-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

America's air hitting power

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: America's air hitting power

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THIS country’s exponents of an inde-

pendent striking force of the air, co-

equal with the Army and Navy, sub-

scribe to the fighter’s traditional adage that

the most effective defense is a vigorous

offensive. Translated into terms of safe-

guarding the Western Hemisphere from

foreign attack, this means that they believe

in employing long-range bombers of the

“flying fortress” type to prevent any inva-

sion of the New World instead of attempting

to deal with it after it has occurred. Conse-

quently, they look with grave foreboding

upon a national policy—so far as the United

States can be said to have formulated one—

which ignores this principle in practice

though accepting it in theory.

Even the present world crisis, with its

brutally clear lessons on the effectiveness of

air power, has not served to clear the public

mind, or the minds of those directing our

defense program, of dangerous misconcep-

tions concerning this new form of warfare.

There is no lack of either popular or official

support (clamor might be a more descrip-

tive term) for “a strong air force.” But the

prevailing conception of this, among all but

the nation’s airmen, is, unfortunately, a

rather vague picture of swarms of airplanes

darkening the skies. It is a comforting pic-

ture to those who have it—or would be, if

only the airplanes would materialize—be-

cause they still visualize air warfare as a

battle in the air between opposing aircraft

and not as warfare waged from the air.

The heroic and spectacular performance

of the Royal Air Force in the “Battle of

Britain” probably has strengthened the

American public's misunderstanding of what

constitutes real air power. In its admiration

for the daring and courageous air fighters,

who were officially admitted to be the only

thing standing between Great Britain and

complete disaster ater Germany began her

aerial blitzkrieg, the public has almost com-

pletely lost sight of Britain's dire need of a

greater air striking force—hundreds and

thousands of bombers to blast German fly-

ing bases and hammer, far inland, at the

heart of her industrial war economy.

Too many people, some of them sitting at

our own defense councils, have been led to

forget that the British problem of coping

with air attack is totally different from that

of America, and this has added to the con-

fusion of our already muddled air-defense

thinking and planning. Merely because Spit-

fire and Hurricane pursuit planes were Eng-

land's salvation in the early days of Hitler's

“total” air war, it does not follow that

America’s safety lies in building swarms of

pursuit ships. Yet our Western Hemisphere

defense plan, as laid down by the Army's

General Staff, and approved by the Presi-

dent, called for 35 percent of all the air-

planes involved to be in the pursuit category

Champions of real air power, as applied tc

American defense needs, viewed that pro

portion as appalling. However, there is rea

son to believe that it is now being scaled

‘downward.

“The pursuit plane,” said one Army air-

man recently, “is, like the Army itself, in-

valuable for the close-in defense of our

borders, but it does not contribute one iota

to the air power of this nation. Air power

is proportional to numbers and types, not to

numbers alone. Fifty thousand pistols are

useless compared to a single rifle at a thou-

sand yards range. The pursuit plane is the

pistol of the air, while the long-range bomber

corresponds to the rifle. Why wait for your

enemy to get within pistol range, particu-

larly when you enjoy a geographical posi-

tion which makes it impossible for him to

use even his rifles against you until he does ?””

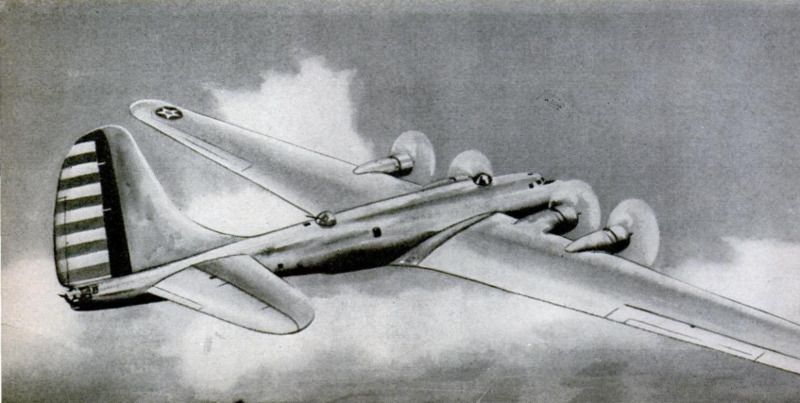

Long-range, four-engined bombers of the

“flying fortress” type, with an effective op-

erating radius of 1,000 to 1500 miles, are

the backbone of the independent air striking

force, as conceived by the proponents of a

cosrdinated land, sea, and air defense pro-

gram. They would be supplemented by

shorter-range medium bombers in some-

what larger numbers, with an operating

radius of 500 to 750 miles, and by light

attack bombers with a 250 to 375-mile

radius, as a third line of aerial offensive-

defense.

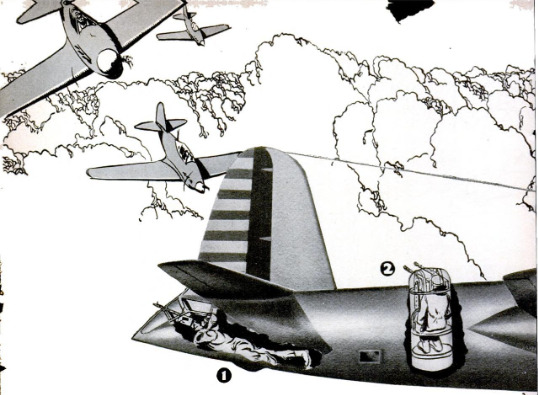

The theory of the employment of these

three types is that they would attack enemy

warships, aircraft carriers, and troop trans-

ports, three, two, and one sailing days re-

spectively, from the coastline or advanced

bases whence the bombers were operating.

It is self-evident that the nation’s “air

frontier” is extended under this system by

just so many sailing days as its air base

outposts are distant from the mainland.

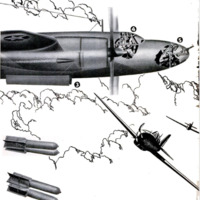

One tremendous advantage enjoyed by the

flying fortresses, and shorter-range bomb-

ers now being built to supplement them in

this type of air warfare, is that they will

be faster than any carrier-borne foreign

pursuit plane, so far developed, which might

be brought into action against them at sea.

Thus, they are virtually invulnerable to air

attack so long as they succeed in their

fundamental mission of preventing enemy

air forces from reaching and establishing

themselves in New World bases. This ad-

vantage, of course, will be lost in the case of

the flying fortresses released to Great Brit-

ain, which will be exposed to swift, land-

based German pursuit ships having a sub-

stantial edge on them in speed.

In order for an aircraft carrier's planes to

attack seaboard objectives, it is necessary

for the mother ship to launch them close

enough inshore so they will have sufficient

fuel not only to carry out their mission, but

to overtake and rejoin the carrier as she

steams back out to sea. Roughly, the off

shore launching distance figures out to 300

miles. Since a carrier can cover approxi-

mately the same distance in a ten-hour

night's run, it is obvious that such a vessel

must not be more than 600 miles from her

objective by sundown of the preceding day,

assuming that her planes are to be launched

at dawn. Consequently, a thorough daylight

air patrol of the 600-mile zone insures a

one-day warning of such an attack, if not

the certain destruction or disabling of the

carrier; while a 1,200-mile patrol provides a.

two-day safeguard. In either case, of course,

bad weather and poor visibility might enable

a carrier to slip in and deliver a serious

attack.

Alir-defense tactics of this nature already

have been worked out by the General Head-

quarters Air Force of the Army, which was

created several years ago as a half-hearted

step in the direction of an independent

striking force of the air, but is still subject

to the limitations imposed upon it by a

ground command. Such tactics would be put

into as full-scale effect, in the event of war,

as the limited flying equipment now pos-

sessed by the G.H.Q. Air Force would per-

mit, and presumably would be codrdinated

with offshore patrols of the Navy's air

force.

However, the Army and Navy high com-

mands hold many divergent ideas concern-

ing the employment of aviation in warfare;

known jealousies exist between the two

services, and there is too little assurance of

the most effective air teamwork possible

between them if a real defense crisis occurs.

This should not be construed as

any slur at able and efficient offi-

cers who head both the Army

and Navy; it is simply an ap-

praisal of their unswerving de-

Votion to the traditions of their

respective services and of their

limited-horizon concept of air

power as still being in its swad-

dling-clothes role of an “auxil-

iary service” to land and sea

forces.

Accepting the fact that Amer-

ica’s air power, for the present,

is still controlled by men with-

out thorough understanding of

either its limitations or possibili-

ties, an examination of the coun-

try’s present and projected air

strength, together with plans

for its use in a real national

emergency, would seem to be in

order. At the moment, the Army

has approximately 3,000 air-

planes of all types, including

training ships and obsolete com-

bat planes; the Navy total is

about 2,500. By July 1942, under

plans approved by the National

Defense Advisory Commission,

the Army is scheduled to have

an overall total of 18,000 planes

and the Navy 7.000.

Nearly half of the Army's

proposed 18,000 airplanes will be

trainers, because the Air Corps

faces the necessity of turning

out five times the number of

pilots it started with last sum-

mer, as well as acquiring five

times the number of aircraft

then on hand. Corresponding

Navy proportions are somewhat

lower, because the Navy tradi-

tionally manages to keep abreast

of its current needs better than

the Army, with the result that

its air force is not undergoing

so extensive an expansion. The

Army's present strength in com-

bat planes totals about 1,300; of

these 1,000 are obsolete types by

our own standards, and the other

300 would be “suicide crates” in

Europe's war because they are

not yet equipped with protective

armor plate for the crews, or

self-sealing fuel tanks, and because they

lack adequate gun power.

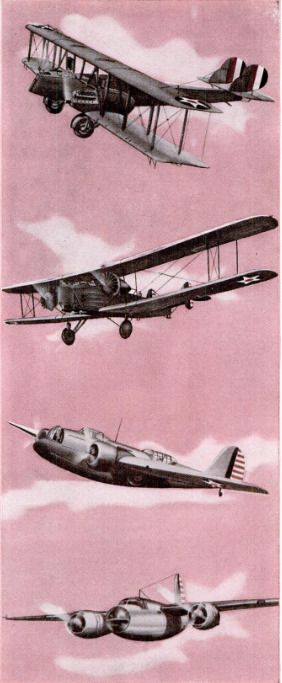

A breakdown of the Army's strength in

combat aircraft “on hand and on order”

shows that it now has, in round numbers,

100 long-range, four-engined bombers as a

nucleus for its projected fleet of at least

1,000 such ships. In the two-engined me-

dium-bomber class, it has 350 ships of a

woefully outmoded type, and plans for 1,500

such craft of modernized design and per-

formance. In the light attack-bomber field

it now has nothing at all, but has placed

orders for 1,200 twin-engined craft of this

type. On the pursuit front, the Army could

muster some 650 obsolete ships and 200 of

modern design—barring the fact that they

have not yet been brought up to the Euro-

pean standards previously mentioned—and

expects to have a total of 2,000 to 3,000.

In the non-combat field, it is interesting to

note that the Army, profiting from lessons

learned in Europe, will procure 2,000 twin-

engined observation planes to replace pres-

ent single-engined ships of this type now

considered useless in modern air warfare.

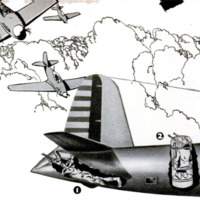

Besides training and combat types, the

Army's plans call for some 500 transport

planes of either the four-engined or super-

twin-engined type, capable of carrying 20

soldiers each, with full arms and equip-

ment for 24 to 36 hours combat operation,

on nonstop flights of 1,500 miles. These air-

craft, however, probably won't be delivered

until 1943. What they will mean is the

ability to concentrate a highly trained land

force of 10,000 men on short notice at any

“danger zone” in the Western Hemisphere

where suitable landing fields are available.

Hence the importance of the various air

bases which the United States is now striv-

ing to acquire at strategic points through-

out the New World. Anyone with a map and

a ruler can figure out about how many such

bases are needed and where they should be

located. Nor does it require a military

master mind to see the seriousness of allow-

ing a hostile force to establish itself at such

bases within air striking distance of the

United States or its defense outposts.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

C. B. Allen (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

113-117

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 4, 1941