-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Submarines in war

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Submarines in war

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

JUST what is a submarine? It is a war-

ship designed for traveling under water

and attacking its enemy unobserved

with torpedoes. Its ability to surprise is the

submarine’s most important attribute.

A surface warship, when overtaken or en-

countered by an enemy, must stand and

fight, unless it has sufficient speed to run

away. A submarine need not fight, nor need

it show its heels to an enemy ship. All it

need do is submerge, and the surface enemy

is baffled.

The value of the submarine has not

changed markedly since World War I. It

has been improved, of course. Engines are

more reliable and noiseless, better and

greater-capacity storage batteries are in-

stalled, more rugged motors are fitted. Tor-

pedoes have been improved in accuracy, and

run with greater precision. More scientific

methods of submerging have been achieved

and the many instruments and devices used

in underwater navigation have become more

accurate and reliable. Underwater listening

devices in submarines have been developed

to such an extent that submarines now can

fire their torpedoes using direction finders on

the listening-device principle without show-

ing their periscopes.

Submarines today are even more of a

menace to shipping than they were in World

War I. This is due, almost entirely, to the

relatively fewer antisubmarine vessels avail-

able to combat them. The security of the

commerce of any nation fighting another

with a large submarine fleet is almost in

direct proportion to the number of anti-

submarine vessels that can be pressed into

service. Convoys must funnel into known

ports, and therefore submarines can strike

at them with a minimum of cruising. These

submarines need only take up their stations

where the trade routes converge. The con-

voy system is none too simple to work out

successfully. Merchant ships are of differ-

ent speeds, and the speed of a convoy is that

of the slowest vessel. Faster ships have

been placed in convoys by themselves, but

this increases the number of convoys being

used, and many more warships for escort

are needed. The inexperience of merchant-

marine personnel in maneuvering their ships

in close formation is another difficulty. The

lack of experience in handling ships

causes a spread of vessels in convoy,

permitting a submarine to attack

stragglers that are left without proper

escort. This fault increases enormous.

ly the arduous duties of destroyers.

The submarines most important

function is to intercept a warship or

merchant ship, using first stealth and

then invisibility to arrive at a position

from which to torpedo the target vessel.

That seems simple enough to state,

but its accomplishment is not so easy,

nor is it entirely without risk to the

submarine.

The merchant ship or warship may

be a part of a convoy of many vessels.

There may be a number of antisub-

marine vessels present with the con-

voy, the most effective for the purpose

being the very fast destroyer. The

submarine is under water and there-

fore invisible. When it has arrived at

a position from which its torpedoes can

hardly miss, it fires its missiles. At this

moment, it reveals its presence to all

the vessels of the convoy, and then its

troubles begin.

In the bow of the submarine, and

sometimes also in its stern, are tor-

pedo tubes. When a torpedo is fired

from any of these tubes, with either

a powder charge or compressed air,

there is created a large bubble of gas

or air on the surface of the sea above

the submarine. If an antisubmarine

vessel, say a destroyer, is alert, that

bubble gives information just Where

the submerged vessel is located. Then

the destroyer charges down to the spot and

lays a depth-charge barrage all about the

position of the hidden submarine.

The torpedo or torpedoes—oftentimes two

or even more are fired simultaneously at a

particularly valuable target—are then on

their way towards the victim. They leave a

white wake behind them, caused by the air

bubbles from the exhaust of their speeding

turbines. These wakes can be seen by the

attacked vessel and by the destroyers in

the escort, and depending upon the distance

from which the submarine has fired its

shots, the attacked ship has an opportunity

to maneuver to avoid the torpedoes.

The submarine, after discharging its

death-dealing missiles, has an important de-

fensive role to play to save itself from

destruction. This is to avoid the depth-

charge barrage certain to be laid about it.

When the torpedoes were fired, the sub-

marine was at periscope depth a depth

under water from which it could raise the

telescoping eyepiece of the periscope above

water to observe its target. The first thing

for the submarine to do then is to dive as

quickly as possible. From a depth of about

35 feet, it uses its horizontal rudders to

carry it to as great a depth as its hull will

permit, which is not far from 200 feet, and

at once changes its course radically, while

increasing its underwater speed. This will

carry the submarine out of the danger zone

as rapidly as possible.

A depth charge must explode fairly close

to a submarine in order to wreck it, 50 a

submarine attacked by a destroyer still has

a good chance of escape. Destroyers carry

from 40 to 50 depth charges, and they are

most generous with them. Depth charges

are usually set for detonating at about 100

feet. The depth-charge explosion is & point

and the force of the explosion is mostly up-

wards. Thus a cone of pressure is formed,

its size depending upon the depth at which

the charge explodes. If any part of the

submarine is within this cone of pressure,

the effect on the submarine is serious, caus-

ing extreme pressure on every part of the

hull, and consequent leaks. If the hull of the

submarine is outside the zone of pressure,

the effect is less. But even then, the shock of

the explosion will cause the submarine to be

badly shaken up, putting out lights and leav-

ing the personnel in darkness, causing circuit

breakers to blow, and in general disturbing

the morale of the crew. Depth charges ex-

ploding as far as 200 feet away have been

known to cause the personnel of a sub-

marine to lose their nerve, blow ballast

tanks, and bring their vessel to the surface,

to be sunk by gunfire or captured.

While on the surface a submarine is pro-

pelled by Diesel engines. On the propeller

shafts are large electric motors, used for

power in underwater navigation. Large

storage batteries supply the power to the

motors. These motors can be driven by the

engines as generators to recharge the stor-

age batteries. This recharging can be ac-

complished only while the submarine is on

the surface. Recharging of batteries can

be done also when running on engines on

the surface by what is known as “floating

the batteries on the line.”

"T

HE engines give the submarine a surface |

speed of 13 to 20 knots, depending upon

the type of submarine. The large fleet sub.

‘marines are given a higher speed of about

20 knots in order that they can accompany

the battleships. The high underwater speed

on battery and motors is seldom over ten

knots.

A submarines battery capacity is an im.

portant item for maneuverability submerged

nd also for safety. The battery speed of ten

knots can be maintained for only an hour.

Alter that, a speed of three to four knots

can’ be continued for several hours. When |

the battery capacity has been used up, the

submarine must come to the surface to ro

Charge batteries, Just as an airplane must

land when Its gasoline tanks are empty. |

Modern submarines are capable of remain.

ing submerged for upwards of 24 hours by |

running only at & low submerged speed,

about three knots, until the battery is used |

up. That is the renson why so great a |

proportion of submarines escape from de-

stroyers after having attacked convoys.

Darkness often will intervene before the

battery ls exhausted, and the submarine can

escape on the surface under cover of night. |

‘One of the submarine's limitations ia in

its inability to prevent antisubmarine ves-

sels from tracking it by using their listening |

devices. Listening devices have been greatly |

improved since World War I. In 1018, oven

with Inefficient listening devices fitted In

antisubmarine vessels, the German submar-

ines suffered a breakdown of morale owing |

to the large number sunk by destroyer depth

charges. The British Admiralty gave no re-

ports on submarine sinkings, and the Ger-

mans only knew that submarines never |

returned to their bases.

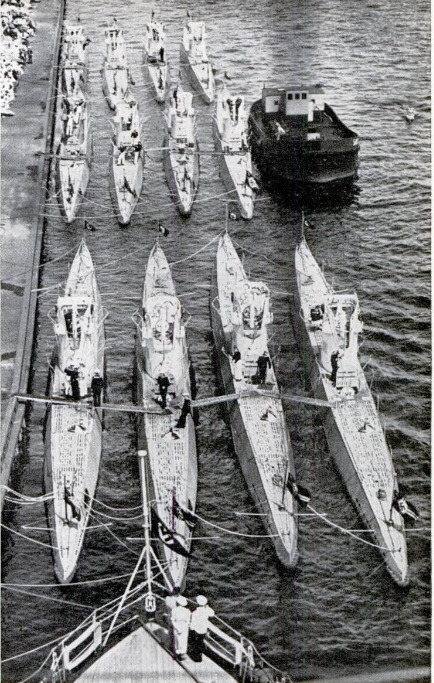

A convoy is usually formed in columns of

‘vessels, with the leaders In line. The distance

between snips is maintained as close as the |

experience of the personnel seems to war-

rant, bearing in mind that danger from

collision is as great a risk as even submarine

attack.

‘The escort is placed on the outside of the

columns. The destroyers or other antisub-

‘marine vessels are stationed close in where

they can turn quickly and steam to the loca-

tion of the attacking submarine. Cruisers

and even battleships and airplane carriers

are located far out on the flanks of a convoy,

to shield the mass of merchant ships from

the gunfire of an attacking surface raider.

The submarine may be informed of the

Tocation of a convoy by patrol planes while

yet the convoy is out of sight. Then the

submarine will use its engines on the surface

to place itself in the path of the convoy.

Before being discovered by the escort, the

submarine submerges and runs on its bat-

tery and motors. During this latter time the

submarine will be at periscope depth, or

about 35 feet, and uses its periscope obser-

vations to correct its position relative to the

selected target. When a correct position is

reached, within short range of its Intended

victim, the submarine will fir its torpedoes,

using its periscope for accurate aim, or else

fire the torpedoes while completely sub-

merged, employing the listening device to

give the angles of sight for the torpedoes.

The submarine can carry only a limited

number of torpedoes, so It will attempt to

reach a distance from which a miss 18 im.

possible, although the torpedo will run ac-

curately for a distance of 3,000 yards or

more, The ideal position for firing 1s within

1,000 yards of the enemy vessel. Such a

maneuver makes the submarine’s part a

most hazardous one.

Long-distance planes often serve as the

eyes for a submarine fleet. Communication

between the underwater vessels and the

‘planes is by radio. A submarine can use its

radio while submerged to communicate with

other submarines and with airplanes. Be-

tween submarines, communication by radio

is practical up to 100 miles. On the surface,

the radio equipment of a submarine is equal

in performance to that of a surface warship.

THE airplane bomber has proved most

effective against submarines. Oftentimes

the submarine can be surprised while on the

surface and bombed before it can submerge.

Bulletproof armor is carried on the exposed

parts of a submarine’s hull, but otherwise

the hull is most vulnerable to shellfire. A

surface vessel can receive a number of shell

hits on its hull without seriously impairing

its seaworthiness, but not so with the sub-

marine. One shell hit, and the submarine

will be unable to submerge.

The personnel of submarines must all be

men of experience. They are usually of the

petty officer's rating, es-

pecially trained for the

duty. In the U. 8. Navy

a submarine school 1s

‘maintained to train off

cers and men for this ex-

acting service. Crews are

usually made up from

volunteers aelected for

courage, who can stand

the enormous strain of

submarine duty without

loss of morale. Few men

in’ submarines are over

35 yearn old, and mot of

them are much younger.

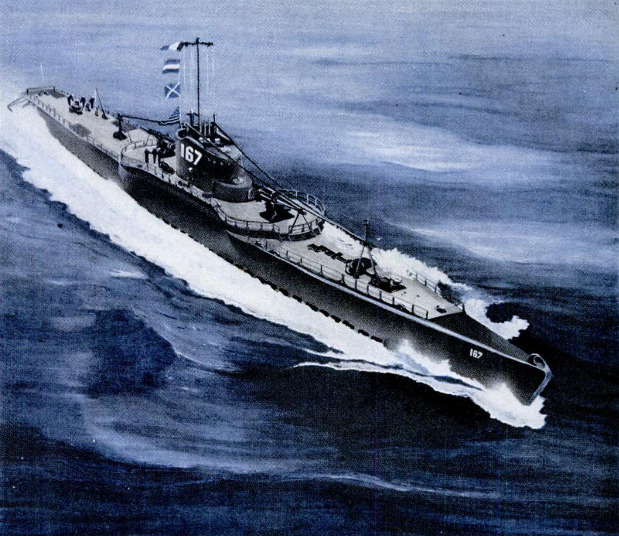

The modern United

‘States submerine ina ves-

sel of about 1,400 tons

surface displacement. Its

principal characteristics

are habitabllity, long

crulsing radius, high sur-

face speed (20 knots) and

submerged speed (10

knots for one hour), and

the ability to remain 24

hours under water at

three knots speed before

the batteries are

completely discharged.

Torpedo rooms are large

enough to carry from 15

£0 20 torpedoes. The sub-

‘marine is given most ef.

ficient ventilation, and

the means of extracting

impurities from the air

and supplying oxygen de-

ficiencies, when sub.

merged,

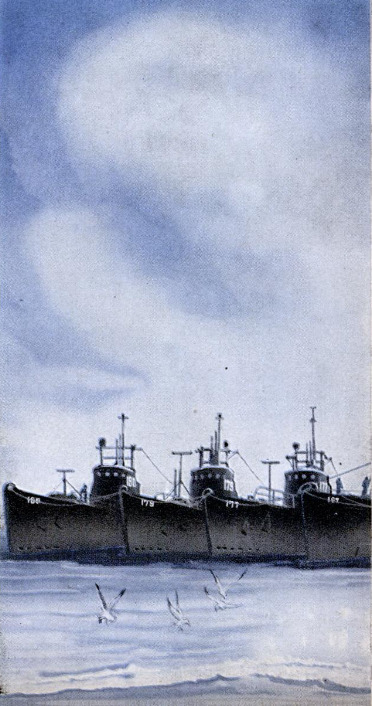

The role of our United

States submarines in war

is to take the offensive

off the coast of an enemy.

They are a mazimums-

purpose vessel, and can

operate both against the

enemy's lines of com-

munication at consider-

able distance from their base, and likewise

off our own coast line to break an enemy's

blockade.

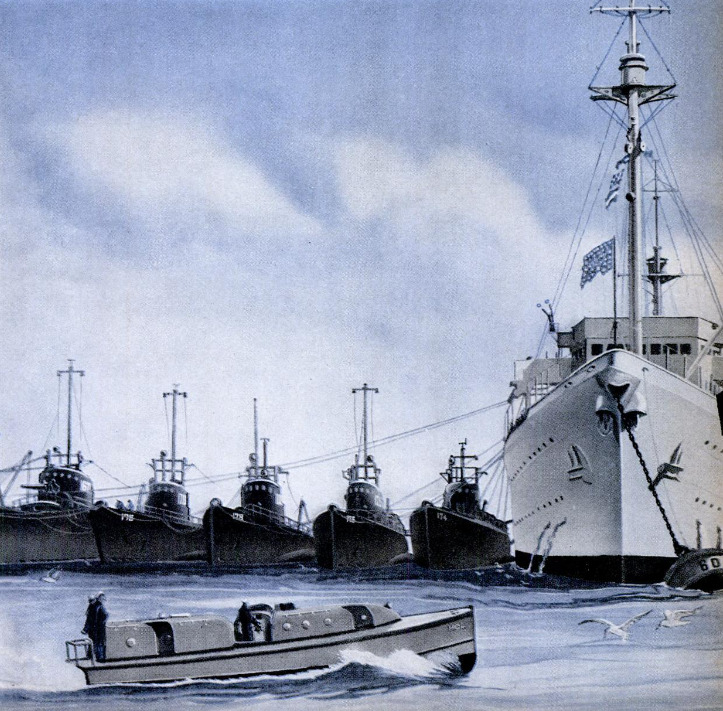

The submarine is said to be the weapon of

the weaker sea power. It is relatively inex-

pensive to build, as compared with the large

surface warships. A submarine of the 1,400-

ton type costs about $5,000,000, while a

cruiser costs upwards of $15,000,000 and a

battleship as high as $70,000,000. The sub-

marine is a weapon of great promise, men-

acing warships and merchant ships alike

in all parts of the ocean. In cosperation with

airplanes it can extend its vision for hun-

dreds of miles, and it can operate without

support from any other vessels.

In war the command of the surface of the

sea belongs to the side that owns the most

numerous and formidable fleet of surface

warships. This advantage enables that side

to use the sea with its merchant shipping

and all its warships. The weaker side in

surface warships cannot command the sur-

face of the sea. This is the reason Germany

has used submarines to torpedo every vessel

that sails the sea. Everything that moves

on the surface is considered by the sub-

marine as an enemy.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Yates Stirling (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

81-85

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 6, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 138, n. 6, 1941