-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

What has America learned from the war

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: What has America learned from the war

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

BOUT the busiest students in the United

A States now are the officers of the

‘Army and Navy. The battleground of |

Europe is their university. Like other tech-

nicians, they have to keep learning as they |

go, and they learn best by experience.

Now, if you are running a subway, you |

are running it all the time, but if you are |

in the military profession you have to wait |

for a war. After all the studying of past

wars, after all the planning and preparing, |

you still have to learn by fighting—either

your own or somebody else's. Somebody

else’s is less expensive.

The general lessons of the present and |

recent European campaigns are not new, |

but they bring out new phases of principles

which were known to all educated soldiers.

One is the vital necessity of close cobrdina- |

tion of all branches, under unified command. |

If there was any miracle about the victories

in Norway and Flanders, is was in the skill |

with which the Germans welded their |

specialized arms into a single fighting

machine. It was a remarkable demonstra-

tion of teamwork in combat against op-

ponents who were not prepared and drilled

in anything like the same degree. The

results were conclusive.

It was not solely a triumph of machines.

Mechanization is extremely important, but |

everything depends on the manner in which

the forces are used. The rout of the

mechanized Italian forces at Guadalajara in |

the Spanish war by relatively unmechanized

troops (an episode repeated with variations

early in the Greek campaign) shows that

machines as such do not win a war. Ma-

chines magnify both striking power and

vulnerability. On the wrong terrain or in

bad weather, or under bad leadership, a

mechanized army can be led into disaster

faster than one equipped only with the

traditional arms.

The “secret” of the effective use of

mechanized ground forces lies in finding a

weak spot and hitting it for all it is worth.

The principle is older than mechanization;

Sheridan used it in the Civil War with

cavalry. He massed his cavalry in one place

and broke through, and he had the knack of

picking the right place. Before his time

the tendency was to distribute cavalry along

a wide front, just as the British and French

mistakenly used their tanks and other

mechanized units in the present war.

For all their stress on mechanization, the

Germans had nine or ten infantry divisions

for every “panzer” division. When they

achieved a break-through they had the

necessary infantry power to keep and ex-

tend the opening. The mechanized forces,

once they got through, were able to work

havoc behind the enemy lines, for they

were virtually self-sufficient, forced neither

to return to their bases for supplies nor to

rely on communication lines. The necessity

for self-sufficiency of fast-moving mecha-

nized forces is one of the important practical

lessons from what happened in France.

Aside from such general conclusions as

these, there are indications that the func-

tions of some of the arms will be different

in the future. One factor about which

American soldiers are speculating is the

use of the engineers as a combat arm.

Of course, engineers have always been

prepared to fight, although their primary

function is to make routes passable for

their own forces and impassable for the

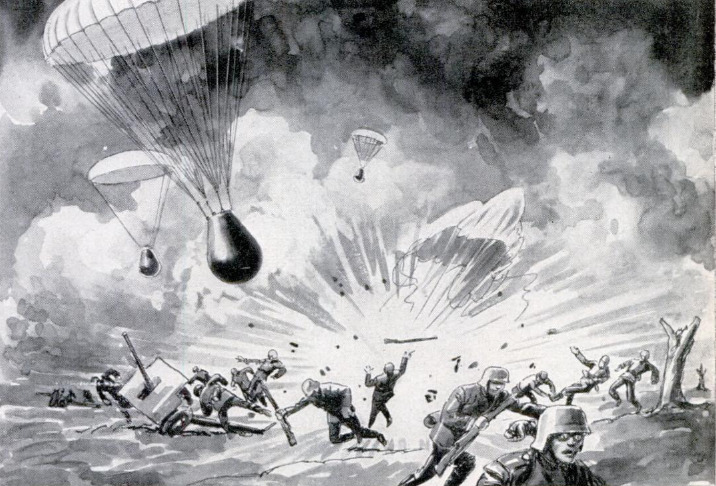

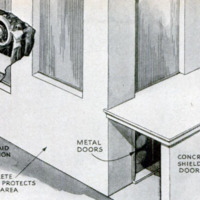

enemy. The Germans, however, used en-

gineers deliberately for some of their

toughest fighting — substantially as shock

troops. The invasion of Belgium was led

by a battalion of engineers, and fortifica-

tions such as the Belgian Eben Emael,

which were virtually invulnerable to artil-

lery fire, were reduced by engineer combat

units with explosives. Besides explosives in

great quantities, these engineers carried

rifles, machine guns, hand grenades, flame

throwers, scaling ladders, crowbars, long

poles, smoke candles, and about every other

portable assault weapon that can be im-

agined. They closed in by taking advantage

of shell craters which the artillery made

for them. The occupants of the fort were

unable to reply effectively because the

German artillery kept up a continuous fire

on the ports and turrets. Finally the en-

gineers were able to get right up against the

walls of tae fortress and to blow up turrets

and doors with planted explosives.

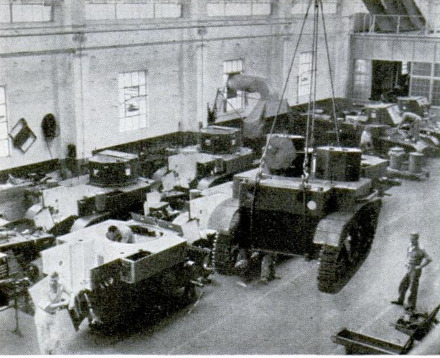

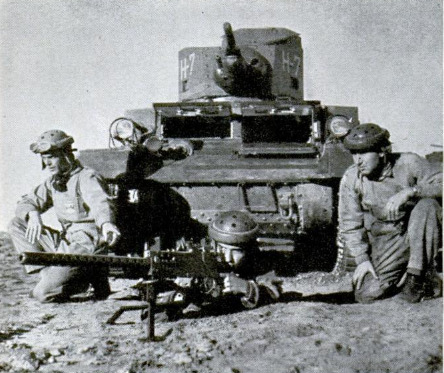

Next to the airplane, the tank is the

chief new weapon both of the first World

War and the present one. And as far as

this war is concerned, the heavy tank is

the one to watch, not the light tank. One

military observer remarks that

the effectiveness of the heavy

tank as a break-through

weapon was something of a

surprise to soldiers as well as

to civilians. Except for Ger-

many, he says, after the last

war the nations deluded them-

selves into the belief that

swarms of tankettes would be

effective for open warfare, and

this while they were building

fortifications such as the Ma-

ginot Line, the Mannerheim

Line, and the Crech Sudeten-

land forts, against which light

tanks had about as much

chance as a tack hammer

against a bank vault.

This commentator believes

that the Russians could have

breached the Mannerhelm Line

at considerably lower cost with

large tanks than with the

artillery, planes, and masses

of men they eventually used.

They started with thin-skinned

‘medium-weight tanks, which

proved ineffective. In con.

trast, the Germans on the

Western Front relied on

heavily armored tanks from

the outset. According to one

report, these tanks weighed 70

tons aplece and were armed

with 77-mm. or 156-mm. can-

non, and flame throwers. The

Germans have not provided

samples, and one can only

speculate as to the actual

weight and armament of these

machines. The only thing

cortain is that they were

heavy and numerous enough to

{achieve the objective, and that

they were fast for their size. Weight alone

was not a determining factor. It is known

that the French threw into the action some

twenty 70-ton tanks of an obsolete design,

and these were hopelessly ineffective against

the faster German machines.

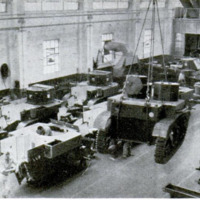

The monster tank has two missions (mili-

tary men are fond of that word)—to break

through, and to repel enemy tanks. It has

to be as agile as its size will permit, climb

well, and span broad ditches. It must be

heavily armored, since antitank artillery is

constantly increasing in effectiveness, and

calibers as high as 75 mm. may be used

against it. Its own armament depends on

its purpose. Against ordinary fortifications

it may carry two or more 75 mm. or 165-

mm. cannon. For close-in protection and

against infantry, it uses machine guns. In

addition to this arsenal, it has need for an

antiaircraft gun as well,

Naturally, it is not an extremely fast

machine. Small tanks are fast, and if out-

gunned they can always make a run for it.

The heavy tank must shoot its way out.

But that is a slight disadvantage. The chief

trouble with these heavy tanks is in trans-

porting them before they go into battle.

Since few highway bridges can sustain their

weight, they must travel by rail. That lim-

its their width in most countries to 10 feet

4 inches, and height to 14 feet 5 inches

above the rails. They can be carried on flat

cars if their weight is not over 80 tons, but

a better method is to equip them with rail

trucks which are a part of the tank itself,

s0 that several can be drawn in tandem by

one locomotive, or they can move on rails

under their own power.

