-

Titolo

-

How homes can be protected from air attack

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: How homes can be protected from air attack

-

extracted text

-

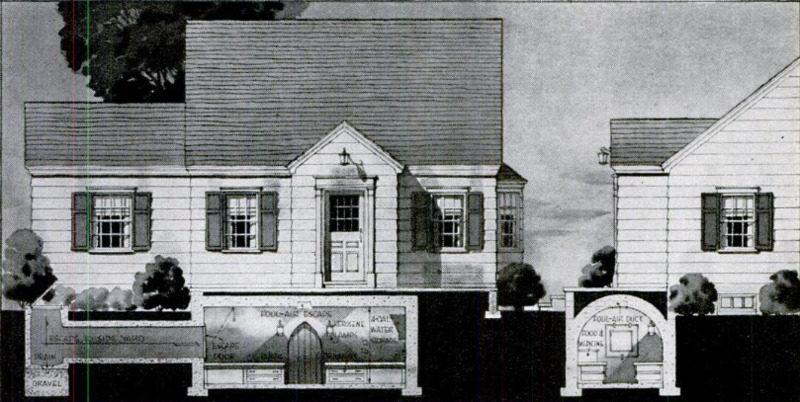

BY BREAKING DOWN the hours of work

and leisure of the average citizen it has

been estimated that the chances are better

than three out of five that an enemy bombing

attack will take place while he is at home,

Thus, protection of the home and those with-

in it becomes of paramount importance.

There are five general types of shelter

a home owner may use, and his choice will

depend on such considerations as expense,

ease of construction, comfort, and vulner-

ability. These types, shown on the following

pages, are:

1. A refuge room, within his

home.

2. An open trench in his yard.

This is good protection against

blast and splinters from a high-

explosive bomb, but is no protec-

tion against gas or falling splinters

from an antiaircraft shell, and is

a miserable makeshift in inclement

weather.

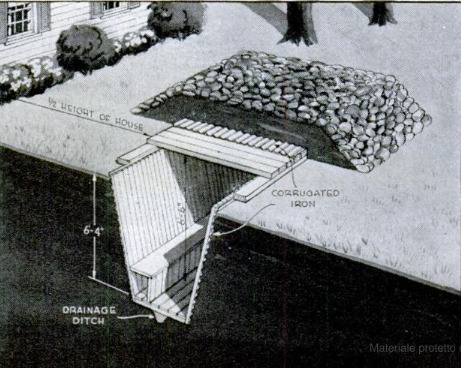

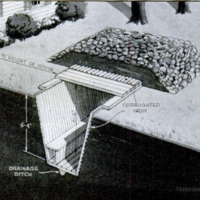

3. A trench dug at least 6 feet 6

inches in the ground, with side

walls of planks or corrugated iron

and covered with 2 to 21% feet of

earth supported by planking or

corrugated iron. For the sake of

safety from a direct hit on the

home, such a trench should be built

at least half the distance of the height of

the walls away from the house. This trench

is safer than a room in the house, but is apt

to be uncomfortable.

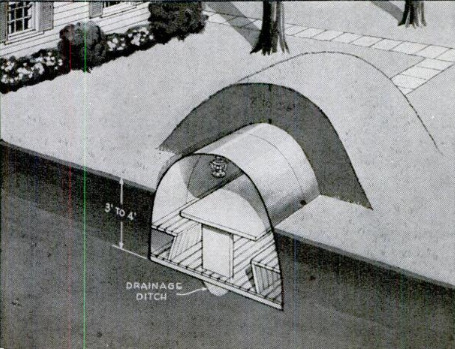

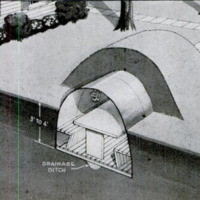

4. A semisurface type of trench, like the

Anderson type in use in England, formed

by placing preformed arched sections of

sheet steel or reénforced concrete in a

trench 3 or 4 feet deep and covering the

sections with earth to a depth of 2 to 21%

feet. These give as much protection as the

covered trench, but are more expensive and

suffer the same disadvantages of discomfort.

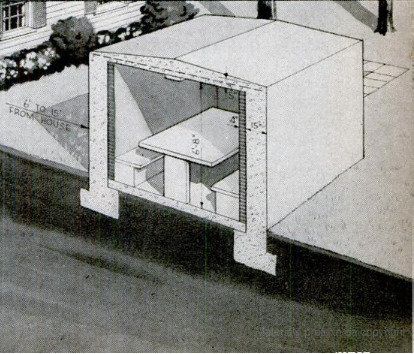

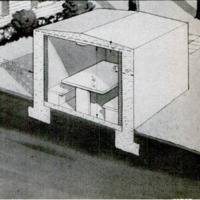

5. Shelters that are essentially pill boxes,

built on the surface of the ground of con-

crete or brick. The external walls should

be 13% inches standard brickwork, or 15

inches of sound concrete; the interior walls

should be 4 inches of brickwork and the

roof should be built of 5 inches of reénforced

concrete. They should be placed within 6

to 15 feet from the house in order that the

walls of the house may serve as additional

blast protection. These shelters are com-

fortable, dry, but expensive.

The required standard of overhead pro-

tection against blast and fragments from a

500-pound bomb bursting 50 feet away is

afforded by: 1/4 inch of mild steel plate;

4 inches of reénforced concrete; 6 inches of

ordinary concrete; brickwork or masonry

arches of not less than 8 1/2; inches crown

thickness; or 18 to 24 inches of earth,

sandbags, ballast, or broken stone. If im-

munity against direct hits of the most

frequently used bombs (ie, up to 550-

pounds) is desired, the overhead cover of

the shelter must be increased to a minimum

of 7 feet of reénforced concrete.

Since protection on Lhis scale tor large

numbers of people would involve immense

cost, it is considered impracticable for gen-

eral use, and the first-mentioned standard of

overhead cover is the one most widely used.

The required standard of lateral protection

for outdoor shelters is secured by 1 1/2; inches

of mild steel plates; 13 1/2-inch walls of good

brickwork (ie. 1 1/2 bricks thick), or sound

stone masonry; 12 inches of reénforced con-

crete; or by 30 inches of earth, sandbags,

ballast, or broken stone.

All these types of shelters, it should be

stated parenthetically, are not designed to

offer protection against a direct hit of a

high-explosive bomb, such as the general-

purpose bomb, the kind generally used

against urban areas. The heavier 660-pound

to 4,000-pound demolition bombs usually

are reserved for specific military targets,

and the smaller 22-pound to 55-pound

fragmentation bombs are designed for at-

tack on troops in the field.

Civilians have most to fear from general-

purpose, high-explosive bombs, which range

from 45 to 550 pounds; gas bombs, from

22 to 550 pounds, and gas sprays; and from

incendiary bombs, ranging from 2 1/5

pounds to 55 pounds. The small type, known

as the electron bomb, and consisting of a |

magnesium tube filled with powdered alumi- |

num and iron oxide, called thermite, is con |

sidered the most effective. One large bomb- |

er can carry from 1,000 to 2,000 of these

small incendiaries and scatter them over

a wide area. |

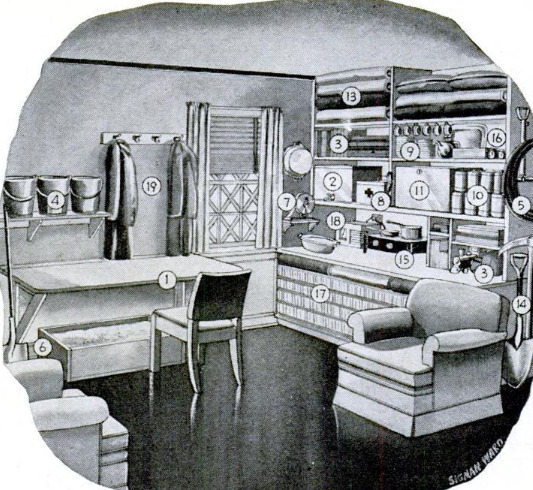

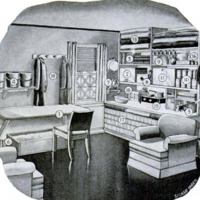

To the average house owner the refuge

room, for reasons of economy and comfort, |

has usually a greater appeal than any other |

type of domestic shelter. But if his house |

is of light wooden construction a refuge |

room will not afford the necessary amount |

of safety for himself and his family and he |

must choose one of the other types of |

shelter. For it requires 13 1/2 inches of |

brickwork to give full protection against |

bomb splinters and 9 inches of brick wall |

to stop the majority of splinters. |

Fortunately this does not mean that a

refuge room must be inclosed in 9 to 13%

inches of brick in order to be comparatively

safe. The thickness of all walls within 30

feet from the refuge room may be con-

sidered as added to the thickness of the

room walls. The house next door, for ex-

ample, if it is within the 30-foot limit, or a

high garden wall, could be considered as

part of the protection of a refuge room.

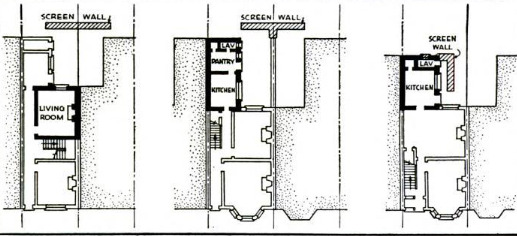

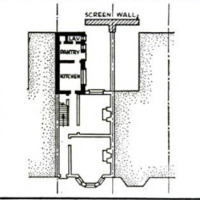

As a general rule, a refuge room in the

basement is preferable, since it affords the

best protection against blast and fragments.

In stories above the ground level there is

always danger that fragments from high-

explosive bombs falling near a building will

strike upward through a window below the

room and then through the floor of the

room. For this reason, when a refuge room

in the basement is not feasible, a protected

room on the ground floor is usually the best

location for a refuge room. The next-best

location is an inner room upstairs, but not

on the top floor. The guiding principle is

to choose a room that already is protected

as much as possible by surrounding walls

of brick, stone, or concrete, including those

of the house next door.

The most favorable place for a ground-

floor or upstairs refuge room is a corridor

or an inner room without windows, or a

room with a window facing a narrow court

or alley, so as to secure partial protection

from neighboring walls. Windows and doors

of refuge rooms which are mot already

shielded by another house or solid wall

within a distance of 30 feet must be

especially protected against bomb blast and

splinters by blocking them up, or by erect-

ing barricades around them outside the

building. In either case the protection

should be raised to a height of at least 6

feet above the floor of the room so that

occupants will be out of danger of splinters.

The simplest way to block a window or

door that is not needed is to brick it up with

good brick masonry, 1 1/2 bricks (13) thick.

A less expensive method is to build a

frame crate over the outside of the window

and fill it with earth, loose gravel, or

shingle, to a thickness of 24 to 30 inches.

The most effective method of protecting a

window against the blast of high-explosive

bombs is to construct around the outside of

the window sandbag walls or earth traverses

2 feet 6 inches thick, which must entirely

cover the window opening and abut the

brickwork with an overlap of at least one

foot all around.

The protection of windows is extremely

important, for gas may be used by the

enemy concurrently with high-explosive

bombs, and the shattering of the windows

would permit gas to seep into the room.

Where windows cannot be protected by

barricades it is necessary to reénforce or

replace the ordinary glass by some non-

shattering transparent or translucent ma-

terial such as celluloid, or cellulose acetate

applied with cellulose varnish to the inner

surface of the pane; or vitreo celloid ma-

terial, such as “cellatoid” reénforced by

1/2-inch wire-mesh netting, substituted for

pane; or glass internally reénforced by wire-

mesh netting; or finally by oil-impregnated,

gasproof blankets nailed over windows on

the inside.

A covering over the pane, such as tough

paper, cardboard, cloth, or cellophane, can

not prevent a pane from breaking when a

bomb explodes near by, but it can prevent

glass from flying about in dangerous

fragments.

As a general rule, a small or narrow room

is preferred for refuge purposes, provided it

has sufficient area and cubic space to meet

ventilation requirements, for the reason that

its roof or ceiling will be more resistant to

a load of falling debris than a room of

underspan. Where material and labor are

available for propping up the ceiling over

the refuge room, it is not so important to

choose a small and narrow room. Rooms

with large windows, and especially bay

windows, should, of course, be avoided.

An added precaution to exclude gas from

filtering into refuge rooms through bro-

ken windows is to attach to the inside of

the window a flexible shutter, hinged at the

top so that it will momentarily yield to

the blast impulse but return to an air-tight

position almost immediately. Such a shutter

may be made of wall boarding, plywood, or

other resistant material fixed to a light

wooden frame, accurately fitted to the win-

dow opening and having a rubber, felt, or

thick cloth strip tacked around its contact-

ing edges. The shutter should be held in

place only by its friction with the window

frame, 80 as not to offer resistance to the

blast impulse, but to swing freely and then

return to its position against the frame.

Since no serious amount of gas will enter

a room unless there are air drafts to carry

it in, all extraneous openings should be

stopped up. This can be accomplished by

filling all cracks and crevices in the walls

and ceiling with putty, or pulp made of wet

newspaper, or by pasting them over with

strong gummed paper. All trap doors, sky-

lights, and ventilators should be sealed, and

if there is a fireplace the flue should be

stuffed with rags, paper, or sacks; or better

still, the opening should be closed with a

sheet of plywood and adhesive tape.

Care should be taken to seal up all cracks

between and around window sashes, and

gas curtains should be fitted to all doors.

A gas curtain is constructed by fastening

a blanket with strips of wood on the outside

of the door frame, except for some 5 feet

above the floor on the side away from the

hinges. The bottom of the blanket is left

loose at that corner, so that it can be lifted

up to let a person through. About one foot

of the blanket is left trailing on the floor

to prevent air drafts under it. If the blanket

is impregnated with oil, it gives better pro-

tection.

If a refuge room is situated below the top

floor of the house, as it should be, there is

little danger of a direct hit by an incendiary

bomb entering the room, for such a bomb

does not penetrate a house below the attic

floor. The bomb must, however, be ex-

tinguished promptly, for the thermite burns

flercely at 3,000 degrees centigrade for

about one minute,

setting fire to the magnesium casing, which

burns for 15 minutes. All litter, lumber,

and paper should long since have been re-

moved from the attic and the woodwork

should have been made fire-resistant by

applications of two coats of whitewash, con-

sisting of slacked lime, one ounce of com-

mon salt, and a pint of water. Fire-fighting

materials—buckets of water and sand, a

long-handled shovel, and a hose and pump—

should be kept on hand in the refuge room.

Incendiary bombs can be extinguished

by covering them with sand and then lifting

them with a shovel and placing them on

top of sand in one of the buckets. Or a

spray—not a stream—of water can be

directed on the bomb, causing it to react

more violently and burn itself out in a short

time. The water method has its dangers, as

a stream of water played directly on a

bomb may cause it to explode and project

molten metal for 15 or 20 yards.

-

Autore secondario

-

A. M. Prentiss (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-05

-

pagine

-

77-80,218

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik