-

Titolo

-

Pursuit pilot

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Pursuit pilot

-

extracted text

-

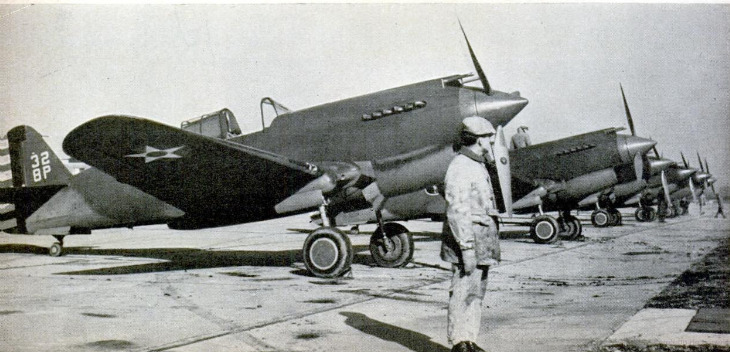

THE six little planes became visible

eis as a string of tiny dots, and

almost immediately were circling

around the field. They swung around in

their traffic pattern at 1,000 feet. Then the

leader dropped off, came down in a short,

tight spiral, sideslipping all the way to

lose altitude quickly. He set the fast Curtiss

P-40 down as gently as a baby, and one

after another the five other planes swooped

down beside him. They bounced a bit, but

out of that great military airport they

had used only about enough space for a

cabbage patch. And it was as quick and

flashy as a flight of swallows swirling

around your house and diving down the

chimney.

“That ought to be Phil Cochran now,”

said the public relations officer. “He is

due any minute now, and that looks like

his group.”

This was at Mitchel Field, Long Island,

which the Army Air Corps had recently

changed from a bomber base into a fighter-

plane field for the protection of New York

City. I had come out there that morning

and said I wanted to talk to pursuit pilots,

especially to some of the kids who had

recently been flying cadets at Kelly Field.

If it takes two years to make a military

pilot, and three years to make a good one,

as all the experts say, then there must be

a lot these boys can tell about their job.

Stuff we all want to know; for, after all,

these lads are the American version of the

Hurricane and Spitfire boys Who so recently

have rescued civilization.

Now the six planes came taxiing across

the field toward the hangar, swirling up a

great cloud of dust behind.

“Cochran is the man for you to talk to,

all right,” said the officer. “He's been break-

ing in a bunch of the kids. They call him

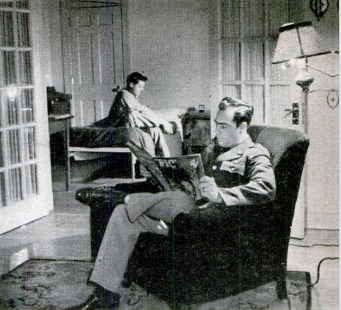

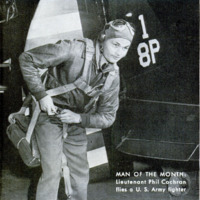

Cocker.”First Lieutenant Philip G. Cochran, flight

leader in the 33rd Pursuit Squadron, when

he had unzipped his heavy flying suit of |

leather and lambskin, turned out to be a

pink-faced little youngster with dark, curly

hair, a wide smile, and vast enthusiasm for |

his job. He came from Erie, Pa., and was

graduated from Ohio State University in

1935. He has been in the Air Corps five

years, and I was surprised to learn he was

31 years old, which is above the average.

That was because, what with the depression,

it took him six years to get his college

degree. He worked his way through, by

singing in a dance band.

After he had attained that seemingly im-

possible college degree, Cochran felt ready |

to tackle something else impossible, so he

put in for appointment as a flying cadet.

He told me later he never felt so futile or

silly in his life as when he went in for the

physical exam. Before him was an inter-

collegiate wrestling champion and behind

him was a Big Ten football star, and he felt

very insignificant beside their manly torsos.

But the wrestler's blood pressure Was too

high and the footballer was muscle-bound.

The crooner got through.

Phil Cochran would be horrified that I.

am writing about him thus personally, but |

it has to be done. You can't separate fighter

flying from the pilot's personality. In the

late stage at Kelly Field they pick the boys |

out for specialties. Sound, careful pilots

go with the Regular Army for observation

work. The brainy boys with executive abil-

ity and a flair for navigation and technical

matters are picked for bombardment, to

drive the big freight trains. To be a pursuit

pilot you've got to be a motor-cycle rider

or an outboard motor-boat racer at heart.

You've got to be scrappy, and you've got

to be small.

Phil Cochran stands five feet seven and

weighs 147 pounds. That's just what he

weighed when he enlisted. He's kept it by

playing a lot of squash when on the ground.

The man who is sluggish will black out

quicker than one who gets a lot of exercise.

Blacking out is what happens when, in a

quick turn, centrifugal force drives the

blood from your head. You see red, then

gray, and then you are unconscious for a

moment.

The pilot who blacks out last has an ad-

vantage, but there's nothing wrong about

blacking out. In an ordinary morning's

routine rat race behind Phil Cochran the

boys go black four or five times. If you

don't do it you aren't flying the plane right,

for the best plane in the world is second-

rate if it isn't delivering every ounce of

performance. That's where mental attitude

and personality come in. The boys say

Cocker is good because he drives them every

moment in the air. When he takes a flight

on a mission, he never goes right there and

back. At any instant, he is likely to pick

out a target and dive for it; and you've got

10 be right there in the formation with him.

They say Cocker always takes a flight off

and lands it as if they were using a small

‘emergency field in the midst of battle.

The youngsters working with Cochran

think they are very lucky to learn from a

man with such aggressive flying habits, for

fighter flying is largely a state of mind—

straining’ always at the limits of speed,

maneuver, and precision. Having learned

such habits, they will be able to pass them

on to other boys who will be pouring into

the Air Corps. And it is this matter of

attitude, of never taking it easy, which

makes the difference between a fighting

squadron and a collection of aviators.

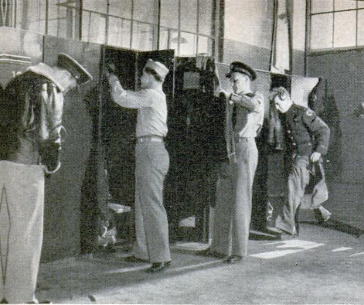

The 33rd Pursuit Squadron's latest batch

of new officers joined it in September. They

had just received their wings and commis-

sions, after three months (65 hours) of

flying in primary trainers with civilian in-

structors, three months (70 hours) at Ran-

dolph Field in basic trainers, and threo

months (another 70 hours) at Kelly Field

in advanced trainers. They had had an

easier time than prewar classes, for the

Corps is not eliminating so many nowadays,

but they were well-trained flyers who had

been through a stiff course. Now they were

at the most difficult point, the transition

to a tactical airplane.

Lieutenant Cochran took those assigned

to him and set each of them in the cockpit

of a P-40, let him sit there for an hour just

getting familiar with it. The new man was

fresh from flying a fine, sensible airplane,

of 450 horsepower, less than 200 m.p.h. max-

imum speed. Now he was going to fly one

of the newest of tactical planes, the one

known to the British as the Tomahawk. It

had a 1,000-horsepower liquid-cooled Allison

engine, would do more than 300 miles an

hour. It was a further development of the

plane which made that famous dive last

year, at 575 miles an hour. There was no

seat for an instructor. The new man had to

fly it alone.

The big hurdle was psychological. The

most important thing about flying a pursuit

plane is to have perfect confidence that you

are its master. Cochran took the boys one

by one and sold them the idea that they

could fly the P-40. It was like talking to a

man who has learned to ride a gentle saddle

horse, and persuading him that he was

ready to tackle a bucking broncho.

Then the first flight. Once the new man

was up in the plane, his problem was how

to get down, and he probably felt out the

plane for a half hour before trying that.

There were a number of things to try out.

For instance, he had to gain a lot of altitude

before he could open up the throttle wide;

for the Allison is built to fly best at high

altitudes; if you open her up at the atmos-

pheric pressure of ground level, you'll ex-

ceed manifold pressure; she'll get hot and

quit on you. Then there was the variable-

pitch prop control to try out; the Allison

runs at constant speed; you use increased

power by taking a bigger bite of air with

the propeller. After gradually putting her

into a stall a couple of times, to try out

minimum gliding speed, he took the bit in

his teeth and brought her down.

Three flights the first day were the transi-

tion pilot's quota. After ten hours of transi-

tion flying, he was ready to try some sim-

ple maneuvers in formation. No matter how

good you are to begin with, it takes 50

hours flying one of these planes before you

can throw it around.

The first thing about formation flying is

to come in close, and stay put. The first two

that went up with Phil Cochran came close,

but not close enough. He put up his index

finger and waggled it in a come-hither ges-

ture. They were close enough to see the

finger waggle, but he wanted them a lot

closer. That takes nerve and confidence at

pursuit-plane speed. But before this year is

over each of these boys will be flying in a

squadron formation with planes both above

and below him, with no more than a few

feet clearance. At times, he won't be able

to see the plane below him, of course. But

he will know right where it is, because it

is precisely aligned with the planes on either

side.

These three planes had two-way voice

radio, of course, but Cochran didn’t use it

much. In battle, radio may go out of com-

mission. Also, if you are getting ready to

attack a bomber which hasn't seen you yet,

you don't want to discuss it on the air.

Right from the start you learn to rely on

signals, and on following the leader.

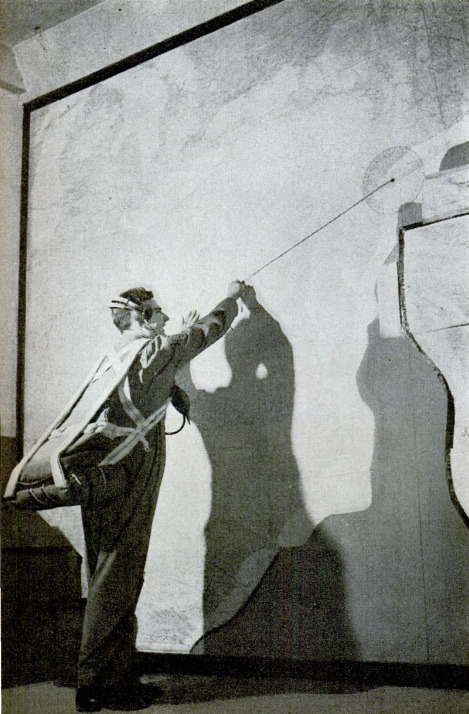

Formerly, pursuit pilots signaled by stick-

ing an arm out of the cockpit, in a sort of

semaphore. But cockpits are closed now;

and, anyway, the man who stuck his arm

out of & plane at 300 m.p.h. would wish he

hadn't. Signaling now is done by the lead-

er's plane itself, and there are three basic

signals:

Tail wiggle (a horizontal movement, done

With the rudders). In V formation, this

means “Get into string.” In string forma-

tion It means “Go nto V.""

Wobbling wings (done with ailerons).

This means “Build up to larger formation.”

Up-and-down tail hop (down with the

stick). This means “Break down to the

next smaller unit and follow the leader.”

This also is the signal for landing, It the

leader lands.

In the Sth Pursult Group they use another

signal, the quick wing wobble, practically

a vibration. In string formation, this means

“Make company front.” It also means “At-

tention, watch what I do, be ready.”

‘They've been telling a story of what hap-

pened in a recent three-ship training fight

in Texas. The leader's engine began going.

bad, and he jerked the stick back and forth

t0 try to Jolt the carburetor into action. The

trick didn’t work. The engine went dead. So

he picked a spot and landed. Fortunately he

was safe. Then he looked around to see

what had become of his companions. They

were sitting there in the farmer's field be-

side him. They had seen his tail hop and

followed him down. That is what is called

air discipline. The story does not tell what

the two trainees were thinking as they fol-

lowed the dead engine.

You will notice that none of these signals

has anything to do with turns, banking,

loops, and other things most of us think of

as combat maneuvers. For these there are

no signals. They are merely a matter of

following the leader. If you think a girl is

good when she follows her partner on the

dance floor, then consider the pursuit flyer,

who has to do the same thing with precision

multiplied a thousandfold, in a plane going

five miles a minute. His attention is glued

on the leader, until he follows him automati-

cally, with split-second accuracy. In a very

real sense, the leader flies his whole forma-

tion.

After Cochran had got his two pupils

in close, he made a quick turn to the left

and lost them. Sure enough, the man at

the right (the outside) fell behind. The in-

side man, at the left, dropped down. What

they must learn was to go right around

with him, sticking right in their places.

They tried again, and this time he used the

radio a little. “Come on, give more gun,”

he said to the man at his right, who had

to travel farther, being on the outside. This

time he got it, held himself right there by

the leader's wing, as they went around in an

almost vertical bank.

When a company of foot soldiers turns

column right, the man at the right of each

squad pivots, practically marking time at

the turn. But airplanes can't stop that way,

and when they turn, they all have to start

at practically the same instant; they don’t

go around a corner. Theirs is a fluid maneu-

ver, and they are able to equalize the dif-

ferences between inside and outside turns

by using the third dimension, and also by

crisscrossing their courses.

Formerly when three planes were flying

a turn, they crossed over in this same fash-

fon, to equalize the distances. But today's

planes maneuver so well that when flying

in threes they no longer cross.

The boys learned various special things

at this period. They had to work on cross-

country navigation, for in a fast plane you

are likely to get lost. They worked at night

flying. They made a maintenance flight to

a strange base, away from home mechanics,

learning the routine of taking care of their

planes, There were many special tricks they

had to learn about flying these fast ships.

For instance, putting down the retract-

able landing gear. To lower the wheels you

have to cut down to 170 miles per hour. But

you need to maintain power, because the

mere lowering of the wheels slows the plane

down 50 miles per hour. So the leader dives

and pulls up, to lose speed without reducing

the throttle. Then the wheels go down, and

another dive picks up speed again, while the

pilots check up on cach other's wheels, nod-

ding to each other through the glass hoods

covering their cockpits.

As the new men began to be able to throw

their planes around in formation flying, they

would go up in larger groups. Every day,

going up on the regular morning flight, they

would first go into string and then have a

rat race. A rat race is something few of us

will ever see, for like a dog fight it goes on

at high invisible altitudes, and is too fast for

effective photography. It is, really, a simple

game of “follow the leader” in fighter planes.

The leader does everything he can think of —

Immelmanns, loops, snap rolls, and turns,

always turns, tighter and tighter. To the

fighter pilot the turn is what the left hand

is to the boxer. In a dog fight the man will

win who can turn inside the other.

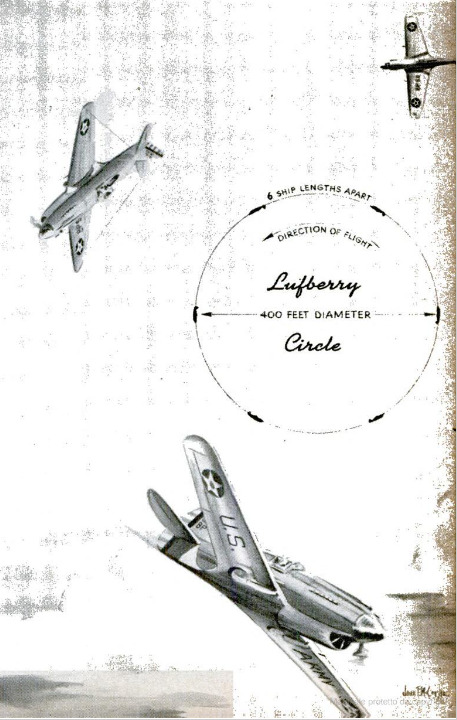

After rat-racing until everyone was tired,

they would practice the Lufberry circle.

Invented during the World War, this ma-

neuver is the great, fundamental defense

formation of pursuit planes. 1f a flight of

fighters finds itself hopelessly outnumbered

by enemy pursuit ships, it goes into the

defensive circle.

1t is almost impossible to shoot down one

of these fast modern planes from the side,

because it is moving too fast. The attacker

must get on the tail of his quarry to be

successful, and fire from fairly close range

with the guns fixed in the leading edge of

his wings. But when planes are in the de-

fensive circle, each one is protecting the

tail of the one ahead. The attacker can’t

get a good shot without exposing his own

tail, and if he keeps away, his shots go

ineffectually tangent to the circle.

The telephone rang. Lieutenant Cochran

was wanted right away at Operations.

Meanwhile, waiting for a chance to go on

with our conversation, I talked with some

of the youngsters he had been training.

They had been in the Air Corps more than

a year now, had been second lieutenants

with wings for four months. But still they

had not progressed beyond the ABC stages

which have been described in this article.

These boys were all eagerness to get on

to their next steps—dogfighting, gunnery,

and tactics. I was eager to learn about

these things too, and eventually did. But

meanwhile I had begun to realize why it is

you can’t make a military pilot in a year's

training, no matter how intensive. And I

realized you can’t tell about it all in one

short article, either. I'll tell you more about

it next month.

-

Autore secondario

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-05

-

pagine

-

52-58,220

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik