-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

He harnessed a Tornado and developed the modern airplane supercharger

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: He harnessed a Tornado and developed the modern airplane supercharger

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

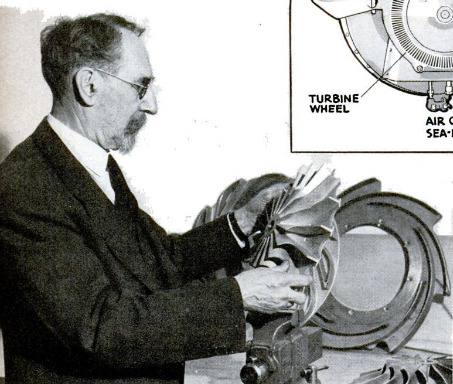

PROBABLY the happiest man in America

today is Dr. Sanford A. Moss, the man

who developed the supercharger, the

device which makes possible the altitude,

speed, and range of the modern airplane.

His greatest creation, the turbo-super-

charger, at last has come into its own, after

twenty years of delay, as a basis for strato-

sphere flying. It has become one of the most

important focal points in America’s sudden

war effort. No effort or expense is being

spared to push its mass production. At last

the sky is really the limit.

‘Twenty-three years ago, in order to help

beat the Kaiser, Dr. Moss harnessed up a

red-hot tornado, sheathed it in heat-resist-

ant metal, and hitched it up to a Liberty

‘motor at McCook Field, Dayton, Ohio. Shel-

tered behind a barricade of sandbags, he

opened the throttle up wide. With a wild

roar of broken connecting rods the airplane

engine disintegrated. The spark plugs tore

out through the roof.

Dr. Moss, a small scientific gentleman

with a Vandyke beard, knew perfectly well

what he was doing in this seemingly irra-

tional behavior, just as any airplane pilot

today knows that you are likely to tear your

engine to pieces if you open up wide at sea

level with a Moss supercharger. He was

giving the turbo-supercharger its first dem-

onstration, and he did his violent deed at the

insistence of a skeptical group of Air Corps

engineers, to convince them that this odd

contraption of his was worthy of an official

test at the top of Pike's Peak, in the rare-

fied atmosphere it was built to conquer. At

half throttle they had refused to be con-

vinced.

On Pike's Peak, in September, 1018, the

turbo-supercharger proved itself. In those

days an airplane engine lost power rapidly

as it gained altitude because, as atmospheric

pressure fell, less oxygen was sucked in to

mix with the fuel in the combustion cham-

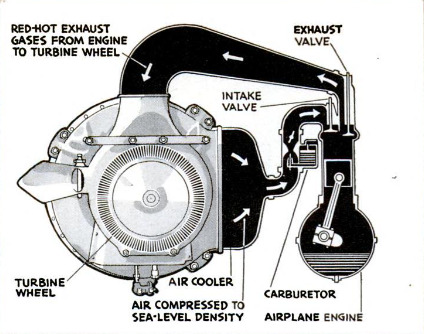

bers. The supercharger was a centrifugal

compressor, or fan, which forced air in sea-

level quantities into the engine's carburetor.

In the words of Dr. Moss, it “kidded the en-

gine into thinking it was at sea level.” The

compressor was revolved by a turbine driven

by a whirlwind of flaming fumes from the

engine's exhaust.

The test Liberty motor, which had pro-

duced 350 horsepower at Dayton, would give

only 230 horsepower at the 14,000-foot alti-

tude of Pike's Peak. But when Dr. Moss

cut in his supercharger, it gave 356 horse-

power. And this full power was much more

valuable than at lower altitudes, for in the

thin, high atmosphere an airplane could

move at high speed with much less air re-

sistance.

One of the great obstacles to flight had

been conquered. Within two years engineers

were bold enough to predict that eventually

airplanes would attain the fabulous speed of

200 miles an hour! Within a few more years

Igor Sikorsky was able to dream, quite

sanely, of 100-ton flying boats crossing the

Atlantic Ocean in less than 20 hours.

And if this country attains its ambition

to produce clouds of airplanes surpassing in

performance any warplanes that Europe

can build, the device which probably will

do more than anything else to make it pos-

sible will be this same turbo-supercharger

—patiently refined and developed, down

through the years, by this same elderly lit

tle scientist-mechanic, who never has been

up in a military airplane, a man so gentle

that he wouldn't put a sleeping dog out of

his favorite easy chair.

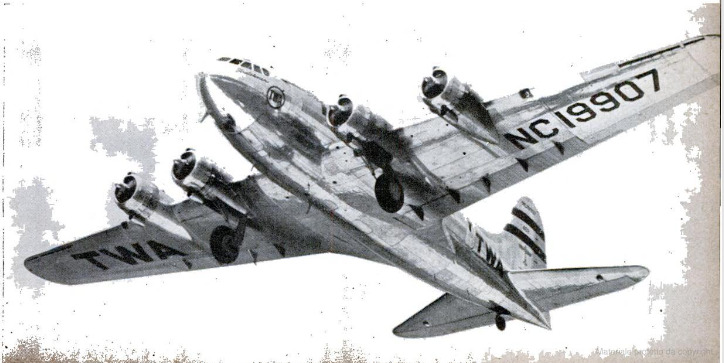

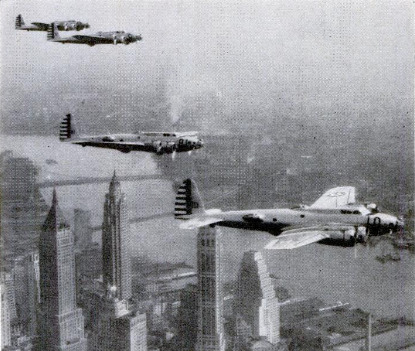

It, for instance, the flying fortress is the

superlatively great airplane that Americans

believe it to be, that is in no small degree

due to the fact that its four engines are

equipped with turbo-superchargers, enabling

it to fly vast distances at great altitude,

with an unprecedented pay load.

In these days of complex industrial en-

gineering, it is rare that any scientific ac-

complishment is so exclusively associated

with one man as is the supercharger with

Dr. Moss. When he retired at the age of 65,

on January 1, 1938, after 35 years of en-

gineering research for the

General Electric Company,

every modern American air-

plane engine (except a few

small pleasure-plane motors)

was equipped with a built-in

geared supercharger that was

patterned after designs made

by Dr. Moss.

Recognized in the industry

as one of the great contribu-

tors to the advance of avia-

tion, Dr. Moss was still a

disappointed man when he

retired. That was because

there are two Kinds of superchargers, both

developed by him, but the one in common

use was not his darling, his great invention,

the red-hot tornado of Pike's Peak.

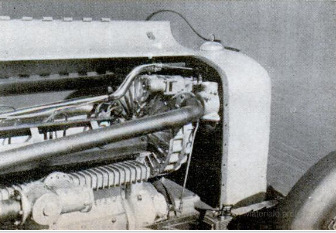

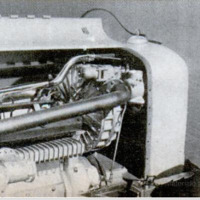

The commercial supercharger is a small

centrifugal compressor built into an air-

plane engine, weighing four pounds or less,

which gets its power by gears from the en-

gine crankshaft. Its gears range to a ratio

as high as 14 to 1, which means that with

an engine speed of 2,000 revolutions per

minute, the impeller is whirling at 28,000

rpm. That is no mean achievement in en-

gineering. This supercharger is of value in

improving the vaporizing of fuel and in n-

creasing power on the take-off, as well us

for its main purpose of maintaining power

at altitude. Lindbergh made his fight across

the Atlantic in 1027 without a supercharger,

but since that time the device has had its

part in every major accomplishment of

aviation,

From 15,000 feet on up, the exhaust-

driven turbo-supercharger takes over, al-

lowing the engine to breathe’ normally up

0 25,000, even 30,000 foot. But the trouble

has been that few people wanted to fiy above

20,000 feet. Satisfactory as it might be for

the engine, it was both uncomfortable and

dangerous for the aviator. Use of the turbo-

supercharger had been limited to a few ex-

perimental ships and to a few squadrons of

the most advanced Army planes. And

though the Alr Corps engineers worked

eagerly with Dr. Moss to develop the turbo-

supercharger, It never seemed to him that

the tactical units made adequate use of its

possibilities.

Tmportant as it was, Dr. Moss's super-

charger department never grew very large.

It occupied one room in the General Electric

research laboratories in West Lynn, Mass.

For years the engineering staff numbered

five men; then, ax business increased, it was

doubled. Alrpiane building simply was not

a mass industry; and when Dr. Moss re-

tired, superchargers were still a dramatic

but tiny part of General Electrics vast

business.

Now suddenly all that is changed. The

little engineering staff has been multiplied

astronomically. The company's best produc-

tion experts have been moved in. Great fac-

tories are being rushed into commission for

mass production of Impellers and turbines

for superchargers. Millions upon millions

of dollars are being poured in.

And back on the Job In the midst of It all

1s Dr. Moss himself, called back to work as

consulting engineer —as happy, dazed, and

excited as two children at the circus. At 68

years of age, his dreams have come true.

The story of the turbo-supercharger is

the story of Dr. Mosw's life, for the device

is the perfect and ultimate expression of his

Whole scientific career. When he was 16

years old he was apprenticed as a mechanic

in San Francisco, In a shop which made air

compressors of the reciprocating type; and

right then began a lifetime of specialization

in the compression of gases and the flow of

gaseous fluids. Afterfinishing his four-year

apprenticeship, young Moss boned up. for

entrance examinations and started as an en-

gineering student at the University of Cali.

fornia, sweeping up the floor of the college

shops to earn his way. By 1000 he had taken

his bachelor's and master's degrees, and

then went on to Cornell University as an

instructor and advanced student. In 1003

he received his degree as a Doctor of Phi-

losophy.

All of Dr. Moss's research work as a grad-

uate student had been on a project for &

gas turbine, which #0 interested General

Electric that he was taken on as a company

engineer to continue the work. This turbine

was to be a primary source of power, com-

bining principles of the Internal-combustion

engine and the steam turbine. One part of

this mechanism was centrifugal compres.

sor, on which patents were first taken out

in 1904. As time went on this compressor

became an important item of company busi-

ness, manufactured for fron foundries, blast

furnaces, pneumatic tubes, oil burners, and

other purposes.

But the gas turbine itself had to be post-

poned. Regrettully It was put away on the

shelf. In a scientific sense no experiment is

a failure If It contributes to human knowl.

edge, but it must have been u terrific disap-

pointment to n practical inventor like Moss

to put aside his great life project.

So matters rested at the time of the first

World War. In fighting planes, altitude is

one of the greatest advantages, and the idea

for a supercharger occurred in various

places at once. The British tried to develop

a geared compressor. The French scientist

Rateau had the iden of driving & super-

charger with exhaust gases. The idea was

all right, but the superchargers wouldn't

work.

After the United States entered the war,

the National Advisory Committee for Aero-

‘nautics took up this problem, and knowing

of Dr. Moss's work, turned the Job over to

him. Tt was right down his alley. His cen-

trifugal compressor was just the thing. As

for power, down off the'shelf came the aban-

doned gas turbine. Within a few months

the two had been hitched up, in the tame

tornado of the Pike's Peak test.

Except for refinements that have been

made through the years, that first super-

charger was the turbo-supercharger of to-

day. Its idea was simplicity itself. The

compressor sent alr into the intake mani-

fold at sea-level pressure. The gases in the

exhaust manifold were also at sea-level

‘pressure, and were directed through nozzles

on the buckets of the revolving turbine.

Technical discussions of the turbo-super-

charger are discouraged in these days of

‘military secrecy; but the difficulties are eas-

lly apparent to anybody who has ever had

trouble with an overheated bearing. The ex-

haust fumes are at 1.500 degrees F. Mani.

folds and buckets are red hot, while the tur-

bine revolves at 20,000 or more revolutions a

minute. And on the same drive shaft, only a

fow inches away, the compressor is handling

‘atmosphere which has been recorded as low

a8 76 degrees below zero! The turbine emits

= four-oot tongue of flume, which at high

altitudes freezes instantaneously, and on oc-

casion has settled as ice on the wings of the

airplane itself,

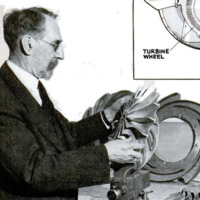

A turbine bucket is a little fin like a blade

on a windmill In the Moss turbine the

buckets are a fringe of little blades, of a

secret heat-resistant steel, mortised into the

rim of the turbine wheel. Tested at 22,000

revolutions a minute, a turbine bucket is

traveling 1,000 feet per second, in a circle

less than 12 inches in dlameter. Weighing

less than 1/100 of a pound, a little red-hot

bucket at this speed is subjected to a cen-

trifugal pull of about 1,750 pounds.

Moss's first turbo-supercharger was light

enough for one man to carry. It was fig-

ured that a commercial compressor deliver-

ing the sume amount of air would weigh

5,000 pounds and occupy a space of more

than elght cubic yards.

‘Experimental work with the supercharger

was interrupted by the Armistice of 1018.

The time was yet to come when it would be

tested in an airplane. Pilots looked at it

dublously. One of them described it as a

combination cook stove, blacksmith forge,

and flying junk shop. An airplane engine

itself 1s a sufficiently torriying bit of

leashed power. A red-hot turbine, revolving

at 20,000 rp.m., was hardly a comfortable

‘companion in the crates which aviators flew

in those days.

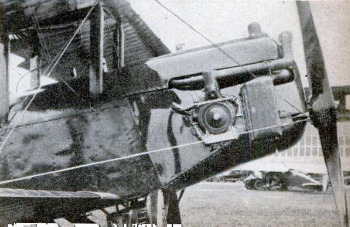

On September 27, 1020, Major R. W.

Schroeder took off in a biplane fitted with

Dr. Moss's turbo-supercharger. At 25,000

feet he encountered a head wind so strong.

that he drifted backward. But he went on.

up and up, until his instruments recorded

33,000 feat. At this altitude his goggles

frosted over. As he struggled with them hls

oxygen supply gave out. Unconscious, he

dived for nearly six miles.

Schroeder never did understand how he

got that plane back on the ground. Half

recovering his consciousness at a few thou-

sand feet altitude, he managed to right the

plane. He could hardly open his eyes. But

Somehow he managed to land safely.

As Dr. Moss improved the supercharger,

allitude records were broken gain and

again, establishing the pioneering fame of

the Army aviators Macready, Stevens,

Street. But the difficulties encountered by.

Schroader have never been really conquered.

Only recently the Mayo Clinic, after re-

searches on the subject, announced that a

man deprived of oxygen at 35,000 feet would

die almost Instantly. Even with an oxygen

mask, at that altitude and low pressure, a

‘man does not function normally. Army fiy-

ers in pursuit ships are under orders 0 use

their oxygen tubes when above 10,000 feet.

In the years just preceding the present

war, there were encouraging experiments

With planes built with sealed cabins, within

‘which warm alr was kept at pressure. But

such cabins are not punctureproof and will

be less useful in war than in peace. Provi-

sion of adequate oxygen for high fiyers is

one of the major problems of the present

Miraculous as the advance of aviation has

been, the slow development of stratosphere

fying has of course been discouraging to

Dr. Moss. That it has developed at all has

been due largely to an irrepressible, impish

quality of the inventor, who for 20 years

encountered what ho called the “glassy eye”

of industrial executives and Army brass-

hats, and would not accept discouragement.

AL the time of his retirement an anony-

mous writer in “Mechanical Engineering,"

who must have known him very well, de-

scribed him thus:

“Painstaking, nervous, his eyes sparkling

with fun or fury, Dr. Mos raises his pointed

beard in his companion's face and looks at

him through the lower lenses of his glasses.

His tongue, trying to keep up with an agile

mind, iv ready for a persistent barrage of

embarrassing questions or a volley of ex-

planations. Ho possesses that disarming

characteristic of small boys with whom it is

impossible to be angry for long in spite of

‘Sometimes exasperating behavior. Once you

have met him you never forget him, but

think of Bim in terms of warm affection.”

Back in the days when General Billy

Mitchell was unsuccessfully fighting the in-

ertia of Army commanders, Dr. Moss was

carrying on his own private war against

the same thing. They couldn get rid of

him, yet they couldn't get mad.

He'ls a man of many engaging idiosyn-

crasies, and his friends have an apparently

inexhaustible supply of anecdotes about

him. He always carries a pocketful of quar-

ters, and engages every one possible in a

coin-matching contest, explaining that this

is not gambling because the laws of prob-

ability will certainly bring him out even at

the end of the year. While enjoying a short

vacation at a summer camp with some of

his associates from General Electric, he was

voted the “best sport.” That was after he

bad been assigned, as his share of camp

work, to be valet to a team of mules. He

turned up for work equipped with an ash

can, a freshly laundered white-wing suit,

and a high siik bat.

He has a habit of asking young men what

their pleasures were as children, and out of

such researches has evolved an aptitude test

which General Electric uses in its personnel

work. His theory is that education should

be concentrated only along the lines of the

pupil's aptitudes. “A young fellow who

never took a clock apart can never become

a mechanical engineer,” he says. He doesn’t

care whether the clock was ever put to-

gether again. What counts is the curiosity

the desire to know how things work.

Once Dr. Moss argued unsuccessfully be-

fore a police-court judge, with elaborate

mathematical formulas, that a speed cop

Could not possibly have clocked him accu-

rately, because the cop had to go faster

than he, to overtake him. More successfully

he once defied a traffic cop who told him to

pull over to the side of the road. “I won't

Go 1!" he exclaimed. “The law says I can't

drive without my license, and you've got It!"

On occasion, t get some place i a hurry,

Dr. Moss reluctantly has flown in & com

mercial airplane; bat he has never been on

an experimental fight. “It would contribute

nothing to the development of the turbo-

supercharger, wo 1 just don't do I” he ex-

Plains. Once his associates at Wright Field

ganged up on him, insisted that he must go

up with them for consultation. He put It

off to next day, and In the morning a tele-

gram arrived from General Eectric, ex.

bressly forbidding Dr. Mow to make the

fight.’ Triumpbantiy he obeyed.

“This reluctance seems to have nothing to

do with courage. No one but a brave man

would fool around with experimental tur.

bines. During the test of the supercharger

at Pike's Peak, bis associates had to tio him

to a post with a piece of rope, while he

worked on the engine, to keep him from ab-

sent-mindedly backing into the whirling

propeller.

Tn all his triumph, Dr. Moss is stl able

to find good-natured cause for complaint,

“First they told me it couldn't be done,” |

he says. “Then they said, ‘What's the good

of it?" And now what do they say? They

say, ‘We were going to do it all

the time." |

Now that the turbo-super-

charger is really being devel-

oped, Dr. Moss is bursting with

ideas of how it could be used for

peacetime purposes. But he still

encounters the “glassy eye.” No- .

body will listen. All they think

about is providing the stuff to

win a war.

Back in the old days he could

complain, argue, make propa-

ganda, fight for his ideas. But

this time he is stumped. The

turbo-supercharger is now so

important that they won't let

him say a word about its pres-

ent or its future.

Even his dreams are military

secrets.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

67-71

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domains

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 6, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 6, 1941