-

Titolo

-

Training the Glider Army

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Training the Glider Army

-

extracted text

-

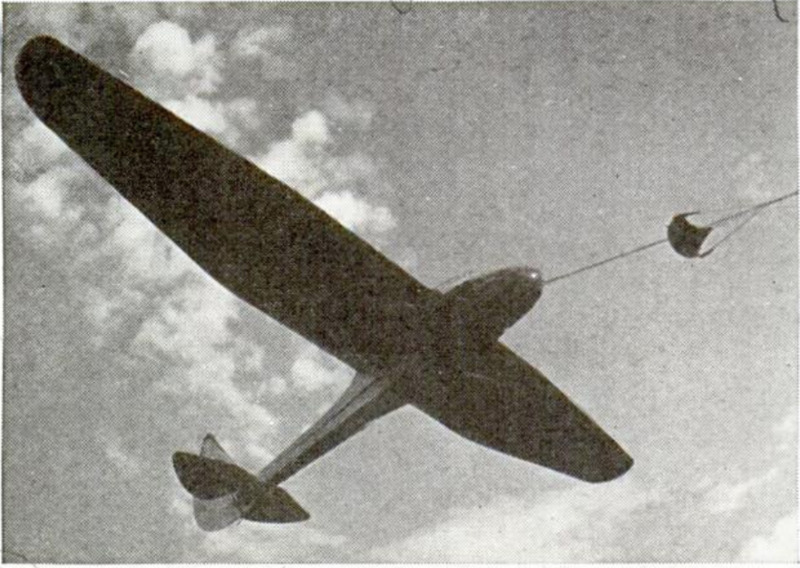

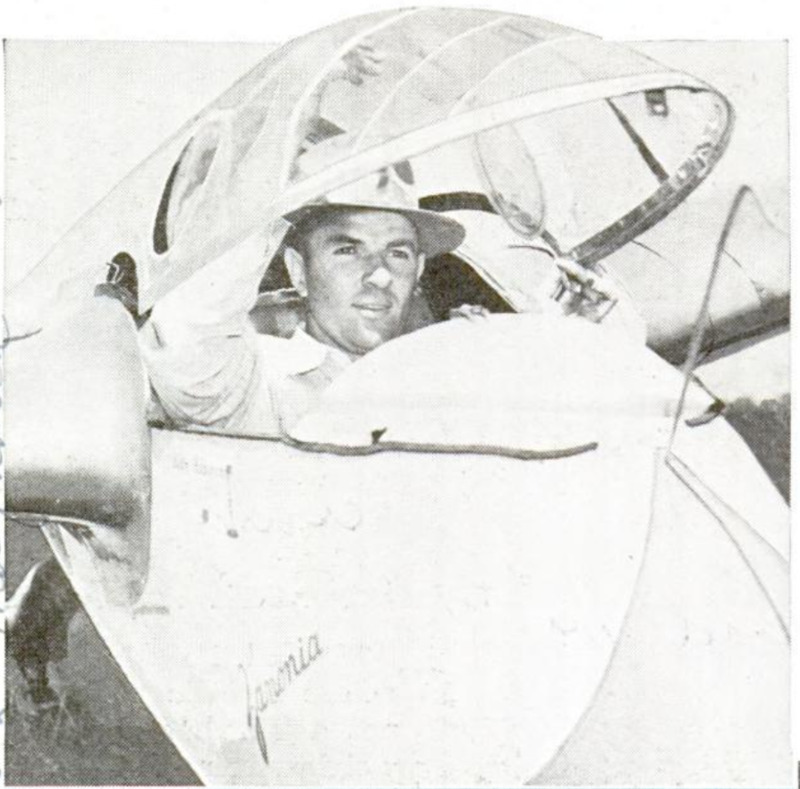

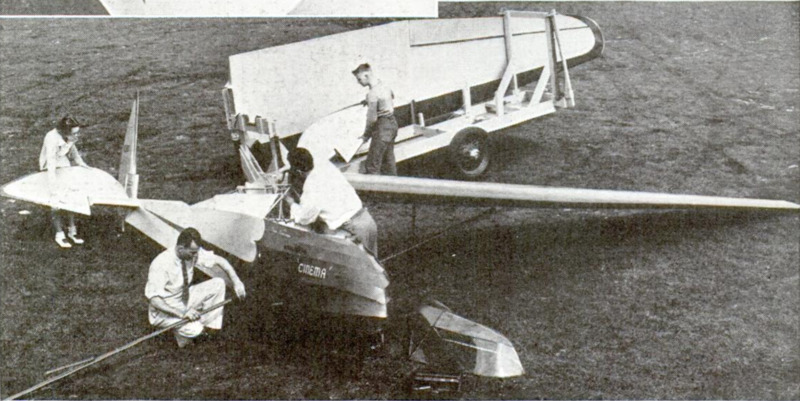

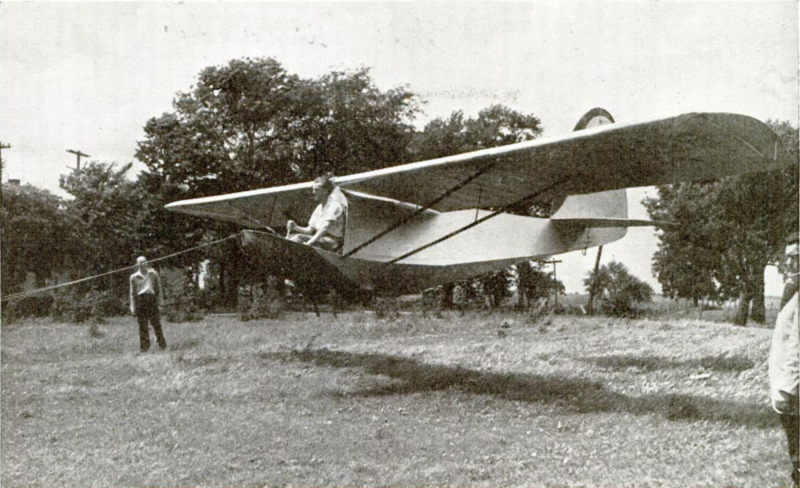

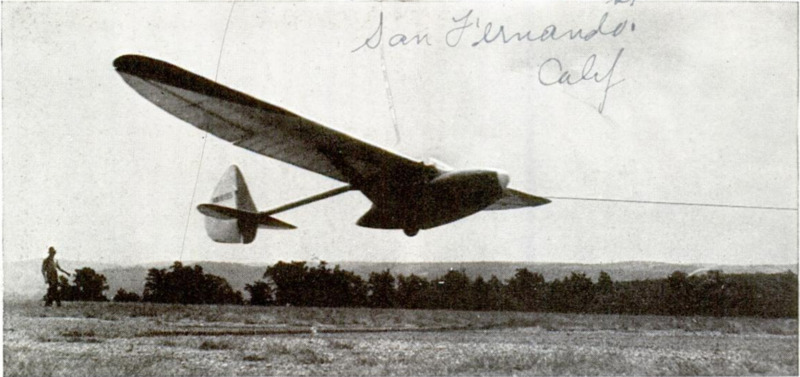

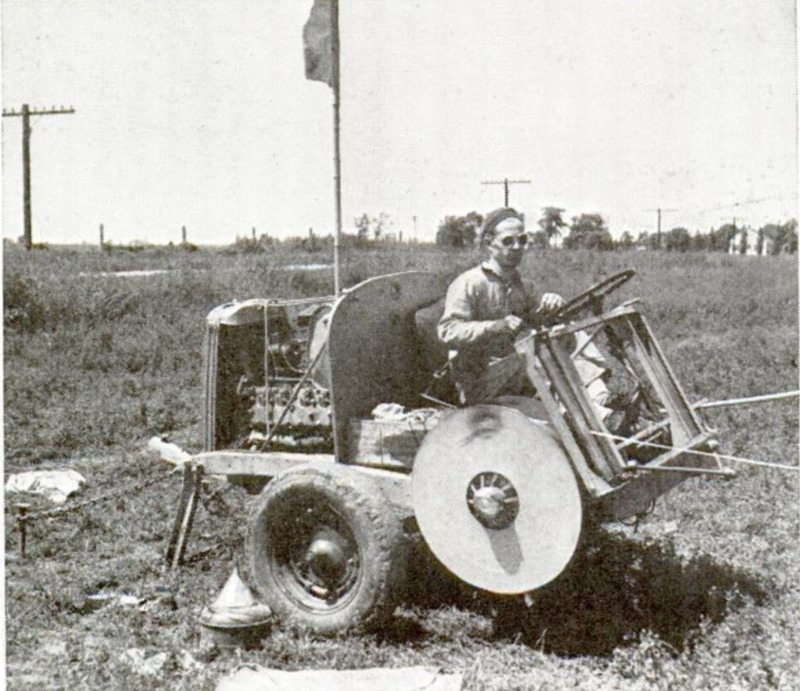

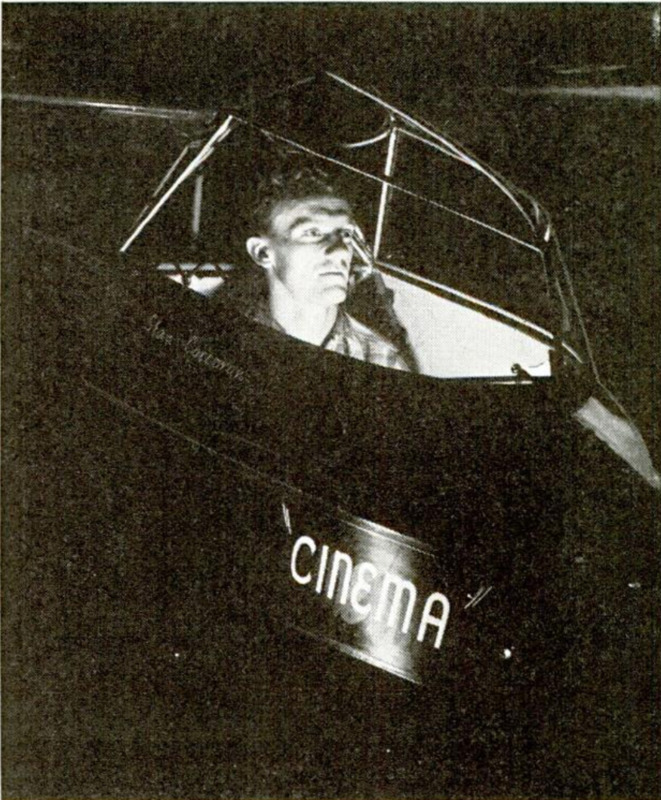

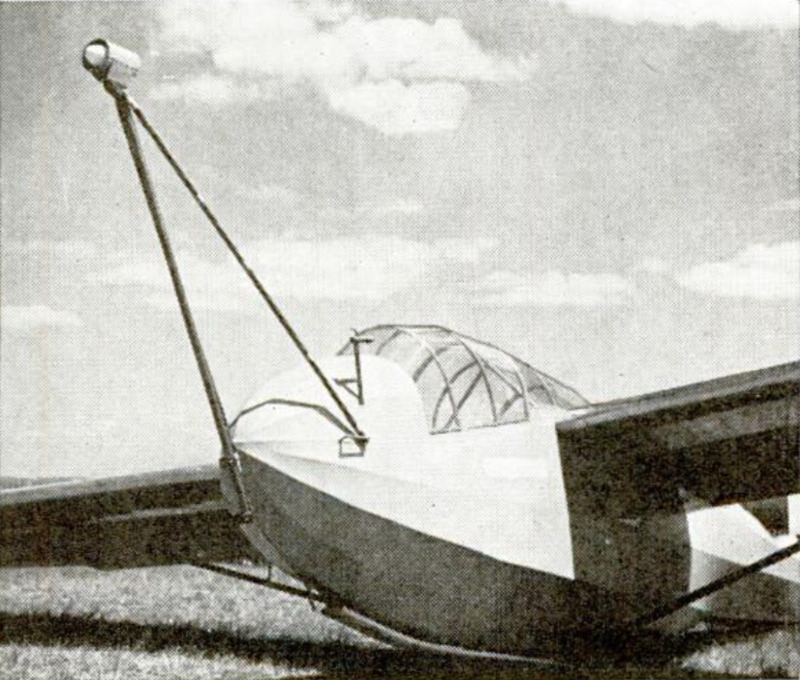

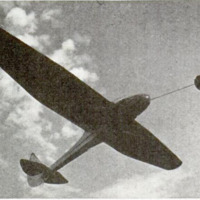

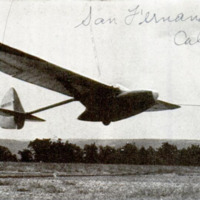

GLIDERS are apt to play an increasingly importhht part in the military establishment of the United States, as a means of quickly transporting large bodies of troops and perhaps small tanks. The Germans demonstrated at Crete the troop-carrying ability of gliders. “Trains” of sailplanes, towed behind airplanes, cast off from the towing planes at a great height and coasted many miles ahead to their objectives. Each glider, according to reports, held about eight fully armed soldiers, including the pilot, and each had separate mobility from the moment it cut loose from the train to make a landing. Sailplanes are used most advantageously where the fighting is over an area so large that troops may be landed from them out of range of enemy fire. Even though an occasional glider crashes on landing, its low cost - a slight fraction of that of a power plane - makes this type of aircraft a relatively inexpensive item in modern warfare. Last summer two groups of U. S. Army officers, all of them pilots of power planes in the Army Air Forces, took three-week courses in glider and sailplane flying. One group went to the Elmira Area Soaring Corporation’s school at Elmira, N. Y., the other to Frankfort-Lewis School of Soaring at Lockport, I1l. This was our initial step so far as military efforts are concerned, in the glider field. If it were desired to move a force of 100,000 men across the country, it could be done in 36 hours by utilizing about 1,000 transport planes, each towing three gliders of 15-man capacity, at a speed of 100 to 200 miles an hour. They could take full equipment, plus machine guns, light cannon and even light tanks, according to one authority. But the vision of the army is not stopping at 15-man sailplanes, for their size is limited only by the power of the planes towing them, hence fifty-passenger craft are within the realm of probability. Construction of a modern sailplane factory, the entire output of which will be taken by the Army, was started recently at Lockport, I1L, by the Frankfort Sailplane company. The company has been making gliders for civilian use for several years. The course taken by the army officers at the Frankfort-Lewis school was typical of both groups. Each pilot received 30 hours’ training during the three weeks. Two-place training gliders were used for initial instruction, each man making eight flights with an instructor before soloing. The training gliders are certificated by the Civil Aeronautics Authority to withstand a speed of 88 miles an hour when towed by a plane. During the course each army pilot averaged 225 glider landings, and demonstrated his ability to bring his motorless ship down on a designated plot of ground about 25 feet square. Individual flights, sustained solely by air currents, ran from an hour to two hours and twenty minutes. So far as glider records go, the endurance record is German-held, at over 36 hours in the air without a landing, with return to point of departure. Likewise in German possession is the altitude record of 22,434 feet. The Russians, who have long been experimenting in the glider field, hold two records for distance - 465 airline miles, and 212 miles with return to point of departure. American-held records are: Altitude, 17,263 feet, by Robert M. Stanley; airline distance, 290 miles, by John Robinson; duration, 21 hours, 34 minutes, by Lt. William A. Cocke, Jr. Gliding has its thrills and dangers. Maj. Fred R. Dent, Jr., one of the pilots attending the Elmira course, ran into some of them when he took to the air in company with John Robinson, holder of the American distance record, in a two-place glider. After being towed aloft to 4,000 feet, Dent and Robinson cut loose from their tow. They entered a cloud at 3,700 feet, and started sailing on instruments. The variometer showed that they were climbing and they started to spiral. They passed out of the cloud at 8,000 feet, and again started climbing, while the windshield and wing edges began accumulating ice. About this time, with the altimeter reading 9,500 feet, the airspeed indicator ceased functioning. Robinson’s vairometer, in the back seat, was still functioning, and he kept Dent, who was piloting, informed of their rate of climb. At 10,000 feet the altimeter had reached its limit of readings, but the air currents kept pushing them up. Then the bank-and-turn indicator quit - frozen. Ice was everywhere, deposited by precipitation from the cloud at that altitude. Of the instruments on Dent's board, only the compass continued to work. They reached what they believe was about 15,000 feet. By the time they broke out of the cloud they were then in, even the floor inside the sailplane was covered with what looked like snow. With no upward currents now, they began to descend, and as they reached lower and warmer levels the instruments again began to function. They landed successfully in a field - but 100 miles from their destination. Sailplanes are launched by three methods: power-motored winch, which pulls the glider toward it and up in the air by means of a long wire cable winding up on a drum; towing via a moving automobile; and towing by airplane. The winch method utilizes about 2,500 feet of cable, and the glider is able to attain around 800 feet of altitude before casting off. In taking off behind a power plane, the process is simply one of handling the glider so that it does not add to the difficulties of the airplane pilot. The latter starts his run on the ground for the take-off, while the glider pilot maneuvers to keep his craft on or very near the ground until the plane gets into the air, keeping the cable connecting the two fairly taut. As the plane starts to climb, the glider pilot follows it until both are free of the ground. A sailplane towed by an airplane, which is the method visualized for mass transportation of troops by air, must be piloted, just as is the airplane. Piloting skill for the glider operator is essential, in order to relieve the airplane pilot of the excessive manual effort necessary for control of his ship, burdened as it is with the load at the other end of the cable. Moreover, improper flight or position of the towed glider is likely to endanger the towing airplane and cause it to stall, due to its low flying speed on a towing job. From the towplane pilot’s standpoint, the first 1,000 feet of climb are the most dangerous. During this phase he must maintain as much air speed and as shallow a climb as possible. If he stalls at this low altitude, due to insufficient air speed, he has little chance to recover. But after 1,000 feet he increases his angle of climb, and flies close to the stalling speed, gaining altitude rapidly in this way. All the while the glider pilot must give his tow pilot every cooperation. Air gusts affect the light glider greatly, so its pilot must watch the power plane ahead for advance warning, as the glider hits the same bump right on the heels of the tow plane. The glider pilot, thus forewarned, cushions the action of the bump by nosing up or down, keeping the tow line at as nearly the same tension as possible. The most dangerous place for a sailplane during a climb is down and to the left behind a towplane, where the propeller throws the air it displaces. Here the slipstream and disturbed air create an area of turbulence so great that a sailplane that ventures into it is almost unmanageable. The best place for the sailplane is directly behind and even with the towplane, or slightly to the right and sufficiently high that the tow ship appears slightly behind the horizon. Major General Henry H. Arnold, chief of the Army Air Forces, revealed something of the army’s attitude toward gliding when he stated: “I have heard it said that the United States Army did not wake up to the military possibilities of gliders until after Crete. The facts are that we have been studying gliders and their possibilities for a long time, but it takes a long time to set a large machine in motion.” He said further that gliders “may spell the difference between success and failure” in many military missions. The Navy has ordered sailplanes utilizing a new material, a wood-impregnated plastic, said to possess the advantages of not picking up moisture or fungus growth; of being light, durable, and capable of being worked into any shape, and of having a “long fatigue limit” that enables it to withstand strains, twists, shaking and the like without cracking or chipping. Some of the Navy’s gliders will carry 24 men each, some 12 men, and others two men. The larger ones will have a wing spread of 110 feet and gross weight of 12,000 pounds, while the 12-place craft will have a wing spread of 88 feet and weigh 6,500 pounds.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1942-05

-

pagine

-

82-85, 162, 164

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Enrico Saonara