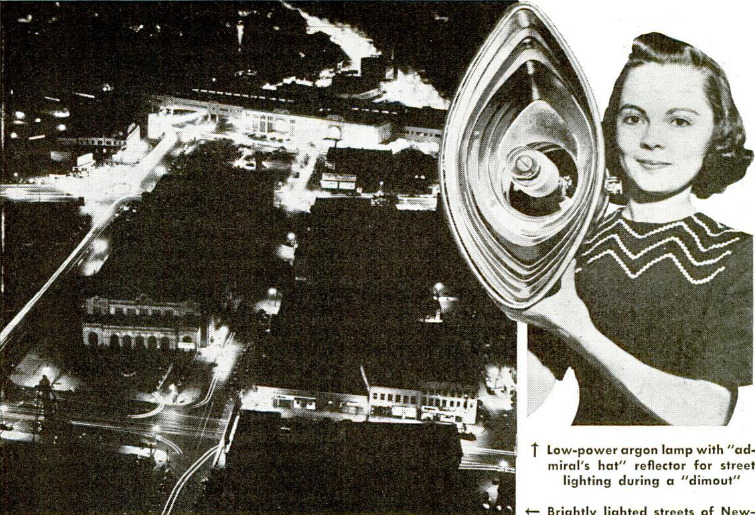

WAILING sirens send shivers down thousands of spines, and a great city swiftly and methodically resolves itself into self-imposed paralysis. Motorists caught in the blackout pull up to the curb and turn out all lights. Home windows are curtained, skyscrapers suddenly go dark, street cars grind to a halt, flashing neon signs vanish from the skyline one by one, and for a brief moment the only lights visible are the red and green dots of traffic signals. Then they, too, fade into the blackness and there is only an occasional stab of a flashlight or the flicker of a match cupped between hands to light a cigarette. In the coastal city the blackout is real; farther inland it may be only practice. Anywhere, it is eerie. At first the public, resentful of a neigh- bor's careless lights or a brilliant shop window or advertising sign neglected in the night “alert,” wondered why you couldn’t just pull a master switch in the power station and blacken the entire city. But it is not so easy as that. Alarm systems must not be disrupted by a power cutoff, elevators and electric stoves and heaters need not be. That is the reason for experimental blackouts in interior cities fairly safe from air attack. There must be order in the seeming chaos of darkness. For the ordinary citizen a blackout involves only inconvenience and a little discomfort. If he is driving his automobile he stops and extinguishes lights. If he is walking he can stumble on in darkness or wait until the lights come on again. If he is at home he simply puts out the lights or blankets the windows. Or he might follow the example of Henry Prescott, paint company executive, who has outlines in luminous paint the tables, chairs and other objects in his Mt. Kisco, N. Y., home. This makes them faintly visible at night when all lights are turned out, and permits most ordinary activities to be continued during the blackout without going to the trouble of curtaining the windows. Luminous paint has been widely used in Europe, but generally on outdoor objects. The real problems of a blackout are those of police and fire departments, transportation companies, hotels and electric utilities. The life of a big city cannot stop entirely even for a 15-minute period. Even before the sirens give the “lights out” signal, a load dispatcher at the power house of the electric company is watching the indicator to see how much electrical energy his generators are furnishing to customers. The indicator has been dropping slowly for nearly an hour as people have been turning out lights and going to bed. Then comes the strident wail, warning of danger. Trolleys stop. Lights disappear. The indicator plummets downward. At Pittsburgh the Duquesne Light Company is said to have dropped about 75,000 kilowatts of clectric load when the practice blackout signal sounded. That isequivalent to about two million ordinary electric lights, more than the total load in many a small city. This load had to be picked up again immediately when the “all clear” sounded. As a matter of fact, the electric load picked up after a blackout is likely to be greater than that dropped at its beginning, as the simultaneous starting of street cars all over the city creates a specially heavy power demand. This problem is not new to the power companies. They have to handle sudden changes of load in their regular business. The load dropped during a blackout may, in fact, be less than that dropped during the noon-hour shutdown of a working day. Automatic machinery in the power station is designed to take care of such changes. When the load on the generators begins to declinte the draft blowers for the boilers automatically slow down and steam supply diminishes. When the load increases the blowers speed up and provide more steam. Transportation companies have more difficult problems. Special precautions must be taken to protect the thousands of people riding in the companies’ vehicles. During practice blackouts in Seattle, Pittsburgh, Newark and Toronto, all street cars and buses were halted to prevent accidents. But in a protracted blackout the procedure would probably be different, as there would be no way of foretelling the duration of the danger and you can’t stop transportation