-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

School for sky soldiers

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: School for sky soldiers

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

Tz parachute troops of the Army and

Marine Corps are tough outfits. Only

outstanding men with at least a year's ex-

perience in uniform are picked and they are

toughened scientifically, They are hard-

boiled “canopy” jugglers by the time they

are assigned to a parachute battalion.

Ground and lofty tumbling is their meat

from the moment they are accepted for the

service, for which the number of volunteers

far exceeds the rate of acceptance. They

must be muscular and intelligent and gifted

with initiative, and nobody weighing more

than 185 pounds is accepted. By the time

they are ready for service any one of them

probably could throw over his shoulder the

Siamese tumbler who made the first record-

ed parachute jump from a pagoda in 1687.

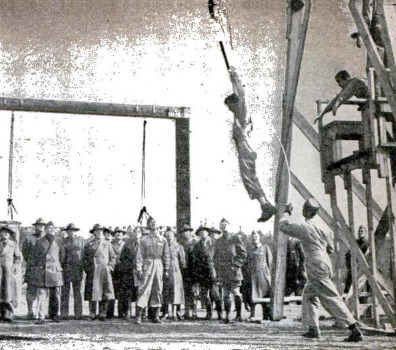

Starting with drops of six or eight feet

to get used to the jolt of landing, they

progress by way of the tower-guided para-

chute to jumps from planes, and all the time

they are being hardened for wrestling

matches with recalcitrant, gust-driven

‘chutes and for the exacting field service for

which a ‘chute jump is merely the prelimi-

nary. They must be capable of a good many

miles a day afoot, running a good portion of

it. A ’chute soldier seldom is seen walking

while on duty; he executes all orders at

double time.

The parachute troops have gone back to

the old static-line ’chute, which has a strong

cord attached to the plane, because of the

special conditions of their work. A static-

line 'chute permits drops as low as 100 feet

above the ground, and in war that means

less time for enemy “parashots,” or sporting

old gentlemen with shotguns, to pot the

parachutist.

Our Army and Marines are not planning

to put the troopers through any 100-foot

jumps in training or maneuvers, but it is to

prepare for low jumps, as well as leaps in

choppy air and high winds, that they are

taught tumbling. All their exercise is di-

rected toward strengthening their shoulders,

arms, and leg muscles, and to make it

second nature for them to land relaxed, on

their toes, sink onto their knees, and twist

quickly so that they will hit on the soft part

of the body.

In normal air a parachute drops at about

the same rate of speed as a skyscraper ele-

vator, though unlike the elevator it does not

slow up before stopping. If the air is choppy

it may fall nearly twice as fast as normally.

Normal is 16 to 18 feet a second, with the

life-saving ‘chute, which has a spread of

24 feet. The parachute Lroops, however,

use 28-foot chutes, which let a 180-pound

man down at the rate of 12 feet a second.

This permits a man to carry more equip-

ment than does a flyer bailing out of a

disabled plane.

Under war conditions, when there may be

no choice of weather or terrain, they'll need

slow parachutes. Even in a moderate wind,

a parachutist often lands going faster side-

ways than he is falling, which is pretty

tough if he tumbles on rocks or concrete.

A story current among U. S. Army para-

chutists is that the Germans lost 47 percent

of their air troops at Narvik, by dropping

them too low and on sharp rocks.

The German parachute trooper cannot

maneuver his ’chute, for all the suspension

lines come in at one point and he hangs

below that like a monkey on a string, unable

to reach them. The 24 lines on the American

life-saving 'chute and the 28 on the trooper’s

larger ‘chute are gathered at four points of

suspension on the harness, two on each

shoulder. By grabbing the six or seven lineswhich come in at one point, and pulling

them down a yard or so, the ’chutist can

slip or “fall off” in that direction, and thus

avoid falling into a tree or water hazard.

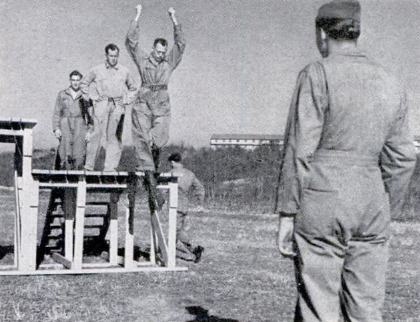

Men accepted for training as parachute

troopers must have “demonstrated soldierly

qualities, agility, athletic ability, intel-

ligence, initiative, determination, and dar-

ing,” and be able to learn map reading,

sketching, radio, and demolition. They must

be expert with their weapons, unmarried,

and not more than 32 years of age. They

are turned down if heart action or blood

pressure is even slightly off normal, or if

they are subject to airsickness. The men

receive additional pay, which is 50 percent

more than what their regular ratings draw.

On arriving at the training station, Pete,

as we will call our typical parachutist, is

issued, in addition to his regular uniform, a

suit of khaki coveralls, with a belted back

and pleated shoulders, to afford maximum

freedom of movement. At the wrists and

ankles are adjustable bands, with buttons

so they can be fastened snugly. His 14-inch,

laced leather boots have an ankle brace built

in, to be tightened before he jumps. Every-

thing a parachutist carries in his pockets

must be well fastened in: a jump amounts

to about the same thing as being picked up

by the heels and shaken, none too gently.

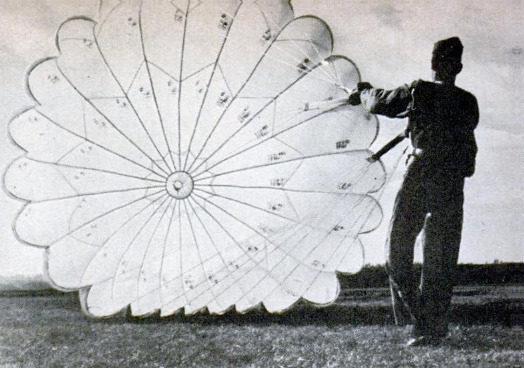

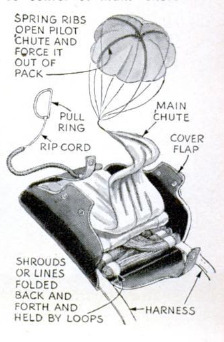

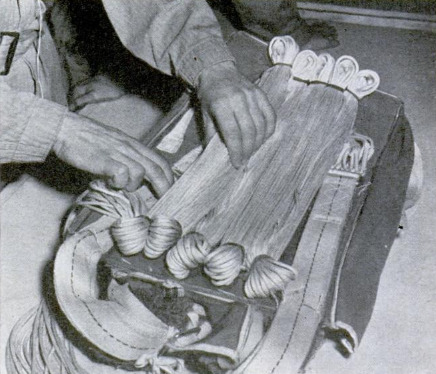

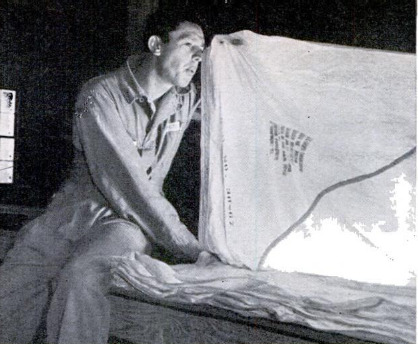

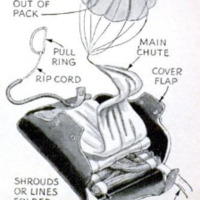

Pete's first lesson is in nomenclature. He

learns that the big silk umbrella itself is

called the canopy, and that although it

weighs only 1.35 ounces to the square yard,

it has a tensile strength of 40 pounds to the

inch, and a minimum tear strength of 41%

pounds. A 24-foot canopy is made up of

96 pieces of silk twill, sewn with four

needles. A 28-foot 'chute contains 112 pieces.

Four pieces, or panels, are sewn to form a

gore, a narrow, pie-cut piece which is a yard

wide at the edge of the canopy, and tapers

down to less than two inches at the center.

There is an 18-inch hole in the center of

the canopy, called the vent, with a rubber

garter sewn inside its edge so that as the

‘chute starts to open the hole is only four

inches across. Air pressure usually expands

the vent to its full 18-inch diameter, and

air escaping through this hole, of course,

allows the ’chute to fall. But in strong up-

drafts, a parachutist may actually go up-

ward, until he spills wind.

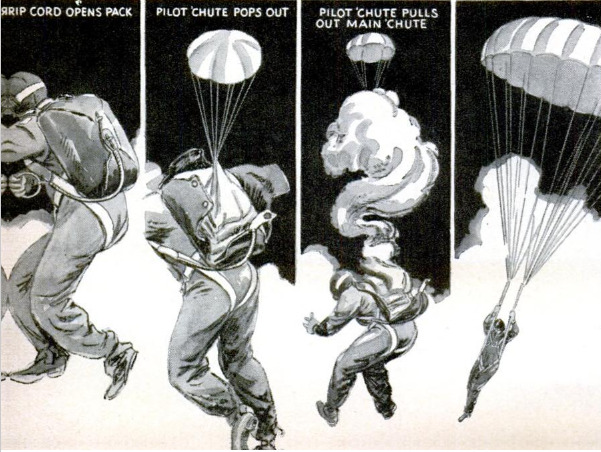

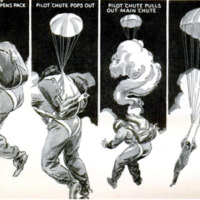

Above the vent is a 36-inch pilot ’chute.

A steel spring makes it open first, at least

in theory, and it helps pull the big ’chute

open.

Leading from the vent, down through tape

between the gores, then out in the clear for

16 feet more, to four points on the shoulder

harness, are the suspension lines. These are

of silk, too.

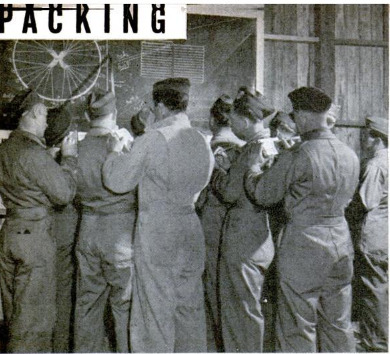

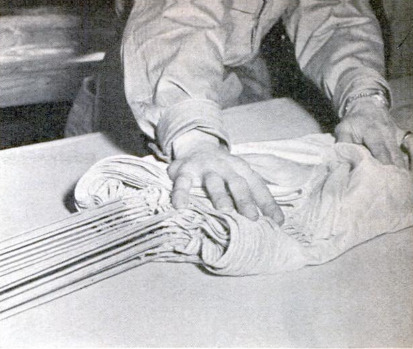

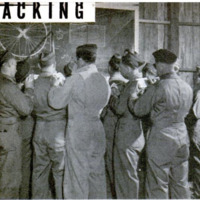

After the lesson in nomenclature, Pete

takes the first of a number of lessons in

inspecting and packing a ’chute. Every

parachute trooper must inspect, air out, and

pack his own ‘chute every 30 days.

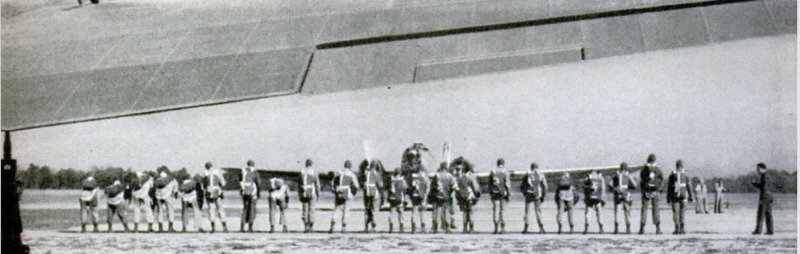

Most of the 412 men of the Army's first

unit, the 501st Parachute Battalion, spent

six weeks learning to pack their ’chutes,

practicing ground tumbling, and jumping

off low platforms to get the hang of landing.

The first real jump, however, was from a

plane. Now, with the building of steel train-

ing towers—similar to the parachute jump

at the New York World's Fair—the men

will begin jumping from the tower as soon

as they learn how to land. The pioneer

Marine ’'chutists have been using a tower

at Hightstown, N. J.

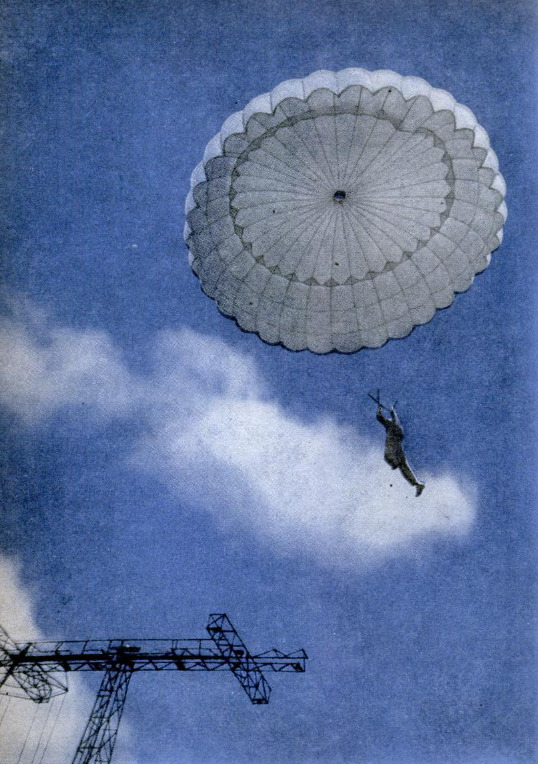

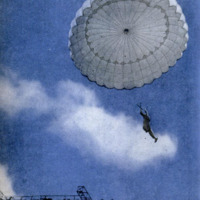

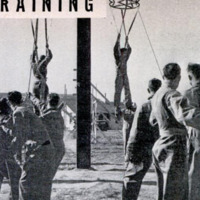

AT FIRST, wires guide the ‘chute straight

down, although the trooper wears rog- |

ulation harness instead of sitting in a swing +

seat checked by springs, as Visitors did in |

the World's Fair jump. ‘After two or three 1

“captive” jumps, Pete starts making “fly

away" jumps {rom the tower. |

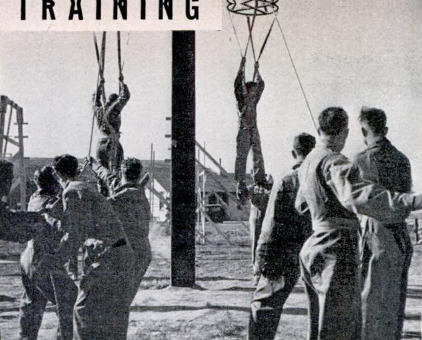

The novice Is now taught to grab the

risers, webbing attached directly to the sus- |

pension lines, and twist his body so hell |

face down wind, Otherwise, in landing, the |

“chute ia likely to pull him over backward. 1

He i8 also taught to pull up on the risers

Just before landing to cushion his fall. The

Jar Is equal to a Jump from a 41% to six-foot

fence.

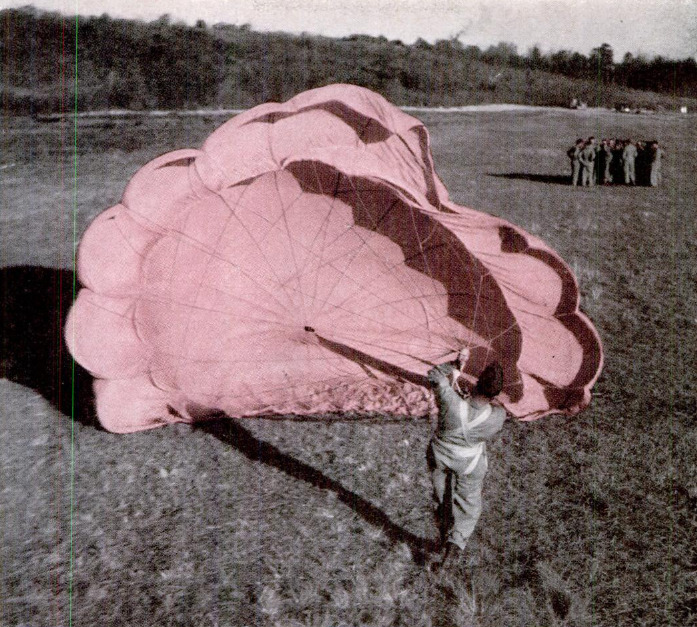

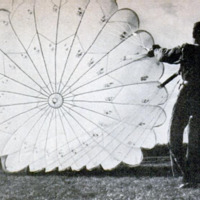

Before ho ever jumps from a plane he |

must also learn how to collapse his ‘chute |

after landing, by grabbing one or more sus- 1

‘pension lines and pulling it in fast until he

can catch hold of the canopy. He then sits |

down on as much of the canopy as he can

grab, and keeps on pulling it in. Even in

a 1‘mile wind, which ls just a breeze, n 1

fully inflated parachute will pull a man off

his feet and drag him.

In the Army, the Initial jump from a

plane is made with the static-line ‘chute, i

although the parachutist is taught to use

the rip-cord type as well. In all practice 1

Jumps Pete will wear two packs, the reserve

one being of the rip-cord type. Ho makes

his first jump at an altitude of at least

1500 feet in relatively still air. Before

stopping off into the blue, he and hi bud-

dies fasten static lines attached to thelr |

“chutes to a wire running along the side of |

tho plane, above their heads. His weight |

Jerks the “chute open, and the line breaks

away. I

Later he has to jump in a 35-mile wind,

and land in water, in a tree, and on top of

a building. Before landing in a high wind 1

or in the water, he must unsnap the harness |

around his legs and on his chest, then fold

his arms, to hold everything In place. As

his feet touch land or water he throws his

arms above his head, and the ‘chute is

blown free of him. He is taught to sideslip

away from trees or buildings, if possible.

When landing in a tree is unavoidable, he

must keep his legs tight together and kick

away from the tree, so that only the

canopy will get tangled in the branches.

The equipment of a parachute battalion,

made up of 34 officers and 412 enlisted men,

includes 386 pistols, 335 short-barreled auto-

matic rifles, or carbines; 30 sub-machine

guns, 27 .30-caliber machine guns, nine .60

caliber mortars, 30 folding bicycles, six au-

tomobiles, three motor cycles with side cars,

two half-ton trucks, and five 1-ton trucks.

Obviously a trooper cannot carry a .60

caliber mortar down with him. In actual

service he probably won't even carry a car-

bine, though the Army is experimenting

with the idea. A pistol, perhaps two or three

hand grenades, and a light silk rope for

letting himself down from a roof or tree

may be all Pete, the parachutist, will ever

take down with him.

Cargo "chutes will float carbines, machine

guns, mortars, and folding bicycles to the

ground. So troops will know which "chute

is which, the Army is experimenting with

red, blue, and yellow cargo canopies. The

Army is also experimenting with sky-blue

‘chutes and smoke bombs to screen para-

chutists.

Since it is essential that the parachutist

land as close to his equipment as pos-

sible, and also that, in many instances, a

number of men land fairly close together,

the Army flies transport planes as slow as

possible while the men are going over the

side. The pilot lets down the landing gear

and uses the landing flaps to slow up. Some

flights are even made with the plane doors

off, to break the streamlining.

Once the parachute soldier has landed

and picked up his equipment, he takes cover

and fights like any other infantryman. So

during the three months it takes to train a

regular infantryman as a parachutist, he

continues to practice digging in and taking

cover, as well as target shooting.

ENJAMIN FRANKLIN was the first to

B propose the use of parachute troops, in

1784. The Russians got their idea for air in-

fantrymen from experiments first conducted

by the U. S. Army nearly 20 years ago.

The U. S. Army organized its first para-

chute company only last summer after the

Nazi invasion of the Low Countries. The

air infantry’s work has progressed so well

that the force is being expanded to include

between 4,000 and 6,000 men. The Marines

also are expanding their parachute forces,

first organized last fall.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Walter Holbrook (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

88-94

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941

Screenshot_1.png

Screenshot_1.png Screenshot_2.png

Screenshot_2.png Screenshot_3.png

Screenshot_3.png Screenshot_4.png

Screenshot_4.png Screenshot_5.png

Screenshot_5.png Screenshot_6.png

Screenshot_6.png Screenshot_7.png

Screenshot_7.png Screenshot_8.png

Screenshot_8.png Screenshot_9.png

Screenshot_9.png Screenshot_10.png

Screenshot_10.png Screenshot_11.png

Screenshot_11.png Screenshot_12.png

Screenshot_12.png Screenshot_13.png

Screenshot_13.png Screenshot_14.png

Screenshot_14.png Screenshot_15.png

Screenshot_15.png Screenshot_16.png

Screenshot_16.png Screenshot_17.png

Screenshot_17.png Screenshot_18.png

Screenshot_18.png Screenshot_19.png

Screenshot_19.png Screenshot_20.png

Screenshot_20.png Screenshot_21.png

Screenshot_21.png