them.

There may be no emergency of this kind.

At the moment it seems remote. But while

the drafting and tooling for the de luxe

bombers is going ahead, the conversion idea

should be put to the test—just in case.

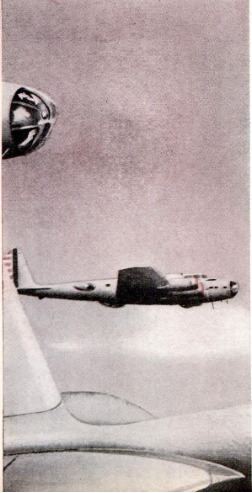

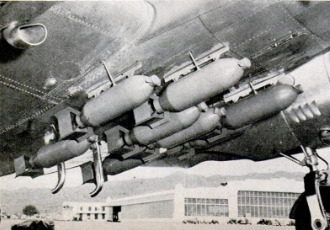

It cannot be too strongly emphasized that

the long-range bomber, coordinated with

naval operations, is the key to American

air defense. We have on hand about 1,500

army and navy bombers, roughly half of

which are in the medium and heavy class.

We shall have more of them long before we

can build our two-ocean Navy, long before

we can train a large Army. With an ade-

quate fleet of bombers we are in the posi-

tion of a prize fighter with a long reach and

great skill in boxing, matched against a

strong, stocky opponent who likes to clinch

and fight to the stomach. Why let him get

closer than we can help? The results of let-

ting him bore in are plain enough from

England's experience. If one must rely on

pursuit and antiaircraft guns to ward off

the bombers over the streets, one may fight

with superhuman courage—but the streets

will still be full of wreckage afterwards.

Against invading air fleets this is protection

which does not protect, and which can at

best win a stalemate, not a victory. The

comparison is even more to the point when

it comes to land operations. If we take ad-

vantage of the breaks which Providence

has given us on the sea and in the air over

the sea, we shall never have to use our

Army to resist invasion by actual fighting

on the ground. Its value in that respect will

be purely psychological and diplomatic.

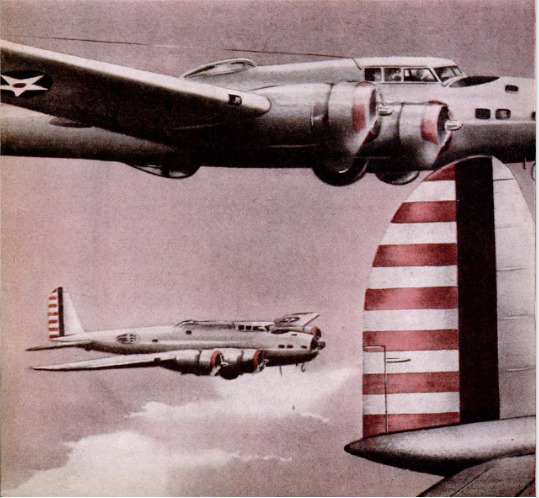

But in the air the Army's role is almost

as important as the Navy's. Army bombers

can fly over the ocean just as well as sea-

planes, and although the latter have the

advantage of operating from any point

where sheltered water and a tender are

available, the Army can in many cases per-

form long-range bombing missions with

equal efficiency. The Army also has the

enormously important responsibility of de-

fending the Navy's vital bases—in effect,

the Navy protects the country and the

Army protects the Navy at fixed points.

Far-flung bases are vital to the long-range

defense plan, and everything depends on

ability to hold strategic areas like Hawaii,

Puerto Rico, and Panama.

This is a big country, and the Army and

Navy together cannot guarantee 100-per-

cent security. There is no such insurance

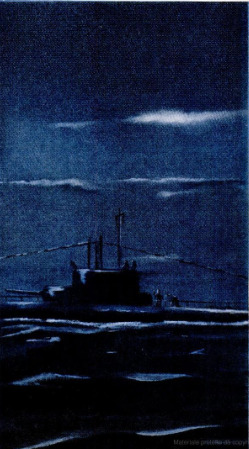

in war. If we get into the war our coastal

cities may be subjected to occasional hit-

and-run bombing raids. One or more small

or medium planes might be released from

a merchant vessel acting as a tender or

carrier, or even from a large submarine.

On a larger scale, an airplane carrier might

be sneaked to within a few hundred miles

of the coast; its planes could be released to

bomb cities at dusk, returning to the carrier

in darkness so as not to betray its position,

or the whole operation might be carried out

after nightfall. It would have little military

importance, but it would have scare value;

and that would be the object.

Such raids are difficult to cope with until

the mother ship is located and destroyed or

chased away. At least on the first attempt,

it is likely that bombs could be dropped.

After that an air patrol might intercept

the attackers during the daytime. At night,

however, pursuit defense is not very depend-

able. As bomber speeds rise pursuit from

the ground is at an increasing disadvantage,

even by day. With the bomber only 50

m.p.h. slower than the interceptor, an alert

factor of 15 minutes requires a 200-mile

warning if the defending plane is to meet

the attacker in front of the objective; even

with the best pursuit speeds and a shorter

alert factor, a 100-mile warning is the least

that will do. One cannot depend on getting

even a 100-mile warning from the sea.

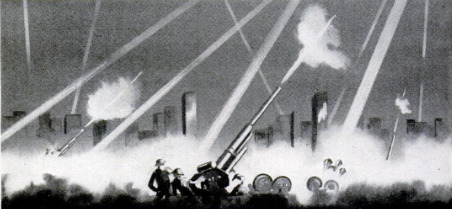

Under these conditions the importance of

antiaircraft guns to supplement pursuit

aviation in coastal defense is obvious.

And the guns have to be big. The Army's

experience with AA artillery illustrates the

difficulties of keeping up with the accelerat-

ed development of the art of war. Only a

few years ago, with slow bombers flying at

relatively low altitudes, the three-inch AA

gun was effective. But in those few years

the speed and ceiling of bombers more than

doubled. The problem now is to bring down

a 200-mp.h. plane at 25,000 to 30,000 feet.

The three-inch gun begins to peter out at

18,000 feet and above 20,000 it is practically

useless. The loaded bombers can fly 8,000

feet higher and still hit area targets. They

are too high then for point targets—but in

wartime nobody bothers much with little

distinctions like that. A point target be-

comes an area target if you don’t manage

to hit it.

Consequently the five-inch AA cannon is

now the Army's requirement. But that does

not mean that the smaller guns are obsolete,

either here or in Europe. The five-inch gun

requires an emplacement. Thus it is ideally

suited for the defense of the Panama Canal,

for example, but for general coast defense

the United States needs mobile AA artillery,

which can be concentrated at threatened

points on either coast, on the same theory

as defense by plane in the event that the

Fleet is unavailable by reason of obstruc-

tion of the Canal or other contingency.

That means 3.5-inch guns, like the German

88 mm., and 20 mm. (less than one-inch)

guns mounted on buildings and at emplace-

ments to protect the big guns.

AA defense by artillery and pursuit avia-

tion is necessary, for the same reason that

our prize fighter who prefers to box at

arm’s length must still be prepared to fight

at close quarters some of the time. But for

the United States it is secondary defense at

best. The primary defense remains the

Navy and defensive-offensive bomber opera-

tions by the Army and Navy in conjunction

with the Fleet.

Many people imagine that with the in-

creasing mechanization of war, men are no

longer important. The Army and Navy

know that the exact opposite is the truth.

As General Fox Conner puts it, “the en-

gineer of a modern express train must be

more highly trained and more intelligent

than a one-horse plow boy.” The training

of military airmen is as vital as the pro-

curement of sufficient planes and guns.

It is a much harder job now than in the

World War. At that time a man could be

trained on a Jennie and when he was sent

up in a combat plane there was no vast

disparity. Nowadays the difference in han-

dling between a primary trainer and a fast

pursuit ship or a big bomber is as great as

the difference between Sunday driving and

automobile racing. Pilots must be trained

in steps, and their training does not end

even after they have been flying with the

Army and Navy for years. And this is

equally true of mechanics, radio operators,

armorers, parachute riggers, and all the

other classifications.

American pilots are being trained in con-

siderable numbers under a comprehensive

program which has two principal objectives.

The first is to impound a large reservoir of

young men who can fly well enough to meet

the requirements for private-pilot-grade li-

censes. This part of the program is under

the direction of the Civil Aeronautics Ad-

ministration and training is given at col-

leges in the form of Civilian Pilot Training

courses. By June 30, 1941, 50,000 students

will have received instruction in the rudi-

ments of flight and a certain percentage of

these will constitute the raw material of

the expanded air forces. The elementary,

part-time training of the C. A. A. must not

be confused with the full-time flying courses

of the Army and Navy, given at Kelly Field

and Pensacola, respectively, with other

training centers being built to multiply the

pilot-producing capacity of the services.

The objective of the latter is to turn out

combat flyers equipped to continue their

training in army and navy operations.

The United States holds a tremendous

advantage in turning out pilots in that we

have an unlimited gasoline supply. Under

American pilots are being trained in con-

siderable numbers under a comprehensive

program which has two principal objectives.

The first is to impound a large reservoir of

young men who can fly well enough to meet

the requirements for private-pilot-grade li-

censes. This part of the program is under

the direction of the Civil Aeronautics Ad-

ministration and training is given at col-

leges in the form of Civilian Pilot Training

courses. By June 30, 1941, 50,000 students

will have received instruction in the rudi-

ments of flight and a certain percentage of

these will constitute the raw material of

the expanded air forces. The elementary,

part-time training of the C. A. A. must not

be confused with the full-time flying courses

of the Army and Navy, given at Kelly Field

and Pensacola, respectively, with other

training centers being built to multiply the

pilot-producing capacity of the services.

The objective of the latter is to turn out

combat flyers equipped to continue their

training in army and navy operations.

The United States holds a tremendous

advantage in turning out pilots in that we

have an unlimited gasoline supply. Under

our system a cadet in the military flying

course earns his commission as a second

lieutenant after nine months of training,

with 300 hours in ground classes and 215

hours in the air. After that he continues

to get instruction and experience with the

tactical unit to which he is assigned. No

other country can afford such expensive

preparation for its air service. To give

10,000 men 500 hours apiece in the air re-

quires 400,000,000 gallons of gasoline to

begin with. European countries haven't got

gas on that scale. Consequently they lose

flyers in combat who might have survived

if they had received more and better train-

ing, and they lose them in training for the

same reason.

We had the same experience in 1917;

many of us can remember the motto at the

Kelly Field of that day: “Fly or Die!”

That meant one a day for the undertaker.

The policy and its results are different now.

In the C. A. A. portion of the pilot-train-

ing program the fatalities are practically

negligible—around 110,000 man-hours in

the air to one fatality, and the majority of

the dozen or so fatal crack-ups which have

occurred have been the result of extreme

recklessness. In the service courses the

ratio of crack-ups is likewise low, largely

because utmost care is taken to weed out

accident-prone candidates and trainees.

Five out of six are rejected for physical or

nervous defects, and after that almost half

the survivors are washed out during the

course, the great majority in the elemen-

tary grade. The ratio of those who qualify

for actual military service is therefore

about 1 in 12. One can depend on it that

most of that 8.5 percent of picked men will

be pretty good material for the stupendous

job of organizing squadrons, groups, wings,

and air divisions on the scale contemplated.

I have already ex-

pressed the opinion

that this country is

safe from invasion if

we do not throw away

our geographical and

other blessings. Some

mistakes can be made

—but, as in any other

job, not too many. To

that end certain criti-

cisms of our air-de-

fense program are in

order.

1. In the first place,

it needs to be said

that the whole 50,000-

planes idea is a typi-

cally American sub-

stitution of bigness

and ballyhoo for in-

cisive technical think-

ing. We talk of 50,000

planes without speci-

fying what types, and what each type is to

be used for, or exactly how such a Gargan-

tuan fleet of aircraft will fit into the inte-

grated defense scheme. A digit with a lot

of zeros after it is no guarantee of national

security. We may merely be manufacturing

obsolescence. Fifty thousand planes can be

as wrong as fifty million Frenchmen.

2. The public should be taken into the

Government's confidence to a greater ex-

tent in regard to military planning, and

particularly in the air phase. Not legiti-

mate military secrets, of course: the Army

cannot be expected to advertise that it is

setting up a five-inch AA battery at Hemp-

stead and a pom-pom outfit on the R.C.A.

Building, nor need the Navy tell us the

precise measures it is taking to protect the

Panama Canal. But neither should the

broad ouiines of planning be left entirely

to the conjectures of columnists and com-

mentators. A great deal of good can come

out of the participation of the average man

in such matters, as it has in the past. In

the January-February 1040 issue of the

“Coast Artillery Journal” Major Thomas R.

Phillips wrote, “The air force that all admit

we need was forced on the Army by popu-

lar demand and congressional action, how-

ever little we may like to admit it.” That

is a patriotic and democratic attitude, and

it should be the rule rather than the excep-

tion among our military men.

3. We are not devoting enough time and

money to aeronautical research. Our mili-

tary planes are very good, but tomorrow's

wars are not going to be fought with to-

day's planes. The Germans planned their

present air force for support of a motorized

army and to bomb near-by objectives. The

planes are not outstanding in design or

performance, but they were designed for

exactly what they are doing and produced

with exceptional technical efficiency. If the

Germans are ever in a position to get after

us they will need different planes—and all

the indications are that they will have them.

Whether we shall be as well off is doubtful.

Germany has seven great centers for aero-

nautical research, each equivalent to our

excellent but overloaded National Advisory

Committee for Aeronautics laboratory, each

specializing in one portion of the field and

cobrdinating its investigations with the

others. Major Eliot is right when he says,

“To a modern air force, research is the very

breath of life.” The last thing we can afford

to do is to put almost all our energy into

profitable production and to give only inci-

dental attention to the aircraft of the future

and the knowledge which will create them.

The planes that will win the air wars of

tomorrow have to be designed today.

4. The more discussion of air defense the

better, but discussion is one thing and hys-

teria another. Some of our people are over-

wrought on the subject, to say the least.

Such a state of mind, when it becomes

widespread, is a definite military danger.

At the beginning of the Spanish-American

War our eastern seaboard cities were in

such mortal fear of the pitiable Spanish

fleet that for some time our battleships had

to be kept inshore to “protect” the popula-

tion. Certain newspapers were responsible

for this exhibition, which one would like

to forget if it did not teach a lesson for the

present day. A few months ago one of our

leading magazines, which boasts that it has

20,000,000 readers, printed a lurid sketch

-

Autore secondario

-

Carl Dreher (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-02

-

pagine

-

73-80

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik