-

Titolo

-

Soldier engineers

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Soldier engineers

-

extracted text

-

WHEN the army moves across-country,

the engineers have much to do with

moving it. Their maps have outlined the

route. Their roads carry the motorized forces

and supplies. Their bridges cross the rivers

which otherwise would block the progress of

the army. If rails have had to be laid to the

operating base, the engineers have laid them

and the trains are operated by engineers.

It is the engineers who are indispensable

in establishing bridgeheads in enemy terri-

tory. It is the engineers who plant mines

and tank traps on unprotected flanks. It is

the engineers whose camouflage protects

the artillerv positions and the supplv dumps.

In a pinch, when the enemy attacks in un-

expected force, it is the engineers who throw

down their picks and jack-hammers and

fight with rifles and machine guns.

Engineers always have been an important

factor in the conduct of war, but the ex-

ploits of the combat engineer troops of the

German Army in Poland and the Low Coun-

tries have put new emphasis on their duties.

It was these German pioneer troops, mov-

ing forward in some cases with structural

steel exactly fitted and marked for certain

bridge sites, who established bridgeheads.

It was these pioneers who stormed Eben

Emael, near Liege, and other forts, both in

the Low Countries and in France, which

had been deemed impregnable. Eben Emael,

rated one of the strongest fortifications in

Europe, lasted only seven hours after the

pioneers, backed by aerial bombardment

and parachute troops, got down to work.

Advancing in their own smoke screen, the

pioneers used flame-throwers and thermite

grenades and then thrust through the de-

serted ports long jointed rods, on the ends

of which were charges of explosive much

more destructive thana 75-mm. artillery shell.

U.S. Army engineers, a

large part of whom had been

employed in peaceful years on

flood control, harbor improve-

ments, and supervision of

‘Work Projects Administra-

tion jobs, did not neglect the

study of German methods,

though the German military

engineering policy as a whole

is not regarded as best

adapted to American needs.

The German pioneer forces

regard themselves primarily

as combat troops. The Amer-

ican Army engineers are pri-

marily technicians and the

American Army recruit, al-

most invariably mechanically

inclined to some degree, lends

himself to such use.

On June 30, 1939, the Amer-

ican Army numbered about

180,000 men, of whom 6,000

were engineers—one man in 30. On June

30, 1941, with 1,400,000 men in the Army,

85,000 of them, or one in 16, will be engi-

neers. In active warfare the proportion

probably would rise to one man in eight.

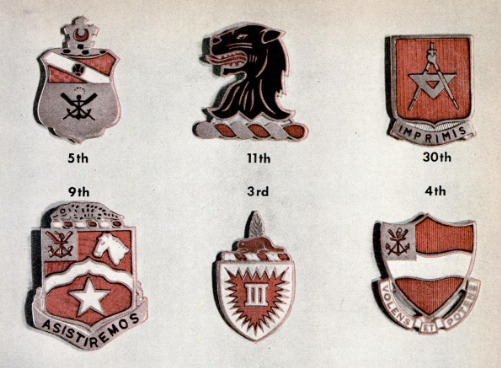

By the end of June each of the “square”

divisions, the major component of which is

four infantry regiments, will have a regi-

ment of engineers. Each “triangular” di-

vision of three infantry regiments

and each armored division will

have a battalion of engineers. Each

cavalry division will have a squad-

ron of engineers. Each army corps

will have one or two combat engi-

neer regiments and a topographic

company. Each field army will have

three regiments and six separate

battalions of general service engi-

neers, two dump-truck companies,

two heavy ponton battalions, four

light ponton companies, a topo-

graphic battalion, a camouflage bat-

talion, a water-supply battal- |

fon, a shop company, and a de-

pot company. Two regiments

of aviation engineers, trained

in construction of flying fields

in war zones, are attached to

General Headquarters Air |

Force, and separate companies

are stationed in Panama,

Puerto Rico, and Alaska.

Experiments are being made

constantly with methods of de-

fense and attack at the Engi-

neer School at Fort Belvoir, Va.

There are courses in technique

and tactics, surveying, draft

ing, map reproduction, water

purification, and heavy me-

chanical equipment. It has be-

come one of the largest special

service schools of the Army,

training 1,700 officers and 1,500

enlisted men annually.

Maintenance of roads and |

bridges and the construction of

new ones probably would be

the principal tasks of the engi-

neers in wartime. Military op-

erations are hard on roads, es-

pecially in this day of mechan-

ized armies. It was far from |

negligible even 25 years ago.

During the six-month battle of

Verdun, trafic over the road

between Verdun and Bar-le-

Duc wore down ten feet of

road metal in the aggregate.

The construction of new |

concrete roads is impractica-

ble close to the front. An 18 |

foot macadam road will meet |

the needs of an infantry divi-

sion fighting as far as 75 miles from its rail-

head. Every infantry division requires one

such road. Dirt, gravel, plank, or corduroy

construction will suffice for lighter traffic.

For quick construction a “tread” road is

built, supplying a bearing surface only for

the wheels.

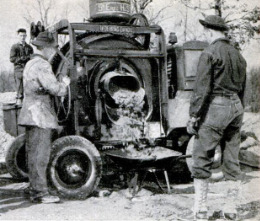

At the front, road construction is mostly

by hand labor, though the combat engineers

are equipped with air compressors, bull-

dozers, and other power machinery which

can be used in some situations. It is planned

to provide modern equipment, most of it

too unwieldy for use at the front, for road

construction in the rear areas.

Bridge building is the most familiar and

probably the most spectacular of the feats

of the engineers. Their technique is whetted

to the point of getting troops across an un-

fordable stream under fire, an ordeal to test

the caliber of any engineer outfit. Such an

attempt would be made ordinarily either at

night or under a smoke screen, and the

technique must be proof against darkness

and confusion, as well as enemy action.

For such work, the engineers are

equipped with assault boats, light skiffs

sturdily built of quarter-inch plywood,

ten of which are carried in a light truck,

nested like the dories on a fishing schooner’s

deck. American officers prefer these to the

inflatable rubber boats carried by the Ger-

man pioneer troops. Each plywood skiff

carries eleven fully equipped soldiers, nine

of them infantrymen and two of them com-

prising the engineer crew.

In a recent test at Fort Benning, Ga., a

complete infantry rifle company was ferried

across the Chattahoochee River, there 320

feet wide and flowing four miles an hour, in

70 seconds through a smoke screen. A small

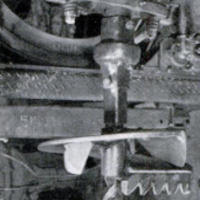

outboard motor is available for use on the

assault boats, but would be useful only in

unusual conditions, as silence and surprise

generally would be prime requisites.

All infantry weapons can be carried in

the individual assault boats except the 37-

mm. antitank gun. Several assault boats

can be quickly assembled into rafts to ferry

the antitank guns and the light trucks which

draw them. For crossing wide rivers, such

as the Mississippi or the Ohio, the engineers

have ponton boats that carry 58 soldiers in

addition to the crew and are driven by

large outboard motors.

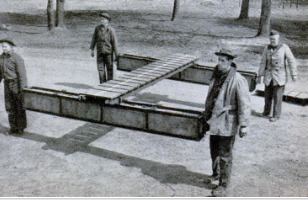

Once the advance party has got a footing

on the far side of a stream, the engineers

rig a sectional footbridge, a duckboard foot-

way between whose slats the water is visible.

Soldiers familiar with this style of bridge

can cross it at a run in daylight. Familiarity

is desirable because, if the soldier looks

down at the water swirling under his feet it

makes him dizzy. Engineers threw a bridge

of this kind across the Chattahoochee at Fort

Benning in ten minutes, including installation of

the anchor cable. Soldiers crossed it at the rate

of 100 a minute.

Four 1%-ton trucks carry floats, duckboard

sections, and cables for the construction of such

a footbridge 432 feet in length. Under favorable

conditions, a bridge of that length can be con-

structed in the field in less than half an hour.

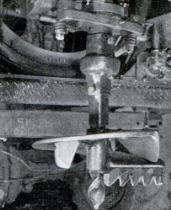

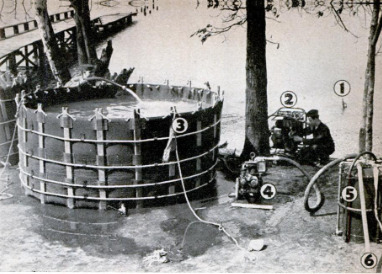

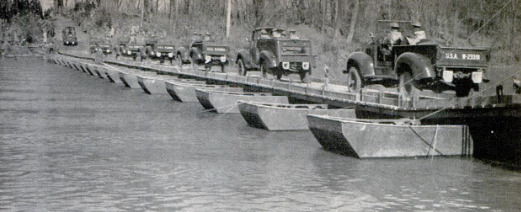

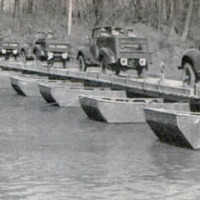

Regular ponton-bridge equipment may be

either light or heavy, the method of construction

being the same with each. Latticed steel or

aluminum supports are used in the shallow

water near shore and a flexible joint called a

saddle or hinge connects that part of the

bridge with the part which is supported by

pontons. Pontons are scow-shaped craft.

The light ones have duralumin frames and

aluminum skins and weigh about 1,400

pounds. Anchored at 16-foot intervals the

bridge they support will carry light field

guns, fully loaded three-ton trucks, and

even light tanks. Reénforced with extra

pontons they can be used by medium

tanks. A light ponton company carries

equipment for 1,000 feet of bridge and

builds about 100 feet an hour. Heavy pon-

tons are similarly made, weigh about 1 1/2

tons, and make a bridge that will carry

155-mm. guns and medium tanks.

The engineers also carry portable bridge

equipment for use where ponton construc-

tion is impracticable, including 72-foot-span

steel highway bridges of 20-ton capacity.

Officers of the Engineer Board at Fort

Belvoir have done much valuable experi-

mental work in camouflage

and a Los Angeles reserve

battalion, most of whose offi-

cers are motion-picture tech-

nicians, has accomplished re-

markable results in the cam-

ouflage of industrial plants.

Engineer officers have much

to do with developing me-

chanical equipment for other

branches of the service. They

have contracted recently for

$17,000,000 worth of search-

lights for antiaircraft artil-

lery. They were instrumen-

tal in the development of a

knee-action trailer for the

transport of 60-inch search-

lights and their power plants.

Four thousand of these trail-

ers have been ordered.

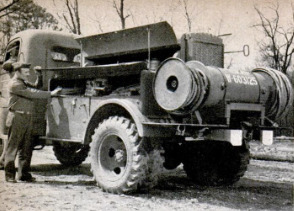

~~ The water supply for

troops, the erection of barbed-

wire entanglements, mine

planting, and tank trapping

are other details which occu-

Py the attention of the engi-

neers. Because of the possi-

bility that supplies of T.N.T.

might be limited in an emer-

gency, the engineers have de-

veloped their own explosive

which is practically as pow-

erful and as safe to handle.

The engineers are organ-

izing a railway operating bat-

talion, which will be stationed

near Alexandria, La., and op-

erate light trains over 90

miles of its own track. Such

a battalion, of about 800 of--

ficers and men, can maintain |

and operate a railroad divi-

sion 100 miles long. Most of

its officers will be railroad |

men who are in the reserve and the rank

and file will be men who have had railroad

experience.

The Army has 20 reserve railway-oper-

ating battalions, the officers of each of them

being from a different railroad. Should it

become necessary to mobilize these skeleton

battalions, the enlisted personnel of each

would be sought among employees of the

railroad furnishing its officers.

Even the recruits whom the engineers

have received through the draft have proved

to be excellent material, primarily because

of the natural mechanical aptitude of Amer-

ican youth. Partly trained men are availa-

ble in thousands for the Army engineers

from among the Reserve Officers Training

Corps students turned out annually by our

universities.

-

Autore secondario

-

Lieut Col. W. F. Heavey (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-07

-

pagine

-

103-112

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik

Screenshot_1.png

Screenshot_1.png Screenshot_2.png

Screenshot_2.png Screenshot_3.png

Screenshot_3.png Screenshot_4.png

Screenshot_4.png Screenshot_5.png

Screenshot_5.png Screenshot_6.png

Screenshot_6.png Screenshot_7.png

Screenshot_7.png Screenshot_8.png

Screenshot_8.png Screenshot_9.png

Screenshot_9.png Screenshot_10.png

Screenshot_10.png Screenshot_11.png

Screenshot_11.png Screenshot_12.png

Screenshot_12.png Screenshot_13.png

Screenshot_13.png Screenshot_14.png

Screenshot_14.png Screenshot_15.png

Screenshot_15.png Screenshot_16.png

Screenshot_16.png Screenshot_17.png

Screenshot_17.png