-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Navy's triple threat: fire power, speed and armor

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Navy's triple threat: fire power, speed and armor

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

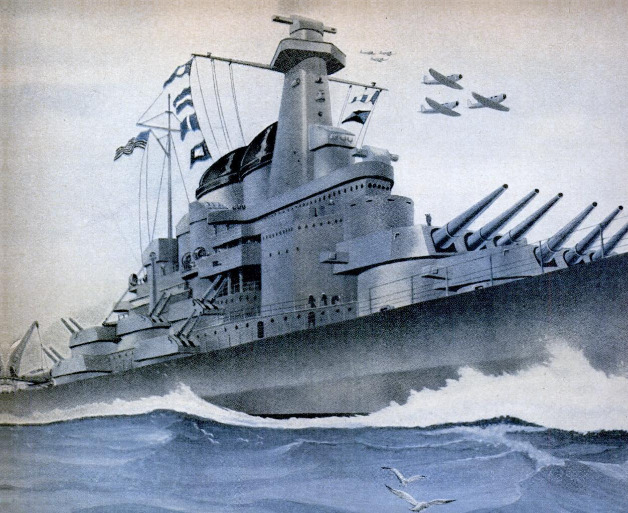

REINFORCING the United States Navy

at a time when they are extremely

welcome, the two most formidable

battleships in the world have just been

placed in commission. Sister ships of 35,000

tons each, the mighty North Carolina and

Washington excel anything else afloat in

their combination of guns, speed, and armor

—the three vital elements of a ship of

the line.

Nine 16-inch rifles belch a ten-ton broad-

side of steel and T.N.T. to a distance of

20 miles. A “designed” or rated speed of 27

knots keeps up with today’s demand for

faster and faster ships—and battleships,

like race horses, have a way of being con-

servatively rated by their owners before

they go into action. Either of the new ships

could be struck by as many as five torpe-

does and keep right on fighting, it has been

estimated, because of their antitorpedo

bulges and extreme subdivision into water-

tight compartments. “Belt” or side armor

reportedly 16 inches thick protects maga-

zines and machinery from shellfire, and ten

inches of deck armor resists the heaviest

bombs from the air.

Manned by 1,500 officers and men, each

750-foot floating fortress mounts three huge

turrets, of which the rotating part weighs

1,500 tons, or about as much as a modern

destroyer. Secondary and antiaircraft guns

embody latest designs—of which more later.

Three to four planes, launched from cata-

pults, spot artillery fire. Geared turbines

that drive quadruple screws consume

< enough power for Jersey City, N. J, or

Houston, Tex. A new steering system, with

twin rudders, is reported. Preparation of

thousands of working drawings for the

ships took two years in itself, and the result

is called the finest of 140 different kinds of

battleships. Owing to a changed method of

figuring tonnage, the Washington and North

Carolina exceed the size of their “43,200-ton”

namesakes which were scrapped when par-

tially completed, in postwar disarmament.

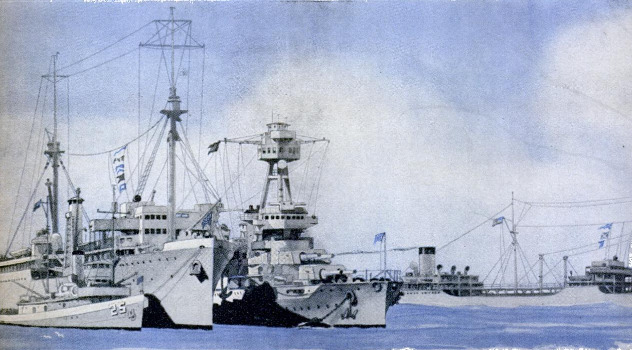

In hundreds of items, from sailors’ uni-

forms to superdreadnoughts, the Navy has

been modernizing itself for today’s style of

warfare. Sidelights as diversified as these

might be picked at random from a bulletin

board of recent naval news:

Sailors on shore leave no longer will ad-

vertise the whereabouts of any particular

warship by its name on their cap ribbons.

The words “U. S. Navy" are now being

substituted.

Because white uniforms have been found

t00 conspicuous aboard ship, the “camou-

flage” of khaki-colored working uniforms

has been adopted.

Records fall as construction leaps a year

‘ahead of schedule for battleships and nearly

as much for cruisers.

Veterans of Mississippi River traffic soon

will blink their eyes at the sight of U. S.

submarines, built at a Wisconsin shipyard

and traveling down OF Man River to the

Gui.

Lieutenant Commander J. J. Tunney, none

other than the Gene Tunney of heavyweight

boxing fame, takes charge of physical train-

Ing for Navy men, and officers keep fit with

an exercising machine of his invention.

Vessels of the Atlantic Fleet get a new

war paint of darker gray.

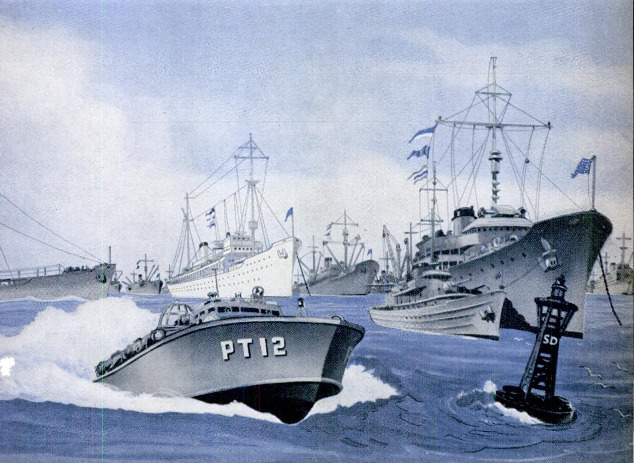

Crews of “mosquito” patrol torpedo boats

devise hand signals for maneuvers at 72

miles an hour, a pace that outrules the

traditional signal flags.

Latest of the Navy's long-range patrol

‘Bombers mount three power-driven gun

turrets, a system inspired by war ex-

perience abroad.

Dozens of private yachts, sold or pre-

sented to the Navy, join the sea forces as

gunboats, sub chasers, and patrol boats. A

car ferry becomes a mine layer.

"Plans advance for converting cargo ships

Into miniature aireraft carriers.

Radio-controlled planes simulate dive

bombers for Navy target practice—and are

brought down with gratifying frequency.

New and secret inventions detect sub-

marines, warn of approaching ships and air-

craft, and aid in high-speed mine sweeping.

Variable-pitch propellers for warships are

being developed. Like airplane propellers,

they automatically change their “bite” in

accordance with load, assuring maximum

efficiency at all times.

Here is some bigger news: According to

Rear Admiral S. M. Robinson, chief of the

Navy's new Bureau of Ships, three out-

standing developments—protection against

magnetic mines, more and better guns, and

antiaircraft measures—have transformed

what naval men now call the “old” fleet

of July, 1940.

Working swiftly and quietly, naval ex-

perts had 319 U. S. warships and auxiliaries

fitted to neutralize magnetic mines by as

early as February of this year, and work

on 115 more vessels was under way. The

system encircles a ship with a band of wires

carrying electric current, which counter-

acts the magnetic effect of the metal hull

and keeps the mines from exploding. A

curious phenomenon in that magnetic com-

passes go awry when the device is turned

on, but this does not matter to modern ships.

equipped with gyro compasses, which are

unaffected,

First installations of the antimagnetic “de-

gassing girdle” —named after the gauss,

a magnetic unlt—were temporary. Early

thin year, the Navy perfected a permanent

de-gaussing system, costing an average of

$20,000 per vessel, that will be good for

the life of the ship. Replacements will bo

made as vessels come In for overhaul, but

already the Navy feels satisfied that It has

conquered the magnetic-mine menace.

Guns for warships, guns for some 115

naval auxiliaries that go unarmed in

“normal peacetime,” still more guns for

vessels taken over from commercial mervice

—these have been another key part in

putting the fleet on a war footing.

Pride of the Navy is its new five-inch gun

for destroyers and, as secondary armament,

for cruisers and battleships. This double:

purpose weapon can be trained on sea

targets, or elevated to extreme angles for

antiaireratt fire. Turrets mount the guns

in pairs. They supersede a shorter-barreled

five-inch gun, which in turn replaced a

three-incher. Remarkable range and rapldi-

ty of fire distinguish the newest guns. Be-

sides installations on battleships, they have

been placed on the latest crulsers and on

all destroyers. They may clearly be seen in

the painting of the North Carolina on pages

86 and 87, installed at two levels along the

side of the ship,

For defense against dive bombers, the

U. S. Navy has developed a new 1li-inch,

‘multiple-barreled pom-pom gun or “machine

cannon,” according to Rear Admiral W. R.

Furlong, chief of the Navy's Bureau of

Ordnance. A burst of its ultra-rapid fire

fills the air with explosive one-pound shells,

capable of winging or completely demolish- |

ing a plane with a single hit. Four to eight

of these deadly batteries, placed at stra-

tegic posts on the topside, go into action

under centralized director control. First

deliveries have been slower than the Navy

would like, but it expects to get at least 400

of the guns this year.

“Splinter protection,” the third main ad-

vance, shields formerly exposed members

of the crew from fragments of bombs, and

from pieces of steel that a bomb may knock

off. The war has shown this flying debris

far more dangerous to personnel than had

been expected. Therefore, as much topside

armor as can be installed, without impair-

ing the stability of the ship, has been

adopted to protect U. S. gun crews, ob-

servers, and signalmen. As this is written,

most of our 58 large warships, including all

battleships, have been fitted with splinter

protection.

New ideas in power plants occupy a

prominent place among other modern naval

developments, Operating under 600 to 800

pounds of steam pressure, compared with

the 150-pound pressure of most ships in the

last war, the North Carolina and Washing-

ton are our first battleships employing the

high-temperature, high-pressure systems al-

ready tried out successfully in smaller U. S.

warcraft. Diesel engines for major war-

ships, introduced in the German pocket

battleships, are rated as a development

worth watching. And within a few months,

the Navy is Scheduled to receive a gas

turbine, which, according to Admiral Robin-

son, “is revolutionary in design and promises

a new era in power for propulsion of ships.”

It will be subjected to extensive trials, first

in the Engineering Experiment Station at

Annapolis and then in a ship. As many

readers of this magazine will recall, a gas

turbine works much like a steam turbine,

but the steam is replaced by a searing blast

of vapor from ignited fuel. Practical dry-

land power plants using gas turbines have

been developed only within the last few

years (P.S.M., Dec. '39, p. 80), and use of

a gas turbine to propel a warship would be

an innovation of the first magnitude.

What the Navy calls a “projectile pro-

gram” has been carried on for three or four

years. Improved naval shells have been

produced by special heat treatment, which

prevents the missiles from breaking up

when they meet their mark. As Admiral

Furlong puts it, “It gives you the ability

to pierce a given thickness of armor plate

at a much greater range.” Providing battle-

ships with 16-inch and 14-inch armor-pierc-

ing shells of the new type has come first

in the program, which also includes eight-

inch shells for the guns of heavy cruisers.

“A recent experiment where one of our

battleships actually fired on another one,”

Admiral Furlong says, “clearly showed that

improvements could be made in the con-

struction of gun turrets.” Not officially

identified in this startling statement, the

target ship may have been the radio-con-

trolled Utah, capable of operating without

a crew aboard. The Navy is taking ad-

vantage of the test's results on each battle-

ship and cruiser in service. What they

were remains its secret.

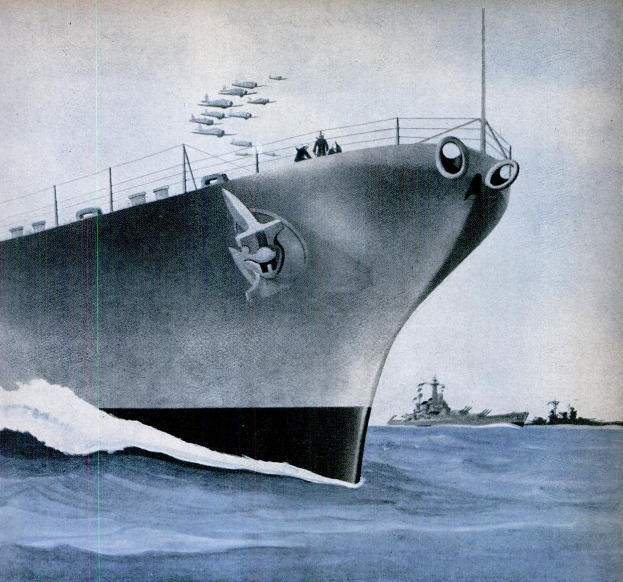

Among the most novel of fighting ships

under construction and on order for the

Navy will be our first battle cruisers—the

recently contracted-for Alaska. Samoa,

Havwaii, Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

From their cost of $53,400,000 apiece for

hull and machinery alone, the only detail

made public, naval experts guess them to

be ships of between 25,000 and 27,500 tons,

mounting 12-inch or 14-inch guns. If so,

they will be comparable to the German

ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which

have been used as fast sea raiders.

