-

Titolo

-

Destroyer heating power

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Destroyer heating power

-

extracted text

-

DESTROYERS of a new American type,

classed as high-speed troop transports,

have joined the fleet. In conjunction with

landing maneuvers practiced by TU. S.

Marines in Caribbean waters, this winter,

they are believed to have solved the prob-

lem of quelling a fifth-column uprising in

Latin America.’

In response to an appeal for aid, the ves-

sels will race to a trouble spot, carrying

picked, heavily armed Marine detachments.

If hostile guns bar entrance to a harbor,

the men will be prepared to ferry them-

selves ashore on any convenient beach, with

armed landing boats of special design.

Their duty will be to suppress the trouble

makers, or hold them at bay until slower

transport vessels arrive with reinforcements.

‘War events abroad have proved the ad-

vantage of getting to places first, even if

it is with only a small body of crack troops.

Reconditioned destroyers in Atlantic

service have been transformed into the first

of the high-speed transports, by removing

the deck-mounted torpedo tubes—super-

fluous except in naval battles—and rear-

ranging eating and sleeping quarters to ac-

commodate the extra men aboard. By ex-

perimenting with these converted ships, the

Navy is standardizing their design, saving

time and avoiding possibly costly errors in

building an untried type.

Likewise, old but serviceable destroyers

have been chosen to test other naval inno-

vations. Several are being converted into

our first antiaircraft ships. Like a number

of cruisers of the British fleet, which intro-

duced the type, they will become floating

nests of high-angle artillery, and will have

the sole mission of shooting down air raid-

ers. They are expected to mount three-inch

guns for bringing down high flyers, and

1.1-inch rapid-fire guns of a recent design to

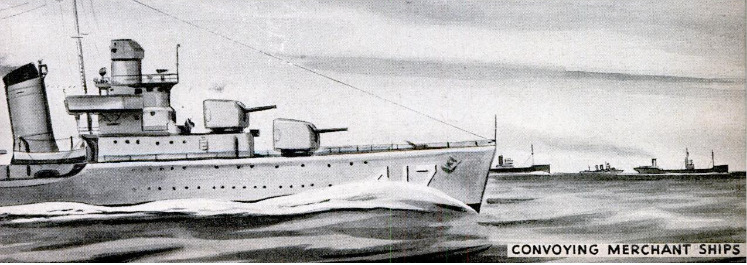

deal with dive bombers. Besides serving with

the battle fleet, such vessels would guard

convoys of merchantmen against the new

menace of air bombing.

More than a dozen converted destroyers

will serve as mobile bases for the Navy's

giant patrol-bombing planes. Soon after

this country acquired the right to establish

a naval base on the British-owned island of

Bermuda, for example, the United States

destroyer George E. Badger dropped anchor

near Hamilton and began operating as a

tender for the American flying boats. The

incident illustrates how the whole chain of

Atlantic outposts gained in our destroyers-

for-bases deal with Britain can be used to

our immediate advantage, pending com-

pletion of more permanent facilities.

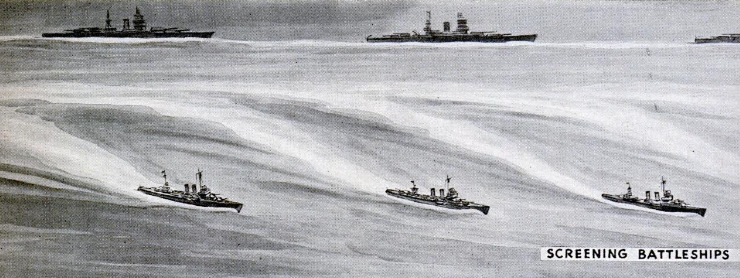

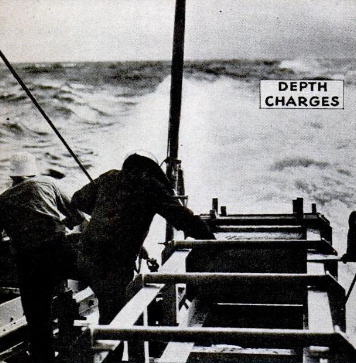

These new duties supplement the varied

ones that make a destroyer the most ver-

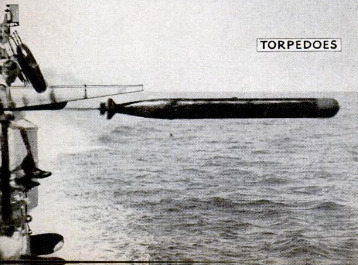

satile of major fighting craft. In a naval

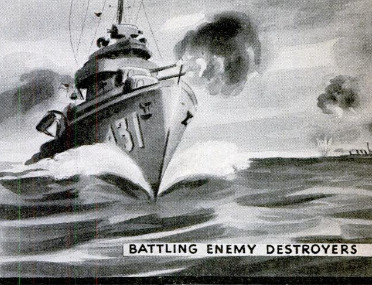

battle, destroyers conduct torpedo attacks!

upon enemy battleships; they “screen” their

own against submarines, with depth charges,

and against enemy destroyers, with shells.

Their double-purpose guns can be elevated:

to extreme angles for use against aircraft.

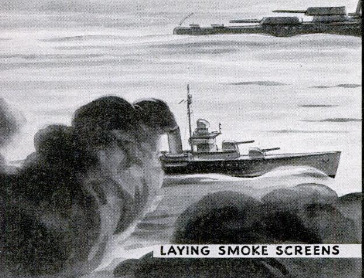

To hide offensive or defensive maneuvers,

their funnels belch smoke screens. At night,

their star shells illuminate enemy targets.

In addition, destroyers serve as fast mine-

layers and minesweepers; escorts for con-

voys of cargo ships; submarine chasers on

the high seas; and, within the limits of their;

cruising radius, commerce raiders. Destroy-

er crews of our own Neutrality Patrol,’

while under orders only to “observe and

report” whatever goes on in American

waters, have been obtaining first-class

training for reconnaissance in war. Among

other things, they have followed. and ascer-

tained the nationality of ships which would

not signal their identity.

Only lightly armored, a destroyer can be

sunk, according to the U. S. Coast Artillery,

with an average of half a dozen six-inch

shells that pierce its sides. The British de-

stroyer Gurkha, attacked early in the cur-

rent war by German aircraft, was the first

modern warship of its size to be sent to the

bottom by air bombing.

Nevertheless, experts rate destroyers as

second only to battleships in deciding the

outcome of a sea engagement. Ton for ton,

they are the most powerfully armed of any

type of man-o’-war. To a modern fleet, they

are indispensable.

By recently announcing the addition of

. 40 more destroyers to its already gigantic

building program, the U. S. Navy empha-

sizes the value of these swift, hard-hitting

craft. And a $1,750,000 seagoing dry dock,

to follow the fleet wherever it steams, is

its answer to the question of what to do

with destroyers seriously damaged in ac-

tion, or in need of complete overhaul, far

from established navy yards. The mobile

base will service them at any lonely outpost

—perhaps in the South Seas, in Alaska, or

at one of the “stepping-stone” islands be-

tween Hawaii and the Orient.

A smaller floating dock of 393-foot

length, the ARD-1 was launched and com-

missioned in 1934 to try out the idea. It

has been stationed at San Diego, Calif.

According to Rear Admiral Ben Moreell,

head of the Navy's Bureau of Yards and

Docks, “That was the first floating dry dock

of this type that we ever built. One of those

1,500-ton destroyers is the largest it will

take, and even with those you can’t pull a

shaft in it. It will not take a destroyer

leader or a large-sized submarine. It was an

experimental structure, and it has been so

successful and the fleet is so pleased with

it that we want to go ahead and build

this larger dry dock. It will take the largest

new-type submarine or destroyer leader,

and you can pull a shaft on that destroyer

leader.” Impressed by the Admirals words,

Congress voted funds for the novel dry

dock last June.

According to latest figures, this country

leads the world in the number of destroyers

built and building, with a total of 365. Next

in order come the British Empire, 240; Ja-

pan, 146; Italy, 132; Russia, 83; France, 80;

Germany, 47. Because of wartime secrecy,

some of these totals necessarily are esti-

mates, based on the best unofficial infor-

mation.

As for destroyers completed at this writ-

ing, the British Empire trades places with

us at the head of the list, and the other

powers follow us in the same order. With

135 destroyers afloat, Japan comes uncom-

fortably close to our 155 ships of the type,

especially in view of the comparatively large

proportion of over-age, reconditioned Amer-

ican destroyers. Perhaps because of this

situation, the U. §. Navy has just given its

construction program a shake-up. Con-

tracts for a number of destroyers and cruis-

ers have been redistributed so that each

shipbuilder, to the greatest possible extent,

will concentrate on turning out a single type

of standardized design. Experience gained in

constructing one vessel will thus help to

speed up work on the next. As a result, naval

men expect to swell the total of warships

that we are currently producing at the rate

of one every twelve days.

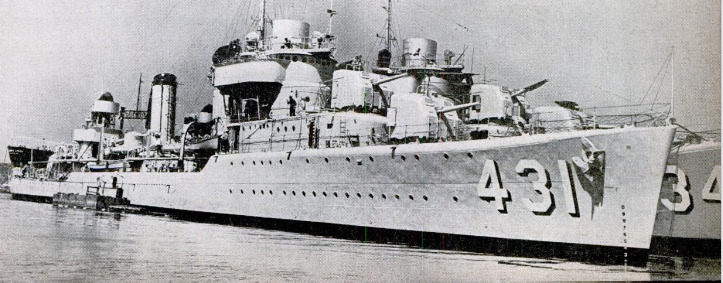

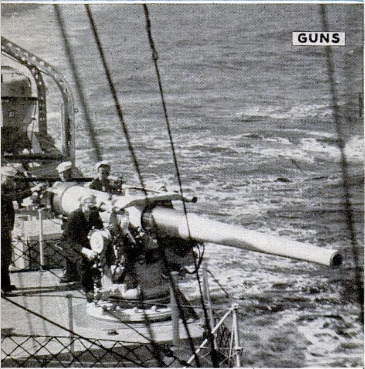

Today a typical American destroyer of

1,500 to 1,700 tons carries up to six five-inch

guns, and from eight to sixteen torpedo

tubes. “Heavy destroyers,” a 1,850-ton type

of destroyer leaders, mount two more guns.

The two classes are expected to merge into

one, in destroyers still to be laid down.

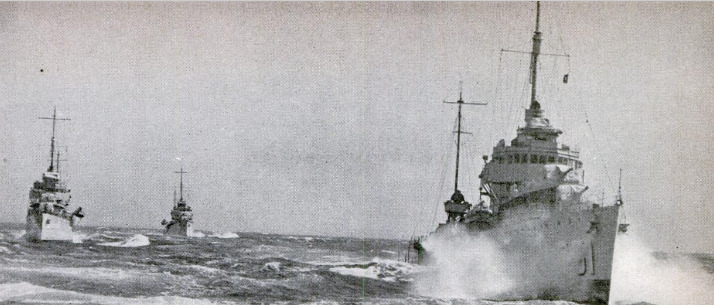

No place for a comfort-loving landlubber,

a destroyer bucking a heavy sea may roll as

far as 45 degrees from the vertical, and

crews dine on sandwiches when the cook’s

pots begin sliding about. The slim hull

virtually is built around the throbbing power

plant of 50,000 horsepower, Which propels

the latest type of American craft at 40

knots or more than 45 land miles an hour.

From full speed astern, at half this pace, the

ship can leap to full speed ahead in exactly

one minute and five seconds.

Its boilers, pride of the Navy's engineers,

feed steam to the turbines at the extreme

pressure and temperature of 600 pounds to

the square inch, and 850 degrees. Darken

the interior, and the pipes carrying the su-

perheated steam will be seen glowing red.

Success of the innovation on the destroyer

Somers, late in 1937, has led to its adoption

for all new battleships, cruisers, and destroy-

ers. But its use in destroyers has by far the

greatest significance. Tests show a fuel

saving for these craft of 14 percent—which

means that with the same amount of oil,

they can cruise proportionately farther.

To grasp what that means, consider that

the whole fleet's radius of action depends

upon the cruising range of its destroyers.

These essential craft are the ones that tie

the Navy to its bases, for battleships and

cruisers can travel many times farther be-

fore refueling. With the new boiler instal-

lations, destroyers can steam 2,500 miles or

more from a base and return, extending the

mighty power of our fleet farther than ever

before

-

Autore secondario

-

John E. Lodge (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-03

-

pagine

-

73-76

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik