-

Titolo

-

Ready to roll transportation organizations to meet defense needs

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Ready to roll transportation organizations to meet defense needs

-

extracted text

-

TROOPS and tanks, planes and bombs,

Tem and ammunition are all mighty

words in the language of the defense

program of the United States. But mightier

than all of them is the key word: “Trans-

portation.”

That is why President Roosevelt, in call-

ing upon leading industrialists to help co-

ordinate the nation's greatest peacetime

military effort, included a veteran railroad

man with a reputation for getting things

done.

Men, materials, and machines, the three

essential ingredients of modern military

power, are worthless unless the nation pos-

sessing them has a transportation system

capable of getting them where they are

needed at the time they are needed.

It is part of the task of the National De-

fense Advisory Commission to see that

America gets the most out of its railroads,

its highways, its air lines, its waterways,

and its pipe lines during the industrial mo-

bilization, and to plan just how all those

systems should function if they had to be

used during a conflict.

We have something to work with—no

doubt about that. This country has more

trains running over more miles of railroad

than any other nation. It has more miles of

commercial airways, more automobiles, and

more motor trucks than any other world

power. It has more miles of hard-surface

roads, of inland waterways, and of pipe lines

for petroleum products.

But we have also the knowledge that a

transportation system just as great for its

time bogged down pretty badly during the

World War, and it is up to the Commis-

sion’s representative of transportation to

see that that doesn’t happen again.

His job on the N. D. A. C. is divided into

two parts—the first the industrial mobiliza-

tion end and the other the plan for war

emergency.

On the first, the program should antici-

pate nation-wide and local transportation

needs as far in advance as possible, and

then should get the various carriers to

transport defense materials and men with-

out delaying the normal commercial busi-

ness of the country.

In war, of course, civilian needs would be

subordinated to military needs. But bar-

ring actual invasion, it is probable that

even war would not disrupt ordinary ship-

ments—provided plans had been made

wisely.

With wise planning as its goal, the Com-

mission has added to its staff representa-

tives of each type of transportation—men

who may fight each other to the last ditch

for business but who are working together

wholeheartedly in codrdinating transporta-

tion for patriotic purposes.

They've already guarded against one of

the worst tangles that marred transporta-

tion during the World War. Failure of

freight receivers to unload cars promptly

and the Governments wholesale and some-

times senseless use of priorities were the

chief causes of the bogging down of the

railroads in the war winter of 1917-18. Be-

cause of lack of codrdination between rail

and overseas transportation loaded cars

piled up in the terminals of eastern sea-

ports. The tangle was made worse by gov-

ernment. contractors ordering large quanti-

ties of materials which they wouldn't need

for weeks and which they had no place to

store when they received it. At one time

there were 5,000 carloads of piling for the

Hog Island shipyard clogging the Philadel-

phia yards, with the fanciful trimming of a

number of cars loaded with anchors for

ships whose keels hadn't been laid. Eventu-

ally there were over 200,000 loaded freight

cars—nine out of ten of them plastered

with red priority tags—serving as ware-

houses on wheels in railroad yards along the

eastern seaboard, and causing a shortage

of 150,000 cars in other sections of the

country and a traffic jam which extended

west of Pittsburgh. The snarl wasn't

cleared until all freight into the congested

area was embargoed while the misused cars

were being unloaded and the yards cleaned

out.

Now, because of that sad memory, the

Army and Navy Munitions Boards specify

that railroad cars must not be loaded with

defense materials unless it is known that

they can be unloaded promptly at their des-

tination.

The railroads are able to exercise the

same power to prevent tie-ups through the

operation of a well-tested embargo system.

Congestion in seaboard areas is averted by

their port control organization. It is notable

that last year the North Atlantic ports

handled more than three quarters as much

export business as they did in 1918, and

handled it without delay. It is notable, too,

that there hasn't been a car shortage since

1922.

Another step to help make certain that no

such shortage ever develops in any defense

emergency is a coordinated warehousing

program to eliminate the World War prac-

tice of using cars for storage. At key points,

ample space will be provided for storing

materials that cannot be absorbed by the

defense industries as soon as delivered.

The N. D. A. C. estimates that the na-

tional defense program, including additional

steel production, plant expansion, and camp

construction, plus the maintenance of a

large army and a possible increase in com-

mercial freight caused by better business,

will result in a maximum traffic increase of

less than 50,000 carloads a week.

That would be about eight percent of the

average weekly car loadings in 1939. In

that year, in one five-month period, car

loadings increased by 55 percent. Yet even

in the peak month of October, with an

average of 843,736 cars a week handled, the

railroads had an average daily surplus of

66,000 serviceable cars. That surplus would

be enough to take care of the defense in-

crease. But already 25,000 new cars have

been bought—and so that end of the job

will work out all right.

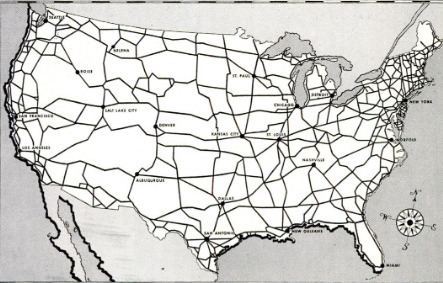

As important an asset as the railroads is

the nation’s network of a million miles of

hard-surface roads.

The War Department considers 75,000

miles of them to be of strategic importance.

But—14,000 of these are deficient in the

surface strength necessary to support heavy

loads; more than 4,000 miles should be

widened, and for military purposes most of

the strategic roads meed shoulders every

two miles at which truck convoys can park.

Bringing these roads up to the standard

desired by the Army will be an expensive

project, but it is a necessary one. Just as

necessary are the building of 3,000 miles of

access roads for camps, military posts, and

new industrial plants, and the construction

of city connections for strategically im-

portant highways.

Highways are already doing their full

share in carrying the industrial-mobiliza-

tion traffic, and as the defense load grows,

so will their importance increase. The

N. D. A. C. is aware that the value of the

roads would be heightened by uniformity

of regulations for trucks in the various

states. That's another problem that may

be solved.

Inland waterways play a part in the de-

fense program because

of the heavy cargoes of

ore, coal, grain, and oil

that can be sent to key

points in their barges.

We now have 17,000

miles of improved inland

waterways which are

more than four feet

deep, and the barge lines

which use them are in-

creasing in importance

as freight carriers. Most

of this traffic is on the

Mississippi, Missouri,

Ohio, and Illinois rivers

and on New York's Hud-

son Barge Canal, but

there also are barge

lines on the Sacramento,

Columbia, Snake and

other Pacific Coast riv-

ers, and on a few east-

ern and southern water-

ways. But in spite of

the growth of this busi-

ness the Great Lakes

whaleback steamers,

which transport heavy

cargoes of ore, coal,

grain and oil from May

to mid-December remain

by far our most impor-

tant inland water-borne

carriers.

Pipe lines move an

equivalent of 3,330,000

carloads of petroleum

and its products each

year. Since gasoline and

oil are the lifeblood of modern mechanized

warfare, this underground transportation

network would play a vital part in any con-

flict and, even in time of peace, contributes

greatly to our defense preparations by re-

leasing railroad, truck, and shipping ca-

pacity for other purposes.

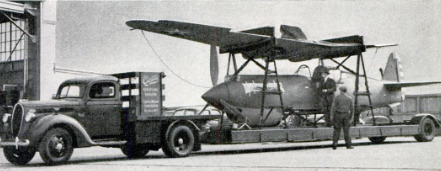

Another great asset is our highly de-

veloped system of air lines. In addition to

mail and passenger traffic, express service is

increasing so greatly that there is talk of

establishing an out-and-out cargo-carrying

line.

They're all part of the defense program—

just as much a part as are machine guns

and artillery.

And because that’s true, the millions of

workers on the transportation lines have

become civilian soldiers in the mobilization

of America’s resources.

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-02

-

pagine

-

82-85

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik