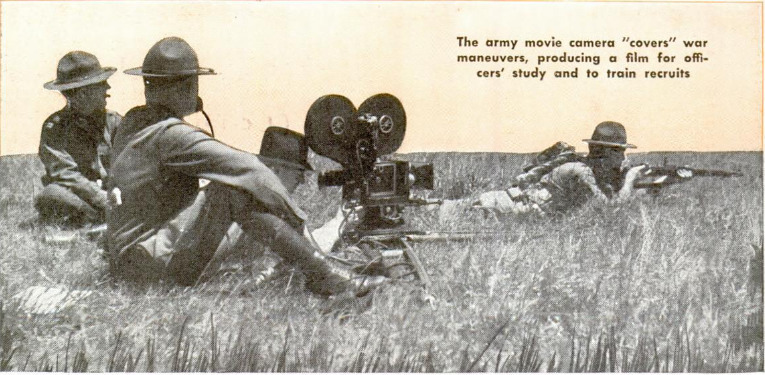

THOUSANDS of feet above the “enemy” lines a U. S. Army “blitz” photographer trips a shutter, thrusts the film into a little black bag and in less than five minutes a finished print showing a concentration of hostile forces is plunging to field headquarters in a metal tube. Three-dimensional films detect the ground swell of a patch of pillboxes that is flat and barren in the “one-eye” photograph, and the color camera discerns camouflage that blends in unnoticed patchwork on the black and white print. The army sees with thousands of glass eyes. Yesterday’s amateur snapshooters have been training as Signal Corps photographers at Fort Monmouth, N. J., or air force cameramen at Lowry Field near Denver. Movie men waist-deep in water grind away as army engineers bridge a stream. They go to Hollywood to learn technique for producing training films, and graduates of the Disney Studios are loaned to the army to “animate” slide films that teach aerial navigation or gunnery or military traffic control. Just recently the army acquired a large motion picture plant in New York City and is transferring the Fort Monmouth film laboratory to this new photographic base. Your Uncle Sam's army has always been right up among 'em in the business of war photography. The Signal Corps is custodian of a priceless pictorial record, of the Civil War and the World War. The Army was the first institution in this country - probably anywhere - to use motion pictures for mass instruction. In the last year of the World War 60 movies were produced for army training purposes. Today there are many more training films in production, the Signal Corps is pioneering in the use of sound films, and the techniques of army caeramen in ’18 are as out- moded as the soundless “flickers” of that day’s dime shows. Troops being schooled for war sit in a lecture hall and watch a battle develop on a screen. A bomb explodes, and the sound of the blast bursts through the room with frightful realism, the purpose being to accustom soldiers to the din of battle. Tank crews see a projectile strike a medium tank and hear the detonation of the hit as recorded from inside the tank. Two tanks crash together in synchronous sight and sound. The peculiar whine of machinegun bursts ricocheting from gravel accompanies a vivid attack scene. “Blitz photography” is one of the specialties at Wright Field, Dayton. Long-range artillery may be firing at an enemy concentration beyond eye range, or “panzer” units may be preparing a surprise attack on the U.S. Army’s flank. The commanding general needs immediate accurate information. An observation plane gets the order by radio to obtain quick photographs. Already “upstairs,” the observer trains his Big Bertha camera on the terrain. He needn’t focus the 20-inch telephone lens; the plane is high up, and the focus is fixed at infinity. He has only to figure the exposure time and lens opening. The shutter snaps, and instantly the film holder is pulled from the camera and immersed in the first compartment of a compact four-bin processing tank. He doesn't have to see what he is doing. He pulls the slide up out of the holder and uses it to agitate the holder in the tank, where the negative is developed for one minute. Then he replaces the slide and moves the holder to compartment two for a 15-second “stop bath.” In the third tank the negative gets 75 seconds in a fixing solution, then a five-second water rinse in the fourth section. Each section of this tank has a nonspill lid so that its chemicals are immune to the bouncing and banking of the plane, and its insulating jacket, 15 inch thick, is electrically heated to a constant temperature of 75 degrees. Development has taken 2 minutes and 35 seconds. Sponged off with a rubber squeegee, the negative in another half minute is ready for the next stop - an efficient little printer packed in a light-proof zipper bag. Here again the aerial photographer works by the touch system, seeing nothing. Thrusting his hands inside the black bag, he lays the negative on the printer and covers it with a sheet of trans- parent material to keep the printing paper dry. Sensitized paper is then placed over the film and the lid is brought down, making the exposure with light from a single bulb. After five or ten seconds in the printer, the paper gets the quick 1-2-3-4 routine of 20 seconds in the developer, 20 in the stop bath, 15 seconds of fixing and a five-second rinse. Drying is skipped; the wax-treated paper sheds moisture, and the print is immediately thrust into a light metal cylinder with sponge-rubber shock absorbers and dropped to the ground. A waiting motoreyclist or jeep car courier rushes it to the field commander. Working time from shutter click to metal tube is only four minutes and fifteen seconds. Never satisfied, the Wright Field researchers under Lt. Col. George W. Goddard are working on techniques that may slice time even thinner. One employs the portrait-while-you-wait method of the amusement-park photographer. Here the negative is omitted, the picture being taken directly on paper. Thus far this process has proved inefficient because of the limited sensitivity of emulsions; only in most favorable daylight can a sharp print on