What distinguishes a battle cruiser from

a battleship of equal gun power is superior

speed, gained at the sacrifice of a battle-

ship's massive armor. And now that engi-

neering advances have given modern battle-

ships what used to be considered battle-

cruiser speed, the latter will have to be

stepped up in turn. When the new 35,000-

ton German battleship Bismarck met Eng-

land's 42,100-ton battle cruiser Hood, since

1920 the world's largest warship, the contest

was equal in guns and speed—but the Hood's

armor failed to stop a shell that exploded its

magazine and sank it. Presumably the new

American battle cruisers, capable of de-

stroying pocket battleships and cruisers,

will have exceptional speed to keep out of

the way of more powerful adversaries—

which will have to be dealt with by our

battleships.

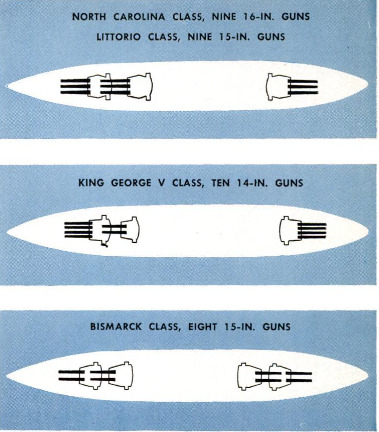

Arrangement of big-gun turrets offers a

striking example of changing naval designs.

For American battleships, which formerly

carried equal armament fore and aft, the

North Carolina class represents a new

departure. It concentrates two thirds of its

guns in forward turrets, giving added fire

power on the offense,

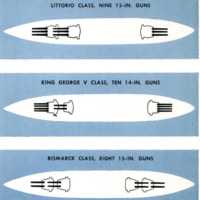

Comparison suggests itself with the new

35,000-tonners of foreign design. Italy's

Littorio class has a similar arrangement of

turrets, but inferior armament—nine 15-

inch instead of 16-inch guns.

England's King George V class adopts a

different method to bring the most intense

gunfire forward. Quadruple 14-inch gun

turrets fore and aft are reinforced by a

pair of guns of the same size in a second

forward turret.

France's ill-fated Richelieu class repre-

sents an all-forward turret arrangement,

unique except in Britain's smaller Nelson

and Rodney. Even before the war, British

naval maneuvers demonstrated its danger-

ous weakness in leaving the stern unpro-

tected. The battered Richelieu, last re-

ported in use as a floating battery, mounted

eight 15-inch guns in quadruple forward

turrets.

Germany's new Bismarck class carries the

same armament in two turrets forward and

two aft. Japan's smaller Nagato class

mounts eight 16-in. guns, similarly dis-

tributed.

A glance over these figures will clearly

show the superior armament of the U. S.

35,000-tonners, with Britain's a good second,

as measured by the total power of their

guns. The American ships even have the

greatest total diameter of guns; and a pro-

Jectile’s bulk increases so rapidly with di-

ameter that a 16-inch shell weighs half

again as much as a 14-inch shell.

In the U. S. battleship program, four more

of the North Carolina class are building, and

due for completion next year. They will be

followed by six even mightier 45,000-ton

craft of the Iowa class. These 880-foot

ships, designed to equal or outclass Japan's

much-rumored vessels of 40,000 tons or

more, will use their added tonnage for

speed. Keels have been laid for four of

them. Thirty percent of their steel work

will be welded, saving still more weight

for propelling machinery, which is rated at

the unheard-of figure of 200,000 horsepower

—which is nearly twice that of the North

Carolina.

If that seems like something, hold your

hat. Five more U. S. battleships of the

Montana class, all contracted for, will dis-

place 58,000 tons apiece. Superdreadnoughts

seems a mild word for them. Probably too

gigantic to risk launching by sliding down

shipbuilding ways, they may be set afloat

in special shipbuilding basins—another sub-

ject upon which the Navy prefers not to

elaborate. For armament, twelve 16-inch or

18-inch guns are talked about. To naval

architects these will be “dream ships,”

virtually ending decades of compromise in

apportioning weight for guns, armor, and

propelling machinery. Hulls of such mon-

ster size will carry all that could be desired

of each. The result will be the long-pre-

dicted “ultimate” or ideal battleship, the

monarch of the high seas.

And, as someone has said with grim

humor, “People understand battleships.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Alden P. Armagnac (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

86-91

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941