-

Titolo

-

Army's new system

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Army's new system

-

extracted text

-

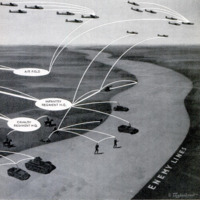

THE heavy tanks and dive bombers hit

the line, smash an opening. Through the

gap rush the armored divisions, the

light and medium tanks and armored cars,

fanning out, a fast backfield running inter-

ference for the infantry.

Fifty miles, 100 miles and more a day the

mechanized columns speed over the vast

grid map of battle. Their slashing end runs

flank the enemy at 35 and 40 miles an hour.

In Flanders, France, Greece, Libya, the

dashing pace of modern war has come more

and more to resemble football in a broken

field.

But the comparison breaks down com-

pletely at one point: there is no time out for

a huddle between plays. Signal communi-

cations, the army's nerve system, must be

maintained at breakneck speed continuously.

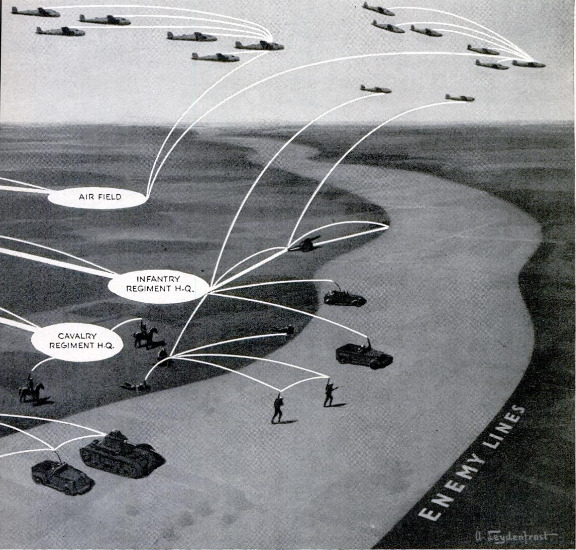

Observation planes, bombers, scout cars,

tanks, artillery, infantry must remain in

quick, instant contact with the high com-

mand; otherwise an integrated, intelligent

striking force becomes a disjointed rabble.

The marvels accomplished by the German

Army in the last two years have set our

political orators shouting for tanks, planes,

guns—a cry with which everybody agrees.

But every military man knows that the real

marvel of the German assault has not been

merely its preponderance in engines of war,

but also the precise codrdination with which

this vast amount of equipment and man-

power was used.

The Germans learned their lesson in 1914.

Entering the first World War with a primi-

tive signal corps comprising only nine bat-

talions of telegraph troops, they failed to

carry out their original assault according to

plan, largely because their communications

broke down. No such fault developed in

1940, though lines of communication were

stretched far beyond what seemed their breaking

point. That army's nerve system extended to its

very fingertips, as_ exemplified in the attack on

Fort Eben Emael. The sudden fall of that strong-

hold was one of the shocking mysteries of the at-

tack on Flanders, but it became less mysterious

when word came through that the assaulting en-

gineers, tanks, and air force were in contact by

radio throughout the attack with parachute troops

landed inside the fortifications. Even with this in-

tensive use of radio, wire channels were not neg-

lected. Right behind the tank columns came the

signal trucks, unrolling their telephone and tele-

graph wire.

Today the Signal Corps of the U. S. Army, under

Major General Joseph O. Mouborgne, is engaged in

an expansion program big and complex enough to

wrinkle the brow of any industrialist. America’s

vast prospective motorized and mechanized Army

must be provided with a communications system of

multiplicity and complexity undreamed of in the

World War. For every time you double the speed

and mobility of a military outfit you multiply its

communications problem. “And the new miracles of

radio—used only when more secret message chan-

nels are not available, must be superimposed on all

the old, sure methods—telegraph, telephone, pyro-

technics, messengers, and pigeons.

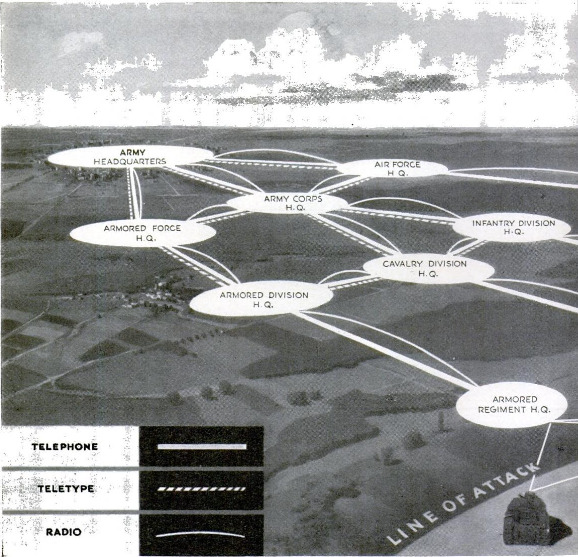

Some notion of the task involved may be obtained

by merely glancing at the radio equipment of a

single armored division. The United States armored

division is at present composed of approximately

the following forces, all carried by armored ve-

hicles:

A headquarters (in three echelons, which in op-

eration may be separated by as much as 60 miles);

1 reconnaissance battalion; 1 armored brigade of

three tank regiments, two light and one medium; 1

infantry regiment; 1 battalion of field artillery

(four batteries); 1 battalion of engineers; 1 signal

company; and service elements.

To perform its mission, and make it instanta-

neously responsive to commands while operating at

high speed, this aggregation of striking power has

basic signal equipment of about 700 radio sets, not

counting those of codperating observation planes

and dive bombers. Each commanding officer is con-

nected with his subordinates, and coperating units

of infantry, artillery, and air force maintain liaison,

through a system of nets tuned to separate radio

frequencies.

The number of nets required for this system is a

total of at least 41, plus a number of ultra-short

‘wave channels for short-range voice transmitters

within infantry and artillery units. Remember that

this is just for one division, a relatively small part

of a modern field army. Take an armored corps of

several divisions, follow it up with motorized di-

visions and divisions of foot soldiers; then put a

hostile army in the same field, also using radio; and

you have an air traffic problem which makes the

difficulties of the F.C.C. with wave lengths seem like

child's play.

Only the most rigid

control and precise calibration of instru-

ments prevents this system from becoming a

mere babble of waves in a jammed atmos-

phere. Most of the sets operate as silent re-

ceivers, authorized to transmit only in emer-

gencies. Even so, the whole matter takes on

a complex precision which is almost beyond

the imagination of those of us accustomed

only to the fuzzy tuning of our home radio

sets. The frequencies used, and the tech-

niques of avoiding confusion, are among the

closely guarded secrets of the Signal Corps.

But one method which seems sure to make

forward leaps is frequency modulation, the

new staticless form of radio. FM not only

adds new channels; it also eliminates the

interference set up by the ignition of thou-

sands of near-by gas engines.

As thus shown in the Armored Force, and

also in the air squadrons, the instruments of

communication tend today to come more and

more into the hands of the combat soldier,

intensifying the Signal Corps’ réle as a body

of specialists superimposed on the Army's

basic organization. The most striking ex-

ample of this is the tiny voice transmitter,

powered with dry cells, known as the

“walkie-talkie.” Carried in a pack, this

little radio telephone weighs only 25 pounds,

half a soldier’s ordinary load.

Obviously adapted to such melodramatic

uses as those of parachute troops or small

reconnoitering parties, the “walkie-talkie”

has far more basic value. The artillery, for

instance, has responsibility for maintaining

liaison with the infantry it is supporting;

and in the World War more artillerymen

were shot in repairing telephone lines to the

trenches than in any other way. Today such

losses would be unnecessary. When the

wires go out, the radio takes over.

Twenty years ago, when the infantry

first asked for the development of a radio

which one man could easily carry, the idea

was an utter technical impossibility. But

years of research by the Signal Corps lab-

oratories, as well as by industrial designers

who worked out the little spot-news broad-

casters used by the radio chains, have de-

veloped devices of amazing simplicity.

Today the walkie-talkie is standard equip-

ment for front-line troops, and is but the

smallest of a whole family of instruments

grading up to the heavy fixed-station trans-

mitters, all specially and ruggedly designed

for rough usage in the field. In the World

War, a radio station was a heavy affair with

a gas engine and hundreds of pounds of

equipment. Today, a front-line transmitter

with range of several miles is hardly twice

the weight of a walkie-talkie, its antenna is

a small loop, and its power is provided by a

tiny generator turned by hand cranks.

‘These small outfits are designed, provided,

and maintained by the Signal Corps of the

Army, which operates in units attached di-

rectly to the higher headquarters. In oper-

ations the Signal Corps is responsible for all

communications down to the next unit below

division headquarters, brigade or regiment

as the case may be. The smaller units han-

dle all their own signaling, with equipment

provided by the Signal Corps.

The signal service of a field army includes

two signal battalions and several specialized

companies; an army corps has one signal

battalion; and each division has a signal

company attached to headquarters. These

units, broken down into specialized platoons

and small teams, are capable of a great va-

riety of simultaneous operations.

Ordinarily the Signal Corps amounts to

about three percent of the Army, but under

the pressure of the last few months it has

expanded even more rapidly than the mili-

tary establishment as a whole. Last spring

it amounted to 35,000 men and 1,300 officers,

exclusive of National Guard units, and its

training post at Fort Monmouth, N. J., had

multiplied from a strength of only 800 to

nearly 12,000.

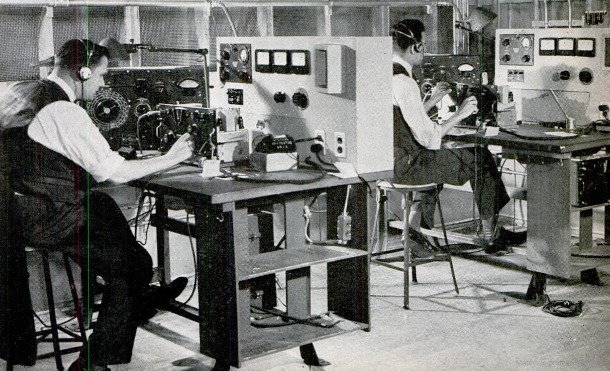

Here signal technicians are being turned

out by mass production. The Signal School

gave specialized three-month courses during

the last year to more than 3,000 enlisted men

and officers, and is scheduled to put through

at least 6,000 more during the year just be-

ginning. For newly inducted men a Re-

placement Training Center was opened in

March, and in the next three months gave

basic training to nearly 6,000 as linemen,

radio, teletype, and telegraph operators.

Fairly competent operators, for radio, tel-

egraph, and teletype, can be turned out in

three months; and they speed up with

further practice. Accuracy is the primary

thing, for a military message has no sense

to guide a man in sending it. Except when

an armored column is moving so fast that

secrecy is no object, and radio can be “in the

clear,” military messages are sent in code

(with groups of letters substituted for

other meanings) or in cipher (with letters

substituted for those of the actual message

so as to make an apparently incoherent

jumble). The typical military message is a

Sequence of five-letter “words” which are

merely mixtures of letters with no apparent

meanings. The Signal Corps has mechanical

devices which speed up the process of mix-

ing and unmixing the cipher, but that is no

help to the operator, who must be contin-

ually transmitting a letter-perfect stream of

alphabet soup.

The ingenuity of cryptography is exceeded

only by the art of cryptanalysis, the solving

of the secret ciphers of the enemy. This

whole field is one of the special concerns of

the Signal Corps, not only as to maintaining

the security of its own messages, but also

breaking down and reading the codes of the

enemy. The enemy is supposed to be so good

at this kind of puzzling that any code can be

broken down in from six hours to three days

at the most. In enciphering messages it is

routine, in addition to changing the key fre-

quently, to change the method of jumbling

the letters, after every five words.

Attached to each field army is a radio in-

telligence company, capable of operating

many stations on a 24-hour basis to inter-

cept enemy messages, and also a number of

radio direction-finding stations over a front

of 35 miles. A radio direction finder, with

a loop antenna rotating on a vertical axis, is

able to take a precise bearing on any select-

ed station. With two or more such bearings

from different points, the location of an

enemy transmitter may be obtained very

quickly, in much the same manner as ships

navigate by radio bearings.

America has real reason, In this emer-

gency, to be thankful that its communica-

tions system is the most highly developed in

the world. Its related industries have de-

veloped rapidly during the last quarter cen-

tury, and all the new devices of printers, tel-

etypes, facsimile, multiple circuits are quick-

1y adaptable to army use, to carry the heavy

traffic between headquarters. The skills of

wire management and maintenance are so

widespread that it is almost no problem to

get the men for the job.

But radio is the competitive frontier, and

here at the moment there is no reason for

complacency. A nation of knob-turners does

not thereby become a nation of radio tech-

nicians. Repair for the radios of thousands

of tanks is bound to become one of the

Army's greatest problems,

But that need won't become acute until

the tanks start rolling off the assembly line,

and then the radio industry will really come

into its own as a basic factor in defense.

America can tell the world that its radio in-

dustry produced 11,000,000 radio sets last

year, and 110,000,000 tubes, an increase of

2,000,000 sets from the year before. These

small army portable sets are not very com-

plex. The industry can easily supply them,

and repair men too.

-

Autore secondario

-

Hickman Powell (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

Eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1941-08

-

pagine

-

92-95,216-218

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Sami Akbiyik