paper be captured by the direct-positive system. But the army is trying for paper with a wider exposure range. Another blitz photography technique utilizes a portable field darkroom developed by Lt. Col. Goddard. Attached to division headquarters, it weighs 50 pounds fully equipped. and can be set o up in less than five minutes. The darkroom is a camouflaged tent five feet square, supported by four pneumatic arches inflat- able by hand pump, air flask or from the spare tire of the jeep. It has a lightproof black fabric lining, rubberized floor that is both waterproof and acid-resistant, and zipper door flaps. A rubber tank holds water for processing, and a small air-conditioning unit provides hot or cold air at the right temperature, whether it’s Alaska or the Panama Canal zone. In the world war, photographs were flown to laboratories 30 miles back of the lines and it took hours to deliver prints to field headquarters. Today’s blitz photographers can deliver a photograph of an enemy mobile battery before it can move its position. There are more tricks in the repertoire of the Wright Field technicians. They consigned to limbo the test pilot’s knee pad on which he scribbled performance notes while jockeying an experimental ship through rolls and dives; to replace the knee pad they built a “Photographic Observer,” a 35-millimeter motion picture camera, a lamp house to provide lighting, and a mount carrying instruments duplicating those on the cockpit panel. At the touch of a trigger switch on the pilot’s stick he can record on film the readings from as many as 15 instruments. To record accurately the take-off, flight and landing performances of planes under test at Wright Field, a gun camera using 35-millimeter strip film snaps three pictures per second as it follows the plane from a portable camera shack opposite the midline of the field. A stop watch is included in the camera’s view so that the pictures constitute a precise time-distance record of the | plane’s trial. One of the newest tools of the military cameraman is a three-dimensional film invented by Douglas Winnek of Mt Vernon, N.Y. Unlike the stereoscopic pictures which ire two images taken by twin lenses at eye distance apart, the new Trivision film needs but one exposure. Ordinary black and white film, color or X-ray film can be used. Winnek softens the back of the film, then impresses on the back (not the emulsion side) an optical screen consisting of minute grooves, about 200 to the inch. The “lenticulated” film is loaded into the camera, its grooved back toward the subject. The image “filtered” through this optical screen for has depth when viewed as a transparency through the back. From the emulsion side the three-dimension effect is lost. The Trivision film has been used at a Navy hospital to make three-dimension X-ray photographs of patients. With it the surgeon can gauge precisely the position of a foreign object in the body. With it the air corps photographer might show the depth of a valley, the height of a bridge or fortress. The third dimension cannot, of course, be translated to paper; but to the amateur viewing a Trivision film it appears almost alive, certainly alive with intriguing possibilities for both military and civil use. In the Signal Corps photography school, rookie cameramen learn the technique of operating cameras, the chemistry of the profession, mounting prints, even the choosing of photogenic subjects. In the training film laboratory the men are divided into groups of scenario writers, animators, film editors and cameramen; each receives highly specialized training in his line. Graduates are finally assigned to photographic companies throughout the army. Some are sent to “cover” maneuvers, although training films generally require special arrangements on location, with close attention to details. If engineers are to learn bridging operations from the film, if gunners are to learn correct firing practice and tank crews the tactics of the “heavies,” the demonstration on the screen must be perfect. Some subjects lend themselves especially well to animated drawings: thus the interior action and recoil mechanism of an artillery piece can be dramatized, or the invisible chain of events inside a vacuum tube can be given life, or a plan of battle can be pictured on an animated map. Slow motion, too, can be employed to teach an efficient march step, the scaling of obstacles, traffic flow or proper handling of arms. The night has a thousand eyes, and some of them belong to the Air Forces. Flying photographers at Lowry Field are trained to use high-speed and high-altitude cameras, bomb spotters, infrared and telephoto cameras, color and reconnaissance cameras, and the new technique of night shots from the air by the light of flare bombs synchronized with the shutter. Signal Corps photographers have been moving in a steady flow from Fort Monmouth’s school to assignments throughout the army. Whether it’s a pictorial history of War in the 'Forties that Uncle Sam wants, or a quick range on an enemy gun emplacement, or a sound movie to train aviation mechanics or tank crews, an army armed with lenses is ready.

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 5, 1942

Popular Mechanics, vol. 77, n. 5, 1942