An example of the adaptation of old

weapons to new conditions under stress of

necessity is the use of the 75-mm. gun

against tanks by the French. Since a tank

is fairly fast, it is necessary to swivel the

plece rapidly to keep up with the target.

All that this involves is the addition of a

circular metal platform with six-inch metal

prongs on the under side. This is carried

separately on a caisson. To operate against

tanks, the crew throws the platform on the

ground and jumps on it to imbed the prongs.

On its upper surface the platform has a

flange which forms a circular track for the

wheels of the gun. The trail is shifted by

one or two members of the crew. Used in

this way, the 75-mm. gun did fairly effective

work as a substitute for the standard

47-mm. A. T. gun, with which the French

were none too well equipped. It was no

more than an improvisation, but one of

some interest to the military student.

The United States has no big tanks on

hand, but it is understood that a heavily

armored model of 50 or 60 tons is about

ready for field testing. The fact that we do

not have hundreds or thousands of such

Juggernauts ready to go into action is no

cause for alarm. The likelihood of our need-

ing them for use at home is extremely re-

mote. If they should ever be called on, the

Army will have them and know how to use

them. It has kept abreast of military de-

velopments all over the world and has never

subscribed to the now discredited theory

that tanks and other mechanized units

should be “encadred” within larger units.

Our tacticians favored the independent,

synchronized-action method before it was

proved in the field by the Germans, and it

is being taken into full account.

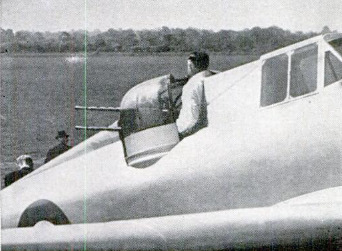

The performance of American aircraft in

England recently has been severely crit

icized. These criticisms, in so far as they

relate to models supplied during 1940, are

in large part justified. The planes that have

gone over have been fast, highly maneuver-

able, and well built, but most of them

have been underarmored and undergunned,

sometimes complex in operation, and not

equipped with important accessories of

modern aerial warfare such as self-sealing

fuel and ofl tanks.

I. should be realized, however, that every

new model of anything, whether it is a

radio receiver or a milk can or an airplane,

is found to have things the

matter with it when it gets

into the field. That is bound to

be doubly true of such a com-

plex, nervous, and changeable

business as air fighting. Many

basic questions of aircraft de-

sign are not yet settled. Take

the matter of the air-cooled

radial engine and the liquid-

cooled engine. The British pre-

fer the latter for pursuit

planes, but there are plenty of

arguments on the other side.

The air-cooled motor is being

produced in quantities; it is

the type used by the commer-

cial airlines. It warms up

faster—any motorist can ap-

preciate what that means in

dependability—and by the

same token it has a longer

life. It is lighter. The fire

hazard is slighter. There is

no danger of loss of cooling

fluid through gunfire. All

these considerations may now

have to go by the board as far

as pursuit planes are con-

cerned, but the probability is

that both air-cooled and liquid-

cooled motors will continue to

be used to power military air-

planes.

One other point should be

noted. The planes on which

the United States relies fcr

immediate protection, especial-

ly the naval types, are highly

satisfactory for the purpose

for which they were designed.

The air defense of the United

States relies primarily on the

bomber. The pursuit ship plays

a secondary part. Pursuit and

interception are of far more

importance to the British than

to us. One experienced Ameri-

can Army officer sums up the

situation as follows: “It must

be remembered that the defense of the

British Isles is actually a ‘special opera-

tion.” American planes were not designed

for this. Our large-view problem of military

aircraft is quite different from the pressing

situation in which the British now find

themselves, and it would be a grave mistake

to base design entirely on the momentary

needs in the defense of the British Isles.”

None of this alters the fact that with the

information now coming over from England

the United States will make as much prog-

ress in combat-plane design in a year as

in two or three years of normal develop-

ment. The same is true of the operation

of fighting planes. The power-driven gun-

turret is a case in point. A turret in an

airplane is a kind of universal joint which

permits aiming guns in almost any direc-

tion. The United States had several types

under development before the question of

aid to Britain came up. But the British tur-

ret which became available to American

designers in October, 1940, is very good,

the result of several years of experimenta-

tion, and no doubt it will influence the de-

sign of American turrets. It is hydrauli-

cally operated. There are also pneumati-

cally, electrically, and manually operated

turrets. One thing that should be guarded

against is the installation of more than one

type in a given plane. Maintenance diffi-

culties are quite enough without mixing up

several types of mechanism for the same

Job.

One advantage, from a military stand-

point, of the present tie-up between British

and American aircraft technicians is that

our people get accurate information on Ger-

man types. German planes brought down in

England can sometimes be repaired and

flown almost with their original perform-

ance characteristics. What is perhaps even

more important, the results of large-scale

air fighting can be obtained for the develop-

ment of American aircraft. Finally, some

idea can be had of what the Germans are

going to spring in their new models.

One of the best of their current types is

the Messerschmitt 110. Its design and per-

formance are now accurately known, since

the British have several of them. It is an

all-metal piane powered by two 1,150 h.p.

motors, liquid-cooled. The speed is 365

m.p.h. at 19,000 feet. It mounts five machine

guns and two 20-mm. cannon. None of these

fires through the airscrew disk, so that

there is mo limitation of the rate of fire

on that account. All the forward armament

is concentrated in the nose—four of the

machine guns and both of the cannon. The

fifth machine gun covers a 120-degree arc

rearwards. There is a long-range version

of this model which dispenses with the can-

non; this is the one which has been ex-

tensively used for bombing as well as for

escort and pursuit. It can carry two 550-

pound bombs in the center section.

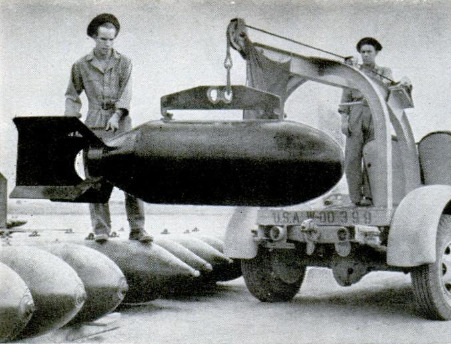

The results of air fighting to date indicate

that the smallest gun which can damage a

plane seriously is the .50 caliber size. Rifle-

caliber bullets are effective only against

personnel, and as armor protection im-

proves it becomes more and more neces-

sary to damage the plane rather than its

occupants. There

have been innumerable cases of planes re-

turning in flyable condition full of .30-

caliber holes. One explosive bullet or small

shell is more effective than a barrage of

nonexplosive projectiles.

Some British commentators think ill of

four-engine bombers. They assert that the

four-engine type was based on peacetime

theories and that a year of war has drasti-

cally modified the requirements—which

would of course apply to their Sunderlands

as much as to our Boeing B-17s. This school

of thought prefers smaller, faster bombers

which can be used in daylight. However,

the reports on the B-24 (Consolidated

Model 32) are rather favorable. This car-

ries four 1,200 hp. Pratt and Whitney

Wasps and has a top speed of 300 m.p.h.

It has British turrets in nose and tail.

An item of interest to those who would

like to see more experimentation with trans-

ports converted into bombers is the excep-

tionally favorable report on the Lockheed

Hudson, which is a converted airliner. The

undercarriage is said to be weak, but this

model has fought off and shot down Hein-

kel HE-115 seaplanes and Messerschmitt

110s. It has been used more for reconnais-

sance than for bombing, but so far it seems

to be one of the most useful types we

have sent over.

‘The British predict that eventually all

fighters will be equipped with turrets. They

favor two-seater fighters, especially for

night worl; it is becoming increasingly dif-

ficult for one man to do both the fighting

and the piloting. They expect that future

day bombers will have fighter performance

and little or no armament. “If there is

fighting to be done, its escort will have to

do it,” one writer predicts. “The part of the

bomber will be simply to bomb and run.”

There are many serious problems of mass

production of military implements which

have not been solved. In design, also, mis-

takes have been made, and there is no

guaranty that they will not be made in

the future. All that can be said for the

technicians is that they learn from their

mistakes rather quickly and don’t keep on

making the same ones over and over, as is

the rule in some. other lines of human en-

deavor. No nation has a monopoly on tech-

nical skill; they are all exporters and im-

porters. But we may be sure that our

technicians, adding what they are getting

from abroad to their own endowments, will

give a good account of themselves.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dreher (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

55-59, 220

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941