-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

How a rookie solider learns to handle a tank

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: How a rookie solider learns to handle a tank

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

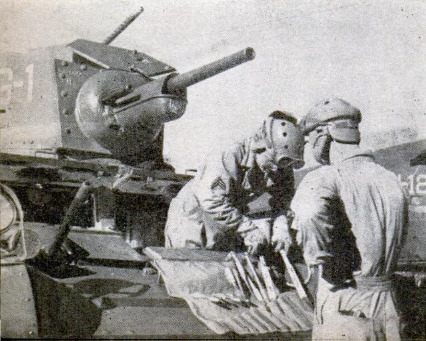

MASS-PRODUCTION education has

M been adopted by the Army to train

rookies for the recently organized Armored

Force. And it is working so well that

graduates are pouring from the Armored |

Force School at Fort Knox, Ky., into the

service at the rate of 400 to 500 a week.

Because tanks are the backbone of the

force, a large percentage of the graduates

are “tankers.” That means that they have

completed a rigorous three-months course

in which they were taught to drive and

care for a tank, read maps, use and main-

tain rifles, machine guns, and 37-mm. or

75-mm. guns, the latter depending

on whether they will be assigned to

light tanks which are fitted with the

37-mm., or medium tanks which

carry the 75's.

The Armored Force is proving

highly popular with recruits, but

soldiers with a yearning to become

“hell-buggy” drivers have a good

chance of getting what they want.

By next June the Army will have

four armored divisions, with 1,000

light and 400 medium tanks, plus

ten reserve tank battalions of 54

light or medium tanks each. Since

each member of a tank crew—four

men in a light tank, five in a

medium—must be able to fill al-

most any job in the tank, that leaves

plenty of room for trained tankers.

And the Army is already planning

another six armored divisions.

There are no special requirements

for tankers, though soldiers with

mechanical ability and a good record

in their general aptitude test are

preferred. But a recruit has to

satisfy his instructors in the course

that he will make a tanker, or he

is dropped.

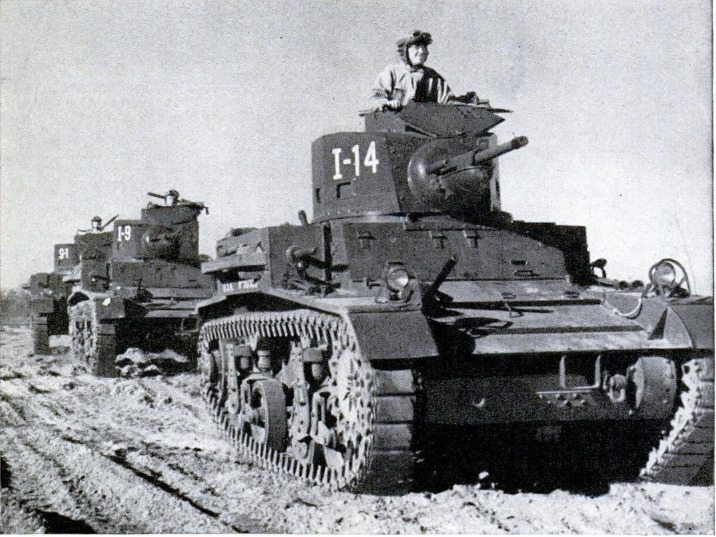

Before a recruit even approaches

a driving lesson, he has to learn the

general characteristics of the type

of tank to which he will be assigned.

If it is an M2Ad, the standard army

light tank, weighing 11 1/2 tons, he

learns that it will make better than

50 miles per hour on a highway,

and up to 30 cross-country, and that

our army officers consider it the best

little juggernaut of its kind in the

world, superior to anything used by

European armies.

If he is going to a medium-tank

regiment, he gets an earful about

the M2, a 20-ton job officially

capable of 32 miles per hour on

highways and up to 20 cross-country.

Then things come thick and fast.

One day the budding tanker takes

driving lessons. The next day he

will work in classrooms, studying

tracks, engines, transmissions, and

other complicated parts.

The first steps in the driving are

learned with the tank standing still,

as even a light tank costs more than

$20,000, and the Army doesn't want

to spoil any.

The student is plopped into the

driver's seat on the left side of the

tank. Under each hand he finds a

“joy-stick,” each with an electric

trigger connected to fixed machine

guns in the sides which are aimed by aiming

the whole machine. The only familiar

items will be the clutch and accelerator,

which are like those in an automobile.

“Pull back on the right stick, and the

tank will turn to the right,” he is told. The

left one will turn the tank to that side.

Because the control sticks are attached

to two brake bands in the transmission,

each of which controls one track, pulling

back on both at once will stop the tank.

It sounds easy until the student finds that

to operate the gearshift lever, mounted on

a huge six-speed transmission, he has to

let go of one control stick. The trans-

mission, incidentally, snuggles right along-

side his right leg, and gets unpleasantly hot

when the tank is under way.

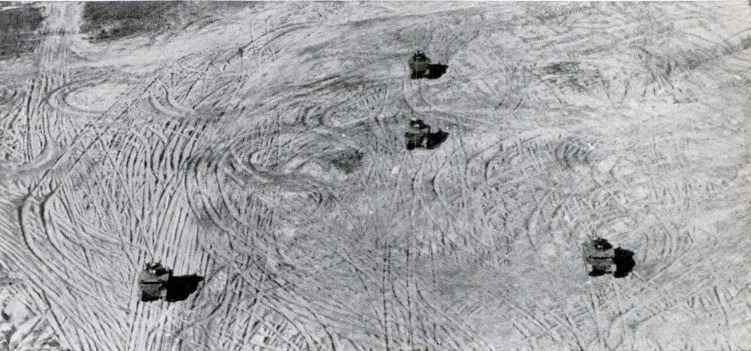

Once he has mastered the theory with the

tank at rest, he learns to operate the vehicle

on smooth ground, first in low gear, later in

higher gears and at higher speeds. The

final phase is cross-country work, which

means anything from bouncing over stone

walls at 20 miles per hour to burrowing

through ditches and shoving over three-

inch trees. He must learn, for instance that

if he doesn’t “give her the gun,” when his

tank noses down a steep pitch, it may roll

right over on its back.

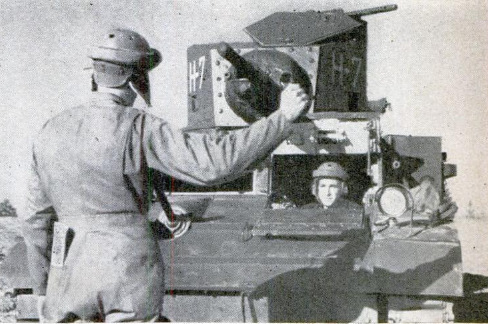

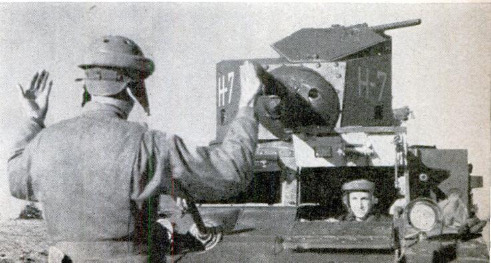

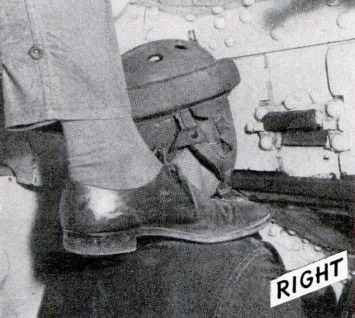

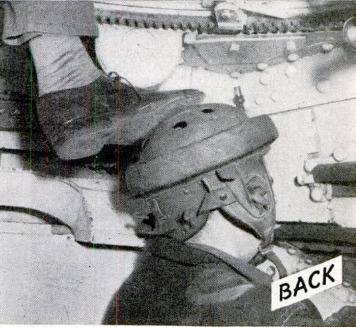

All this has been done with the armor

plate open in front of the driver, enabling

him to see where he is going. Now he must

learn to drive the tank when it is “buttoned

up,” with all the armor in place and his only

means of looking out a narrow slit. He

begins to develop sensitive shoulders, be-

cause the tank commander, who has slits

on all sides of him and can therefore see

all around even when the turret top is

closed, directs the driver with the toe of

his boot. This is necessary because the in-

side of a tank under way is noisier than

the proverbial boiler factory, and even

shouted commands are inaudible.

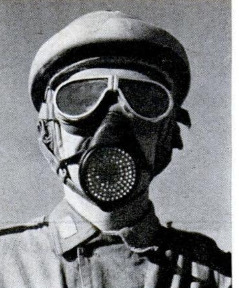

In tanks equipped with radios, such as

platoon and company commanders’, the

assistant drivers must be radio operators

as well as gunners and drivers. Recruits

with an ear for code are trained for this

duty after learning the other aspects of

tanking. It is not an enviable position, be-

cause in action the operator must be able

to tune his set and hear what is coming in,

and send as well, with hot shell casings

from the 37-mm. gun in the turret and the

machine gun beside his

seat pouring down upon

his head, possibly down

his neck, if he forgot to

“ button his collar.

To protect the tankers

from bruises when the

tank is bumping across-

country, special crash

helmets are provided,

though even with them

tankers have been knocked

unconscious when the

vehicle took a particular

vicious bump at high

speed. Khaki overalls are

standard uniforms, and

they rarely stay clean

long. After each day's

run, a tank crew must

inspect their machine, re-

port any necessary repairs to the company

commander, fuel and lubricate the buggy

for the next day, and, if at a home station,

clean the tank as well.

In the meantime, the tanker has been

learning how to care for and make minor

repairs to his tank and its power plant.

He has studied the general theory of the

four-cycle, internal-combustion engine;

then he specialized in the

type of engine which he

will find in the regiment

to which he will go after

graduation. In the M2A4

this is either a seven-cyl-

inder, radial, air-cooled

250 - horsepower gasoline

engine, or a Diesel of sim-

ilar type and power. In

the M2 it is a more pow-

erful radial gas engine.

The end of the school

course doesn’t mean the

end of his training for a

tanker, however. After he

is assigned to a regiment,

there are cross-country

marches, gunnery prac-

tice, and night maneuvers

to keep his mind on his job.

For the more ambitious recruits who want

quick promotion, there are study courses

and examinations. And although a tanker

probably won't find a job driving a tank

when he returns to civilian life, it's a safe

bet that he will be far wiser about the

workings of gears and internal combustion

engines. He may even find that he is a bet-

ter automobile driver.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

David M. Stearns (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-03

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

56-60

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 3 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 3 1941