service indefinitely. In British cities the surface vehicles reduce speed during blackouts, but continue to operate with shaded lights until actual bombing begins. Numerous accidents have occurred as a result of this practice. Service was halted in Newark's 4 1/2-mile trolley subway during the trial blackout. Part of this route is under cover, part in an open cut, but the signal lights for both parts are on a single power circuit, and it was decided that the entire signal system should be turned off. This meant that the cars could not continue to operate, even under cover. London’s “Underground” keeps running during air raids. Its operation is somewhat hampered by the use of many stations as shelters, but most raids take place at night when travel is relatively light. Whatever might be done in this country about subway operations during an air raid, the use of subway stations as shelters would not be very satisfactory orsafe. Most subways are close below the street surface, and would be much more vulnerable in air attack than the deep-level tubes of the London system. Hotel managers scratched their heads in perplexity over the blackouts. Public rooms could be darkened by turning out lights or putting caréaflns over windows. Guests rooms, however; were ot under the management's direct control. To pull the main switch and plunge the whole building into darkness was considered impracticable. Though effective in results, it would hardly be in accord with the tradition that guests must be handled with tact; moreover, there would have been a considerable element of actual danger in suddenly cutting off all lights and stopping the elevators. Instead, the hotels distributed blackout notices to guests asking them to extinguish room lights or to pull down the curtains. Watchers outside spotted the windows that remained lighted and hurried messages were dispatched to those rooms to put out or conceal the lights. Fire and police apparatus are being equipped with shaded lights for use during alarms. In one city a guard was stationed at each fire alarm box in the downtown area to prevent any false alarms. At Seattle the police radio transmitter was cut off when a light switch was opened during the blackout. No messages could be sent from headquarters to the radio patrol cars. In another town, municipal authorities found they had 635 gas-burning street lights, each of which had to be turned off individually. At Toronto the fire sirens were used to give the blackout signals. When a real fire occurred in a blackout, sirens of fire apparatus responding to the alarm were believed to be the “all clear” and many lights were turned on again. While efforts here have so far been di- rected toward making blackouts complete, some authorities question the desirability of total darkness. Dr. Samuel Galloway Hibben, director of applied lighting for the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company favors “dimouts,” leveling lights to the quality of moonlight. “Total darkness during air attacks,” he says, “can cause more civilian casualties than bombs. Normal eyes require about 20 minutes to adjust themselves to blackness so that the faint outlines of objects can be seen it close range. Lighting of less than moonlight intensity does not make it any easier to find the city from the air nor to identify perticular spots, but it does help greatly in preventing accidents.” To maintain- essential traffic during air raids it has been suggested that police carry portable, shielded traffic lights strapped to their shoulders. A band of white is recommended for the bodies of autos and trucks with cat-eye slits in headlights and small running lights suspended under the chassis. Fluorescent paint excited by ultraviolet light can illuminate subway entrances, police stations, bomb shelters, hospital entrances, fire hydrants, crosswalks, curbs and clothing. Another development is a low-power argon lamp with a reflector which would prevent the light being visible from the air. Blackout or dimout, the problem is new to the people of the United States. We must learn what to do and what not to do when the sirens shriek.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 5, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 5, 1942