-

Titolo

-

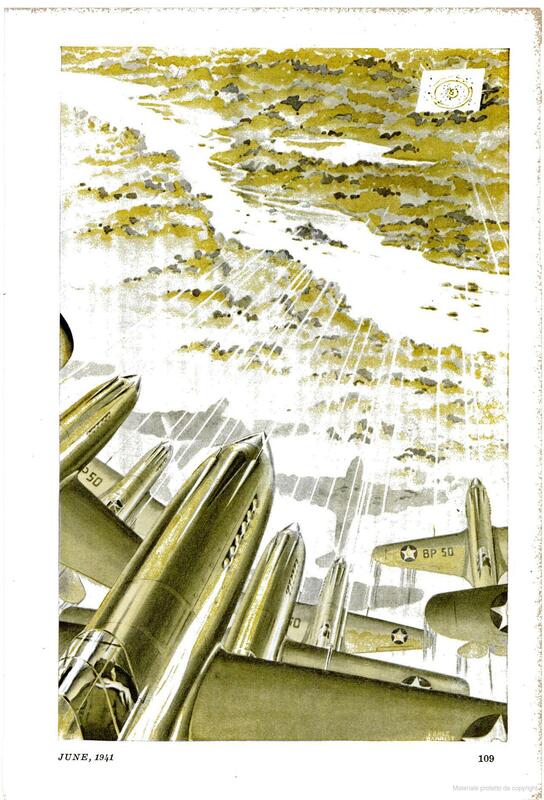

Dog lighting is a pursuit pilot's business

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Dog lighting is a pursuit pilot's business

-

extracted text

-

THIS is an article about dogfighting and

pursuit gunnery, but there is no use

talking about fighter planes and their

tactics without visualizing the kids who fiy

them. A pursuit plane is nothing until it

is fused with the personality of a scrappy,

cocky youngster whose skill is sharpened

and kept to a razor edge. Rush Howard

Willard, from Bay City, Mich. is a good

indication of what is involved when America

tries quickly to set up a strong air force.

Rush Willard is 22. He first had his hands

on an airplane stick at the age of six, when

his legs were too short to reach the rudder

controls. At 16 he was flying solo, and

about that same time he and a friend built

themselves a plane, out of salvage from

several wrecks. The inspectors would not

give them a license, but they hopped it over

a few fences, just to prove it would fly, then

made it into an ice boat

Rush probably would be graduating this

June from engineering school if he had not,

in the fall of 1939, attained his greatest

ambition. He was appointed a flying cadet

in the U. S. Army Air Corps. Out of a batch

of 20 applicants, he was the only one to

pass the physical exam. Out of a primary

training class of 56, he was one of 30 Who

made the grade and won their commissions

at Kelly Field last September, ater nine

months of intensive training.

Now that he had won his wings, Second

Lieutenant Willard still had a great deal

to learn about flying. Assigned to the 33rd

Pursuit Squadron, he spent the next three

months in the exciting process of mastering

a tactical airplane, a fast, powerful, single-

seat Curtiss P-40.

By the time I met him, in late winter, he

was a precision pilot, a good formation

flyer, and in the regular morning rat race

he could throw his plane around with the

best of them. He was now ready to begin

learning to be a fighter.

To most of us, the mere flying of a plane

is an accomplishment far beyond our ex-

pectations. Young Willard was already an

aviator before he enlisted as a cadet, and

that gave him about as much head start

over his classmates as a child has who

learns to read before he goes to school.

Only by a few flying hours, for instance,

did he have any advantage over the other

99 percent of cadets—like his roommate,

Lieutenant Max McNeil, from Raymond,

Wash., who had been in a plane only once

before he became a cadet.

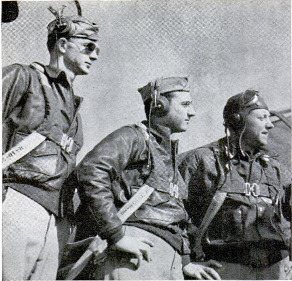

‘Willard was one of the youngsters break-

ing in as a pursuit flyer at Mitchel Field,

Long Island, under the tutelage of Lieuten-

ant Phil Cochran, of whom I told last

month. While I waited for a chance to talk

more with Cochran, I sat around getting

acquainted with the kids.

“You know, it was POPULAR SCIENCE that

got me started in this,” said Max, when [

told why I was asking so many questions.

“I read an article on Army flying, which

got me all excited. I was a sophomore at

Washington State College in 1939 when the

flying board came around giving exams,

and I remembered that article and joined |

up.”

“That's funny,” said Rush. “I read that |

same article, and after that there wasn't |

anything I cared about but getting in the |

Air Corps. I took a physical exam every |

six months to be sure I'd be able to pass.” |

Rush went two years to Bay City Junior |

College, to qualify for the Air Corps mental |

standards. He earned his way by leading |

a 12-piece dance band.

Phil Cochran looked out of his cockpit

at Rush Willard, who was close beside him

in echelon right. Phil held up his right

fist, shook it beside the glass pane of the

canopy. Rush held up his left fist and shook

it back. A challenge had been accepted.

The pair cut out of formation and swung

off where there was plenty of room. They

separated, then drove at each other head

on, at top speed, passing close. At the in-

stant of passing, the fight was on. Now

it was a question which could turn the

quickest, without losing speed.

Back in the World War days, flyers lived

in an age of invention. The man who could

discover a new trick became an ace, be-

cause he took his opponents by surprise.

Nowadays it is about as easy to invent

some new way of throwing a plane around

as it would be for Joe Louis to produce a

blow. brand-new to boxing. The pursuit

fiyer has to learn all the tricks, as part of

his elementary knowledge. But he depends

on his turn, as a fighter depends on his left.

A pursuit plane fires only in the direction

in which it flies. The fiyer does not aim his

guns, he aims his plane. Also, it is virtually

impossible to shoot down a fighter plane

from the side, because it is moving too

fast. Therefore the dogfighter has two ob-

jectives: to get on the tail of his opponent,

and to keep the opponent off his own tail.

Only from the tail can he get a good shot.

The quick turn is the means of accomplish-

ing both these ends. That is what they

mean By maneuverabliily,

A plane built primarily

for speed has small wings,

a high wing load. In turn

ing, banked vertically

against centrifugal force,

such a plane will “mush,”

as an automobile skids; and

this slows up its turns. That

is one reason the British

planes, with lower wing

load, have done so well

against the fast Messer-

schmitts. In a close turn, a

Messerschmitt stalls.

There has been some con-

troversy about the relative qualities of

American and European fighter planes; it

has been said that the Messerschmitts can

run away from anything America produces.

I didn’t discuss this with Phil Cochran, and

certainly he wouldn't want to get mixed up

in any controversy. But it is interesting to

consider his fighting philosophy, which he

is imparting to the youngsters.

Phil doesn’t figure he is going to want to.

run away, or that his opponent will want to,

cither. He will be trying to get at a bomber,

while his opponent will be trying to protect

the bomber, and the two of them will stay

right there and fight it out. In such a

finish fight he wants to be able to excel in

the turns.

“The guy that can turn inside the other

will win,” he tells the kids. So they prac-

tice turns, drawing them tighter and tighter,

fighting against each other. If the turn is

too tight, then the plane stalls—that is, it

loses speed and starts to fall. The idea is

to pull the turn up just to the point of

maximum effectiveness. And of course, in

any turn worthy of the name, the fiyer

blacks out; centrifugal force drives the

blood from his head and he goes uncon-

scious for an instant. He has to go on flying

his turn precisely, while semiconscious. It

takes not only skill, but constant practice.

Chasing tails this way, one plane often

wants to duck away. A dive is bad, for

though speedy it loses altitude, the fighter's

great advantage. One helpful trick is to

dodge into a cloud. The unwary pursuer

will follow, but the wise one will climb

above the cloud and wait for his quarry to

reappear, then dive on him. Another trick

is to climb straight into the blinding sun,

and thus to lose the plane behind.

Working in all three dimensions, planes

do not merely make horizontal turns. A

pull back on the stick brings the plans up

sharp into the start of a loop, which 18 a

vertical turn. But Phil Cochran tells the

Kids that the loop is a silly maneuver.

Speed is lost, There 1s a good chance the

following plane can turn inside, and in any

case he can probably draw the loop just

as tight, 50 there is nothing to be gained.

“There Is another turn, though, used when

a pursuer is close behind. The pilot draws

himself up close and tense, then shoves the

stick hard forward. The plane noses down

and under. With a terrific jolt, the wing

load reverses. The sudden reverse strain,

of seven or elght gravities, would tear any-

thing but the best plane apart. The fiyer's

safety belt is strained to the utmost. He'd

better have hi neck pulled in, or he will

crack his head on the canopy above it. No

black-out this time, for the blood all rushes

to the head. I is very uncomfortable.

It is especially uncomfortable for the fiyer

following, for he hasn't been expecting it

and hasn't had a chance to get set. It is

embarrassing too, for In doubling under the

leading plane goes into the blind spot under-

neath ita pursuer, and for the time being

cannot be seen.

‘After Phil Cochran told me about this

violent. maneuver, 1 was talking about it

to another flying officer.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “That's one they say

the Measerschmitts use to get away from

Spitfires. The German planes have fuel in-

Sectors, which are not affected by the ro-

versal of gravity. But the Spitfire has a

carburetor, When it reverses, the carbure-

tor float control pulls up, and the engine

dies for a moment.”

Thus the fighter pilot feels for, and uses,

the weaknesses of his adversary.

Fighter planes move so fast that, when a

plane does manage to get on the enemy's

tail, the pilot must fire on the split second.

And he must aim, with microscopic ac-

curacy, at a plane which may be traveling

more than 300 miles per hour. There is no

use for a pilot even to start gunnery prac-

tice until he can fly with the utmost pre-

cision.

Rush Willard and his contemporaries

were ready, this spring, to take the ground

gunnery course—known, from its Army

regulations number, as “Four-forty dash

forty.” For this course the pilot goes to a

gunnery camp and spends three weeks.

Stretched across the range is a row of

six targets, enough for one flight to use at

a time. Fach target is ten feet wide, six

feet high, and is set at an angle of 60 de-

grees on the ground. The bull's-eye is three

feet in diameter, and there are two rings

around it.

After a certain amount of preliminary

work, the gunner starts making his runs

for score. One of his four guns is loaded

with 50 rounds. Diving on his target, his

eye glued to his sight, he must not fire

until he has passed the marker for a range

of 500 feet. Then a light touch on the

trigger, which is on the handle of his stick.

There is time for no more than four or five

shots before he has to pull out of his dive.

He has ten dives in which to fire a run of

50 rounds. Then he lands to reload and

the score is counted up. A hit on the bull's-

eye counts 5, the next circle 4, the next 3,

and a hit on the target outside the circles

is worth two. The possible score is 250.

If a man is really good he will shoot around

230.

To make an official score in “44040,” the

flyer makes two runs at 500 feet, two runs

at 700 feet, and two runs at 1,000 feet,

from right and left-hand approaches.

The good marksman does not merely aim

at the target, he aims for 5, 6, or 7 o'clock

on the bull's-eye. In a cross wind he has to

allow for “crab,” a sideways motion of his

plane. He has to have his wings precisely

level when on the target. The several guns

on the plane are set, of course, to converge

on a small pattern at a selected range.

But when the plane is tilted a variable fac-

tor enters. A bullet does not fly straight;

its trajectory is an arc, vertical to the

earth. The trajectory does not tilt with the

plane. Lift a wing and your

guns are out.

After making his score on the

ground targets, the pilot must

shoot at a moving target. This

is a tow target which is at-

tached to the end of a cable that

extends several hundred feet

behind the bomber that is flying

it. The pilot has four runs of

50 bullets, and each hole in the

sock counts one point. Several

gunners fire on the same sock,

but each has his bullets painted on the tip

with a distinctive color. The bullet which

hits leaves a telltale trace of paint around

its hole.

“There are three ratings for men who have

taken this gunnery course: Expert, Sharp-

shooter, and Marksman. To remain a pur-

suit pilot, a flyer must rate as Expert.

Ground gunnery, of course, is only

an introduction to aviation marks-

manship. The pursuit pilot must fire

at moving objects, and providing a

counterpart for actual combat shoot-

ing has always been a problem. For

a while the Army used camera guns,

but these proved to be inaccurate, for

light travels to a camera faster than

a bullet goes to its objective. Like a

duck hunter, the pursuit pilot always

has to take a lead. Today the British

are using cameras in their planes to

record the effect of combat marks-

manship on strips of motion-picture

film. But for practice something else

had to be found.

One method the Air Corps now uses

is to fly a plane over water in bright

sunlight. The shadow on the water

then becomes the target. Diving on

the moving shadow, the gunner can

determine just how accurate his fire

is, by watching the splashes.

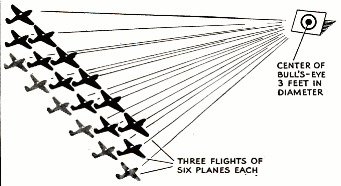

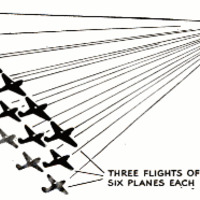

A pursuit squadron is supposed to

have 25 planes, with three extra pilots. But

in the air its strength is 18 planes in three

flights of six, unless the squadron com-

mander chooses to fly separately as a nine-

teenth. Each flight commander's plane has

a stripe marking; each squadron has a

distinctive color for the nose, stripes, and

wheels of its

planes, as well as a distinctive insignia

painted on the planes.

All the while he is perfecting himself in

dogfighting and gunnery, the young pilot

must also be developing as a formation

flyer. He is now able to fly in complicated

tactical maneuvers with his whole squadron.

There is one maneuver which the pur-

suit flyers perform to impress foreign dig-

nitaries, and it demonstrates as well as any-

thing the skill that these squadrons attain.

“Sandwich fire,” as this maneuver is called,

is the concentration of all a squadron's guns

on a single ground target.

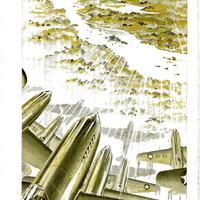

The 18 planes are flying in three flights

of six, each in flight front, one above

another. The squadron commander is at

the left of the top flight. The two flights

below trail a little behind, like steps.

Now the squadron commander tilts his

formation into a dive toward a three-foot

bull's-eye, far below. The steps straighten

out into a solid curtain of gun muzzles

speeding toward the target. As the planes

dive, they are all converging toward a sin-

gle point, drawing closer together.

At 2,000 feet they open fire, with all ma-

chine guns blazing away. At 1,000 feet,

still firing, every one still holding true to the

Dbull's-eye, their wing tips are nearly touch-

ing; the planes of Flight B, the “meat” of

the sandwich, have planes scarcely more

than two feet above them and two feet

below. The pilot in Flight B cannot see the

plane below him, can judge its position only

by the planes on either side. In a split

second more, all converging toward a single

point, they would come together in a tan-

gled mass of wreckage.

At this instant the flight commander

swoops his plane upward, in a left turn;

and simultaneously his flight makes a simi-

lar turn, swinging into string formation.

Immediately behind them, but at a lower

level, Flight B makes the same upward

turn, clearing the way for Flight C to pull

out of its dive. In less time than it takes

to breathe, they are flying off to the left

in normal string formation—echeloned right

just enough to keep out of each other's

prop streams.

Such a living curtain of machine-gun

fire is a horrible thing to contemplate, when

you stop to think about its ultimate pur-

pose. But with kids like Phil Cochran and

Rush Willard you don't think about things

like that. It is fast, thrilling sport. A pur-

suit squadron is like a football team, only

more S0.—HICKMAN POWELL.

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-06

-

pagine

-

106-112,220

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik