-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Steel rubber oil battle of the billions

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Steel rubber oil battle of the billions

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

IT LOOKS like some outsider is continually

forgetting that we Americans are a nation

born with the smell of machine oll in our

hair and that if we are crowded too hard we

are liable to stop making electric refrigera-

tors and pretty automobiles and devote all

our attention to turning out the durnedest

flock of airplanes, tanks, and battleships the

world has ever seen. The first time this

happened to ua there wasn't even a rusty

musket_aplece to go round, and foxy old

Uncle Ben Franklin solemnly proposed—

and the other party believed him!—that if

we were to put up any fight at all we would

have to equip at least one regiment of the

Continental Army with bows and arrows.

We were in the subcellar of unprepared-

ness If there ever was such a place, for

there wasn't a single power-driven lathe on

the whole North American continent. Just

the same, from the backwoods forges of the

Green Mountains and from the Lancaster

County hills of Pennsylvania there came an

ever-increasing supply of long-barreled ri-

flea 50 deadly that no person with a grain of

horse sense dreamed of wearing a red jacket

within 300 paces of the muzzle of one of

those nasty things.

Now once more a bad-acting outsider has

forgotten that on no less than five im-

portant occasions in our history we have

changed practically overnight from a nation

of easygoing Yankee tinkers to a tough

army of grim-faced sweating gunsmiths.

Our’ present. national defense program, in

addition to providing us with a two-ocean

navy and the largest and most powerful

mechanized army necessary to meet any

conceivable emergency, also proposes to

supply the tools of defense to any good-

neighbor country threatened by ruthless in-

vaders,

Tt is futile to attempt to appraise this

Gargantuan defense program In terms of

the billions piled on billions it is going to

cost, for the keenest human intellect can

not comprehend the magnitude of even one

billion dollars. However we are warned by

William L. Batt, Deputy Director, Division

of Production, Office of Production Man-

agement, that Germany is now spending the

equivalent of 20 billion American dollars

per year on her war program and that we

must be prepared to exceed that. Or, by way

of comparison, the Panama Canal, which

required ten years to build at a cost of ap-

proximately a half billion dollars, has long

been considered one of the great man-made

wonders of the world; but our present na-

tional defense program calls for the equiv-

alent of the effort necessary to construct

not one but 40 Panama Canals, not in ten

years but in one year!

How desperately unprepared was the

United States for assuming this role as the

arsenal for all good-neighbor nations is re-

vealed by the fact that less than two years

ago almost 70 percent of our metal-work-

ing machinery—on which this vast quantity

of arms must be manufactured—was more

than ten years old. Much of this over-age

machinery has depreciated until it is now of

little use to the national defense program.

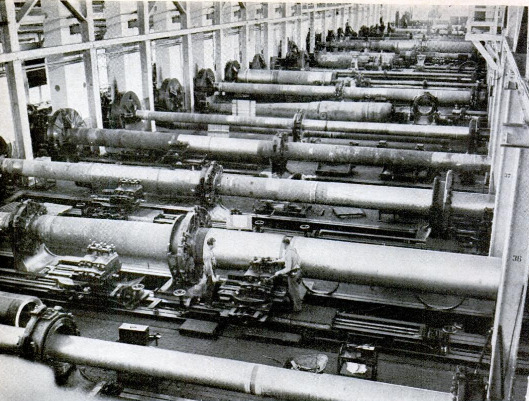

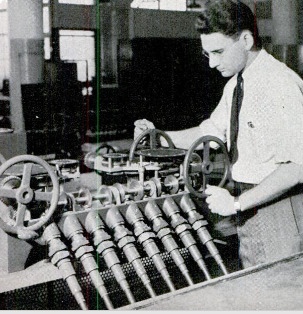

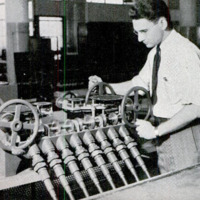

As every machinist knows, you cannot

work to tolerances of a fraction of a thou-

sandth of an inch on a worn-out lathe. To

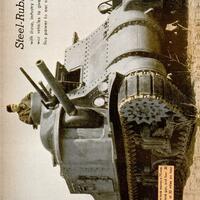

build a ponderous 28-ton tank, which has

the outward appearance of having been

hammered out by an angry blacksmith,

actually requires hundreds of machine op-

erations where errors of just one thou-

sandth of an inch cannot be permitted. To

complicate the problem further, the manu-

facture of machine guns, torpedoes, bomb

sights, and airplane engines involves many

machine operations where an excess error

of one tenth of a thousandth turns an ex-

pensive part into worthless junk.

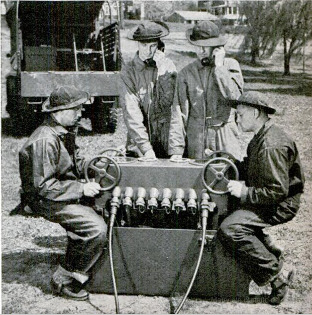

All of which means that vital elements of

the national defense program can be pro-

duced only on new machine tools specially

‘manufactured to super-accurate dimensions

themselves. This has created a frantic de-

mand for what can be called the master

machines of national defense, and our only

source of supply is the American machine-

tool industry which just missed mass bank-

ruptey by the skin of its teeth in struggling

through ten years of depression.

The last good year for the machine-tool

industry had been 1929, when it did less

than 200 million dollars worth of business.

Orders slumped to less than 30 millions in

1933, and at fire-sale prices at that. Just a

year ago the United States Government be-

gan to realize the gravity of its unarmed

position in a world seething with wars of

invasion. Official attention then was di-

rected upon the machine-tool industry.

Which is to say that overnight every maker

of lathes, drill presses, precision grinding

machines, gear cutters, milling machines—

all metal-working machines

needed for the production

of defense articles — was

asked to stoke up that idle

boiler in his power plant

and start building machine

tools on a day-and-night

working schedule.

For the year 1940 the machine-tool in-

dustry boosted production from that all-

time low of less than 30 millions to 400

millions, or an increase of 1,300 per cent!

But this was barely enough to equip a few

pilot lines for the production of defense ma-

terials in limited quantities. The industry

was called upon to double production again

and is well along to fulfilling its promise to

supply 750 million dollars worth of desper-

ately needed master machines for 1941.

‘William S. Knudsen, co-director with Sid-

ney Hillman, of the Office of Production

Management, in a recent address warned

the nation that the production of national

defense materials cannot be achieved on any

easygoing “business as usual” basis. Big

Bill, who when he talks about mass produc-

tion never talks foolishness, listed the fol-

lowing huge production schedule as only

part of the main program:

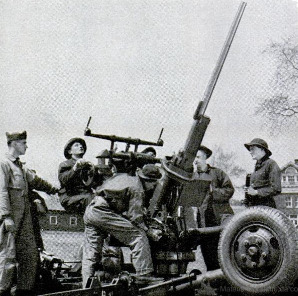

50,000 airplanes (Plus an additional 500

heavy bombers per month ordered re-

cently by the President.)

130,000 aviation engines

17,000 heavy cannon

25,000 light cannon

13,000 trench mortars

33,000,000 artillery shells

300,000 machine gins

400,000 Garand semiautomatic rifles

1,300,000 Springfield rifles, with bayonets

113,000 motor trucks

25,000 trailers

106,000 field telephones

144,000 miles of telephone wire

Plus—a two-ocean Navy, and 200 addi-

tional cargo ships!

Big Bill warns that this is a full-time job

for every skilled worker, for our best man-

agement brains employing our finest ma-

terials and requiring the erection of hun-

dreds of additional factories. This job, he

says, will require 28 billion man-hours of

skilled labor during the next 28 months.

“Every machine shop and every foundry in

the United States which can make even a

piece of something must be enlisted for the

duration.” He might well have added, yes,

and every basement hobby-shop enthusiast

will be called upon to turn out small de-

fense parts after his regular work is done.

Many are the emergency methods being

employed to provide an ample supply of

skilled labor where it will be most needed.

The U. S. Employment Service is calling for

all workers outside the national defense pro-

gram who have unused skill to register im-

mediately at their local state free employ-

ment offices. This appeal was made espe-

cially to older men who had left their trades

and who had become discouraged by trav-

eling hit-or-miss about the country looking

for work. Register at your local state em-

ployment agency if you are a skilled me-

chanic, is the advice right now. Then sit

tight and a defense job will hunt you up.

Public schools throughout the country are

installing secondhand machine tools of the

type most nearly like those used in local

defense plants, so that unskilled workers

can receive basic training and semiskilled

workers can be graded up in skill

Y. M. C. A. night classes have been or-

ganized for the same purpose and many

private trade schools are doing effective

worker training. The National Youth Ad-

ministration and W. P. A. are also con-

ducting worker training courses.

One of the interesting sidelights of the

defense program is the manner in which

newspaper editors have taken the reports of

raw-material prices and supply off the in-

side back page and are now displaying them

as page-one news. The “Big SIX" of the

raw materials these days are Rubber—

Aluminum — Copper — Petroleum — Steel—

Coal. These make the headlines because of

the vast quantities of each consumed daily

by the defense program. Steel, with its

components coke, limestone, and iron ore,

forms the backbone of the defense program,

naturally. The job of moving iron ore from

the upper Great Lakes ports is one of the

really tremendous transportation problems

of the world. More cargo tonnage passes

through the Sault Sainte Marie locks in the

nine months of the Great Lakes navigation

season than is handled in 12 months by the

Panama and Suez canals combined.

Recently aluminum has made headlines

on page one of our newspapers. The domes-

tic demand for aluminum in a brisk busi-

ness year used to run about 300 million

pounds. The demands for airplane con-

struction have increased consumption to

700 million pounds for this year, while the

estimated requirements for 1942, when mass

production of planes is expected to really

get going, may run as high as a billion

pounds. It is only natural then that alumi-

num was the next item after machine tools

placed on the priorities list by the O.P.M.

Copper, like aluminum, is needed in vast

quantities for defense. It is used in the

manufacture of electrical goods—wire, mo-

tors, powerplant generators—and soon

will be in heavy demand as the base metal

for brass cartridge cases. Domestic sup-

plies of copper ore and smelting capacity

are sufficient for almost any possible need.

Petroleum is worrying the Axis partners

far more than it need worry us with our al-

most unlimited supply, which is to be avail-

able not only for ourselves but for all other

nations eligible under the Lease-Lend Act.

Germany and Italy are being forced to carry

on the aggressor's burden of the war with |

only five percent of the petroleum products, |

both synthetic and natural, which the Unit- |

ed States is now producing. |

The Axis partners are especially short of |

100-octane gasoline, of which we have an

abundance and with still more refining car

pacity being built. This 100-octane gas- |

oline means that a supercharged airplane |

engine designed for use with it will deliver

20 percent more horsepower than another

engine using 90-octane gasoline, It so hap- |

pens that 90-octane gasoline is the best Ger- |

many so far has been able to produce, and |

then in such limited quantities that only |

careful rationing, to the utter exclusion of |

nonmilitary consumption, keeps her war

machine from stalling.

Dr. Robert E. Wilson, petroleum expert |

of O.P.M, recently made this report to a |

congressional committee: “The gasoline con-

sumption of Germany during the few weeks |

of fighting in the low countries and France

exceeded the entire consumption during the |

entire first World War.” Yes, our petro- |

leum and 100-octane gasoline production is |

critical—for Germany. |

Other raw materials are being carefully

husbanded by the materials division of |

O.P.M. We use annually more than 500,000 |

tons of chromium ore in the manufacture of

stainless steel, high-speed steel, and special |

steel for ball bearings and nonshrinking die |

steels. A large part of this tonnage of |

chromium ore is used without metallurgical |

refining in the production of firebrick for |

steel-melting furnaces.

At the present time most of our chromite

ore is imported from Africa and the Phil-

ippine Islands, over trade routes that may

be interrupted at any moment. But a year's

reserve of high-grade ore, over and above

current arrivals from abroad, gives us suf-

ficient leeway to develop American low-

grade chrome-ore deposits and expand our

existing ore-treating plants.

Curtailment of our tin supply, which

comes from British Malaya and the Dutch

East Indies, is also possible. But here again

we have created a reserve to last a year

with careful rationing. Meanwhile our

South American neighbor, Bolivia, is pro-

viding us with 18,000 tons of ore per year.

The greater part of the 90,000 tons of tin

we import annually goes into the countless

millions of tin cans used by the food-can-

ning industry. New lacquer coatings for

untinned sheet steel have proved adequate

as a substitute on food containers. Glass is

also available—as the farm wife well knows

—as a substitute for tin cans, and at slight-

ly higher cost silver could be used. It is

estimated that the cost of a can of tomatoes

would increase not more than three cents if

packed in a silver-plated can—extra for

engraving your initials, of course.

Since every metal-working machine must

have efficient cutting tools, tungsten also

has become a strategic raw material. High-

speed tool steel requires 18 percent metallic

tungsten to make it able to peel off red-hot

steel chips without losing its temper. Most

of the 500 tons of high-grade tungsten ore

we import per year comes out over the long

and tortuous Burma Road from the interior

of China. This source may be cut off at any

time, as it recently was when the Burma

Road was closed temporarily. Our reserve

supply is almost nil, aside from what high-

speed steel scrap is in the hands of scrap-

metal dealers and the steel mills. We have

a five months’ supply at best, but again

fortunately we have a substitute. This is

molybdenum. One mountain in Colorado |

can supply all the molybdenum we will ever

need as a substitute for tungsten in high-

speed steel.

Another development of metallurgy has |

provided an even more efficient cutting met- |

al than tungsten steel. This is tungsten car- |

bide. Small bits of tungsten carbide when

welded to less expensive steel shanks actual-

ly cut metal faster than 18-percent tungsten

steel, and also hold an edge much longer be-

tween regrindings, thus saving at least 20 |

percent of the time a machine is idle while |

tools are changed. The really important

feature of tungsten carbide, however, is the

fact that one pound of tungsten carbide re- |

leases 100 pounds of precious metallic tung-

sten for the more essential defense needs—

such as tips for armor-piercing shells.

Some 72 raw materials are essential to

the national defense program, with now and |

then a material like magnesium—a metal |

lighter than aluminum and now being used

in increasing quantities for airplane-motor |

castings—making the headlines for a day or

two, only to be forgotten by the public as |

soon as it learns that a new magnesium |

plant just recently erected on the Gulf of |

Mexico is tapping the unlimited reserves of |

this metal in sea water! Zinc will be men- |

tioned in connection with what agriculture |

is contributing in the way of raw materials

for defense. There still remain to be men-

tioned antimony, industrial diamonds, man-

ganese, nickel, beryllium—a new metal em- |

ployed in hardening armor plate and for |

machine-gun parts—cobalt, graphite, as-

bestos, cotton, mercury, and so on down

through the list. In none of these materials

could a serious shortage arise.

Of all defense raw materials obtained

from distant foreign sources, “rubber” is

the fighting word that would instantly send

the United States battle fleet steaming west-

ward with its decks cleared for action at the

first authentic news that some enemy power

was intercepting American merchant ships

laden with crude rubber. Our annual con-

sumption of crude rubber is something near

700,000 long tons, mostly imported from

British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies.

This supply may be cut off at any time.

Meanwhile the best minds studying the

rubber problem are busy devising a second

line of defense, should our supply of crude

rubber from the Orient fail. Excellent syn-

thetic rubber products are being made in

limited quantities from petroleum and vari-

ous gases in combination with other ele-

ments. Synthetic rubber production at

present meets less than two percent of our

minimum requirements, while

3,000 tons of guayule rubber,

extracted from a shrub that

grows wild in Mexico and our

own Southwest, and about

20,000 tons from South Amer-

ica. constitute our only other

sources of crude rubber.

1t is obvious that our rub-

ber problem would be serious,

if not critical, if it not were

for the fact that in the junk

yards of America and hang-

ing from nails in almost

every private garage, there

are hundreds of thousands of

tons of reclaimable rubber in

discarded automobile tires.

Chemical and mechanical

processes now can extract this

scrap rubber and restore it

largely to its original state

of usefulness.

Paul W. Litchfield, chair-

man of one of the largest

rubber-processing plants in

the world, estimates that

from these garage nails and

junk piles a two years’ sup-

Ply of vitally needed rubber

can be reclaimed. Don't be

surprised some day to hear a

voice over your radio asking

you to go out to the garage

and unhook that old tire

from the nail and turn it in

as your personal contribution

to the national defense pro-

gram.

The defense role of chemurgy, the new

science of converting farm products into in-

dustrial materials, is described elsewhere in

this issue. From soybeans it makes plastics

that will release much-needed zinc for the

‘manufacture of cartridge-case brass. Soy-

bean ofl will yield stearic acid for use in the

‘manufacture of tires and to increase the

supply of glycerin for explosives. So the

farm tractor may well be considered as en-

listed for national defense, side by side with

its tough big brother the 28-ton tank.

Machines and raw materials are vital to

the national defense program. But it is man-

power—the manipulation of machines and

processes by skilled hands and intelligent

brains—that must be counted on to build

the complicated weapons we need.

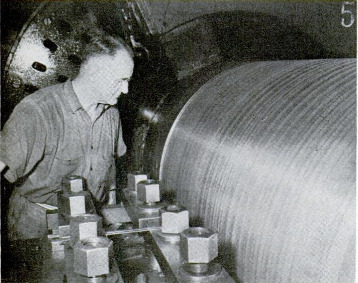

Not much over two years ago a skilled

‘mechanic over 40, unlucky enough to be out

of a job, was considered all washed up and

with no future but a pick-and-shovel job on

a relief project. All that has been changed

by the national defense program.

Recently the manager of a large saw

works producing lightweight armor plate

for fighting planes pointed out to a visitor

a giant plate-edging machine being run by

a spry old man,

“We bought that machine secondhand be-

cause we couldn't get delivery of a new one

in time,” explained the manager. “But we

got a bad scare when we discovered that not

one of our 800 men knew beans about op-

erating this monster. Then into our em-

ployment office walked a white-haired old

mechanic who said he had been reading in

the papers how the defense program needed

all the machinists it could muster. Would

we let a man of 75 show what he could do?"

‘The plant manager pointed to the old man

on the big machine. “It sounds like a fairy

tale, but our employment man played a

hunch and took this old-timer out into the

plant and showed him this machine. ‘If you

can make that balky thing walk the dog,

sald our employment man, ‘you're hired."

“For a moment,” went on the plant man-

ager,” the old man just stood there fighting

back the tears. Then he said, ‘Mister, ten

years ago I was laid off because the factory

where I worked went bankrupt and sold off

all its machinery at auction. That big ma-

chine, standing right there, is the one I used

to run. Mister, I'll make that machine knit

lace curtains if you say the word!”

As more and more new machinery ar-

rives and still more plants get rolling on

mass production of defense materials the

cry will be for more and still more skilled

men. Otto W. Winter, chairman of the

Emergency Training Committee, American

Society of Tool Engineers reports: “Skilled

labor and technical labor requirements re-

veal a shortage of 1,250,000 men.”

Other surveys indicate that to meet the

peak still to come an additional 4,000,000

skilled men will be needed. The training and

morale of this vast army of defense workers

is already recognized as being of equal im-

portance and worthy of equal praise to that

of the men in uniform. A nation of 130 mil-

lion free people has spit on its hands and is

tackling the problem of building an over-

whelming stock of all the tools of war.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Ray Millholland (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

57-62

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941