-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Poison gas defense is the army chemist's job

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Poison gas defense is the army chemist's job

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

Gas covers a far greater area, pound for

pound, than high explosives or other impact

weapons. Thus, one medium bomber, carry-

ing four 550-pound bombs filled with a non-

persistent gas such as phosgene, under

favorable conditions can establish in a sin-

gle flight an effective concentration over

four circular areas, each about 300 yards in

diameter. At this rate, a squadron of

twelve bombers in one flight can cover a

square mile with such a concentration that

every unprotected person would become a

fatal or serious casualty.

If persistent gas such as mustard were

employed in small (22-pound) bombs, one

medium bomber could create in a single

flight 100 centers of contamination, each ap-

proximately 40 yards in diameter. The area

thus covered (126,000 square yards) is the

equivalent of five average city blocks. If the

persistent gas were sprayed, instead of

dropped in bombs, each plane could cover an

area a mile long and 1/6 mile wide, and one

squadron of 12 bombers, an area of two

square miles. While the concentrations thus

produced would cause but few deaths, nearly

every unprotected person in the area cov-

ered would become a casualty.

In addition to its greater coverage, gas

also would have a very marked searching

effect. By filtering through cracks and

crevices and flowing into every nook and

cranny, it reaches every part of the area

covered, even places protected from the fire

of other weapons. Persistent geses (such as

mustard) also have a long duration of action

and remain effective over periods of time

which vary from several hours in summer

to several days in winter. Many gases also

have high powers of penetration. Thus mus-

tard gas readily goes through all ordinary |

clothing and even through leather and rub- |

ber; it also quickly soaks into wood and con- |

crete and is exceedingly difficult to remove.

Finally, gas has a powerful psychological

effect because it is usually invisible and its

powers and limitations are not generally un-

derstood. The human mind instinctively

fears the unseen and unknown, and the

harmful effects of gas are thus greatly mag- |

nified by the imagination. This moral effect |

is of special importance in gas attacks on |

the great cities, as it may easily lead to

widespread panic and demoralization of the

civil population.

Owing to the characteristics mentioned |

above, gas is a powerful defensive weapon.

It may be quickly laid down by low-flying

attack planes and chemical tanks in broad

belts across a front to be defended and thus

provide a serious barrier to enemy attack-

ing troops which must traverse such con-

taminated zones. While it is, of course, pos- |

sible to gasproof tanks and other mech-

anized vehicles, it is exceedingly difficult to

keep them gas-tight under battle conditions

and widespread casualties to mechanized

troops would undoubtedly result from trav-

ersing gas-contaminated areas. Also, the

wearing of masks and protective clothing

materially reduces the combat efficiency of

troops, especially where they are compelled |

to wear such equipment for many hours at

a time of great physical exertion.

Recognizing the seriousness of gas at-

tacks, especially upon the large cities, every

country in Europe has taken far-reaching

‘measures to protect its army and urban pop-

ulation from this threat.

In addition to providing means for warn-

ing soldiers and citizens of impending gas

attacks and educating them as to the nature

of gas and what to do to protect themselves

against it, chemical defense comprises three

general measures of protection: (1) gas

masks and protective clothing for each in-

dividual: (2) gasproof shelters or refuge

rooms for groups of persons: and (3) de-

contamination of ground, buildings, and ma-

terials in contaminated areas.

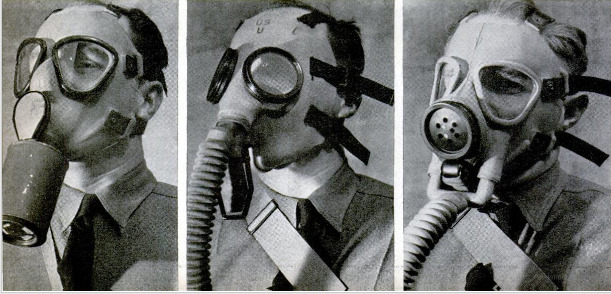

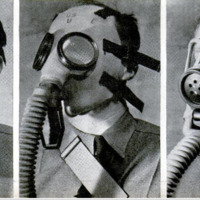

‘The principal gas masks used in the Amer-

ican Army are the standard service mask

for combat and the training mask for train-

ing troops. These are supplemented by the

issue to certain troops of special types of

‘masks, such as diaphragm and optical masks,

which enable them to carry on their combat

duties when masked.

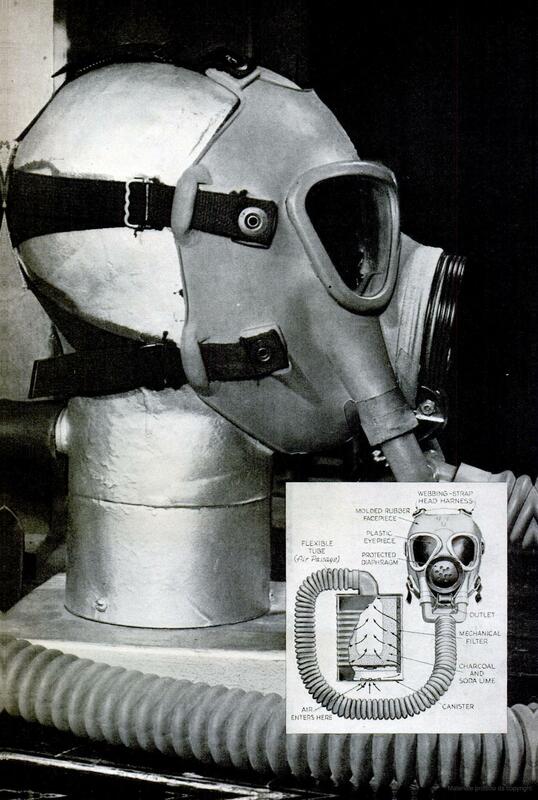

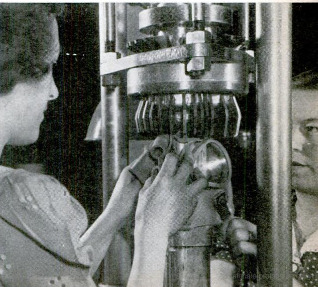

The Army service mask consists of three

principal parts: facepiece, canister, and

hose. The facepiece is died out of molded

rubber blank covered on the outside with a

thin layer of cotton fabric which is vulcan-

ized to the rubber. After cutting to exact

size, the blank is folded and the two short

edges are sewn together and taped with ad-

hesive tape, forming a gas-tight seam which

fits under the chin.

‘The eyepleces are made of shatterproof

glass held in the facepiece by detachable

screw-type retaining rims. The facepiece is

connected to the hose by means of an angle

tube made of die-cast aluminum which also

forms the seat for the rubber outlet valve.

Six elastic tapes (called the head harness)

hold the facepiece against the face with a

gas-tight fit.

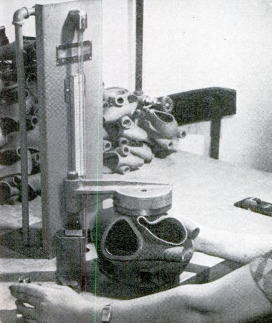

Army service masks were formerly made

in five sizes in order to fit any size or shape

of face. Recently, however, a new-type uni-

versal facepiece has been developed which

fits 95% of all sizes and shapes of faces. The

five percent of men who cannot be fitted with

a universal mask must still be furnished

with special sizes (about four percent with

small, and one percent with large sizes).

Even though it does not fit all faces, the

universal mask greatly simplifies the prob-

lem of manufacture, fitting, and supply in

the field.

The canister of the Army service mask is

a rectangular sheet-metal box which con-

tains the chemical filling and the mechanical

filter which remove toxic gas and smoke

from the inspired air. The chemical filling

comprises about

3/4 pound of an intimate mixture of 80 per-

cent activated charcoal and 20 percent soda

lime, which is composed of hydrated lime, ce-

ment, kieselguhr, sodium hydroxide, and wa-

ter. ‘The mechanical filter consists of a

cylindrical sleeve made of fibrous material

of such fine porosity that the solid particles

of toxic smoke are screened out of the air

passing through the material.

The inhaled air enters the canister

through a rubber disk inlet valve in the bot-

tom and is drawn first through the mechan-

ical filter where any solid or liquid particles

are screened out. The air then passes

through the chemical contents of the can-

ister where the toxic vapors are absorbed by

te charcoal or neutralized by the soda lime.

Gases which the charcoal does not hold firm-

ly by absorption (for example, phosgene)

are gradually released by it and are caught

by the soda lime, with which they enter into

chemical combination.

The hose which connects the canister to

the facepiece is a corrugated rubber tube

covered with cotton stockinette. The corru-

gations preserve flexibility and prevent the

tube from collapsing.

The carrier is a canvas satchel provided

with adjustable shoulder and waist straps

which permit it to be carried at the left side

under the arm, The opening at the front

permits the mask to be adjusted to the face

without changing the position of the carrier

as was necessary with our World War

masks.

Another recent improvement in the Army

service mask is the development of a sound-

transmitting diaphragm which is mounted

in a specially designed angle tube and per-

mits clearer transmission of oral commands

and telephone conversation. Diaphragm

masks may also be made with special eye

lenses adapted to fit observing instruments,

such as range finders and telescopes, and are

then known as optical masks. These are is-

sued only to soldiers having duties requir-

ing them to use optical instruments.

Recently developed in this country, the

so-called “training mask’ was designed for

the purpose of supplying the Army with a

cheap and lightweight gas mask for training

purposes. It differs from the standard Army

service mask, not only in design and con-

struction, but also in the process of manu-

facture which embodies many of the latest

innovations in gas-mask production. The

training mask is of the snout-type—that is,

the canister is attached directly to the face-

piece, thereby eliminating the hose tube. As

compared with the service mask, the train-

ing mask is lighter in weight, has a smaller

canister, and the facepiece is fully molded,

instead of fabricated, into final shape.

The facepiece of the training mask is of

universal size, with an integrally molded

air-supply tube and deflector. The eyepieces

of cellulose acetate are crimped on the face-

piece and are not round, as in the service

mask, but are specially shaped to afford

maximum vision. The facepiece fits closer

to the face and thus reduces to a minimum

the dead air space within the mask. The out-

let valve is of the circular disk type and

seats against a molded rubber seat within

the angle tube.

The canister is cylindrical in shape and

somewhat smaller than the standard service

canister. It, however, contains the same

kind of chemical contents and has a me-

chanical filter for removing toxic smoke.

Air enters through an inlet valve in the bot-

tom of the canister. Since the training can-

ister is smaller than the standard service

canister, it has a shorter life in gas concen-

trations and a higher breathing resistance.

It will, however, protect against all standard

chemical agents with a degree of protec-

tion equal to the standard canister.

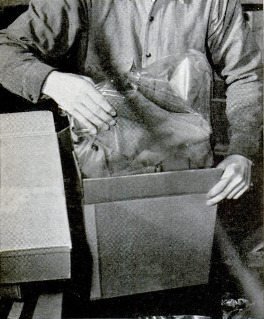

‘The carrier of the training mask is a

lightweight cloth bag with a single adjust-

able shoulder strap which is held against the

left side of the body by a cord passing

around the waist.

By molding the facepiece instead of fab-

ricating it, as in the standard service mask,

not only is the process of manufacture sim-

plified about 20 percent, but the number of

inspections for leaks and defects during the

process of manufacture is greatly reduced.

The latest type of gas mask developed in

this country by the Army is the so-called

noncombatant mask, which is intended pri-

marily for the protection of civilians whose

duties require them to remain in the thea-

ter of military operations where they may

be exposed to toxic gas. The noncombatant

mask is of the snout type with a facepiece

composed of laminated gasproof fabric, and

is equipped with the same six-strap elastic

head harness as the service mask.

The noncombatant mask is of the univer-

sal type and will fit practically all persons,

except babies and very small children who

require special types of masks. Although it

is not of the diaphragm variety, the reso-

nant quality of the facepiece fabric trans-

mits conversation to a considerable extent.

The canister of the noncombatant mask

is cylindrical like the training canister, but

is somewhat smaller and of lighter construc-

tion. It provides protection against all

known war gases in the same manner as

does the service mask but is not designed for

the long life and rugged use of the service

mask. The total number of hours it will

protect against high field concentrations of

gas is also less than with the service mask,

but since such concentrations cannot be

maintained for more than a few hours under

average conditions, the protection afforded

by the noncombatant canister is ample for

the purpose it is intended to serve.

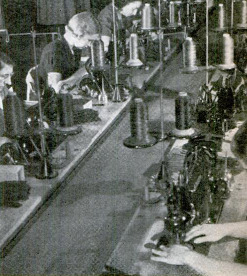

In time of peace, military masks are man-

ufactured in the United States only in Gov-

ernment arsenals. In time of war or na-

tional emergency, the production capacity

of the arsenals is far too small to meet the

demand and resort is had to supplementary

production by private industry, using dies

and patterns provided by the Army. For

this purpose certain commercial firms en-

gaged in similar lines of work are selected

to manufacture masks in time of peace, after

a survey is made of their facilities. When an

emergency arises, contracts are placed with

these firms on a cost-plus-fixed-fee basis.

Since the beginning of the present emer-

gency, several private companies have been

engaged in manufacturing gas masks in

whole or in part.

‘The cost of manufacturing gas masks

varies considerably depending principally

upon the type of mask. Thus the relative

costs of the several types of masks men-

tioned above are approximately as follows:

noncombatant mask, $3.00 apiece; training

mask, $4.00; service mask, $7.75; diaphragm

mask, $10.50; and optical mask, $10.00. The

cost of American gas masks is higher than

that of corresponding types of foreign

masks. This is due, not only to our higher

labor costs, but also to the superior con-

struction of our masks.

While the gas mask protects the respira-

tory organs and the face, it does not protect

the body against vesicant or blistering gases,

which readily penetrate ordinary clothing,

leather and even rubber and produce in-

capacitating burns. For full protection of the

body against vesicant gases special protec-

tive clothing is required. Such clothing con-

sists of a complete outer garment or suit of

oilskin with hood, and specially treated

heavy rubber gloves and boots. For civilians

a light oilskin cape with hood affords suffi-

cient protection until refuge can be taken

in gasproof shelters.

As masks and protective clothing are un-

comfortable and must be removed when eat-

ing, drinking, and sleeping, it is necessary

that additional means for protection against

gas be provided. Such a means is the gas-

proof shelter which is a refuge room made

air-tight and supplied with pure air through

a chemical filter. A slight plenum is main-

tained in the shelter so that the movement

of air is always from inside the room to the

outside. This insures against gas entering

the shelter from the outside atmosphere.

The air supply for the shelter is secured

by means of a rotary air pump, driven man-

ually or by electric motor, depending upon

its size. The air is drawn in from outside the

shelter through a chemical filter which is

constructed on the same principle as the

gas-mask canister. Gas shelters vary in size

from small family units for four or five

people to large public shelters accommo-

dating as many thousands.

Decontamination is the process of destroy-

ing toxic gases, especially vesicants such as

mustard, in order to clear materials, build-

ings, or areas that have become dangerous

to life by contamination with toxic gas. The

principle of decontamination is simple and

consists essentially in applying a gas-neu-

tralizing agent to all contaminated surfaces

as soon as possible after contamination.

In actual practice, decontamination is at-

tended with many practical difficulties ow-

ing to the insidious and dangerous character

of vesicants and the effort and skill required

to determine the exact areas to be treated

and the great care necessary to insure that

all traces of gas have been removed.

Ihe best all-around agent for chemically

neutralizing vesicants is ordinary bleaching

powder (chloride of lime). This material

reacts vigorously with vesicants and con-

verts them into harmless compounds. The

bleach may be applied in the form of dry

powder, mixed with earth or sand to pre-

vent combustion, or in the form of a paste

or liquid solution in water.

In liquid form the bleach may be sprayed

with an ordinary spraying apparatus. A

mobile sprayer for decontamination work

consists of a 20-gallon tank fitted with a

hand pump and two spray nozzles, each with

fifteen feet of hose.

The protective measures which we have

mentioned are but a small part of the to-

tal effort required to prepare for adequate

chemical defense. When all its many rami-

fications are considered, chemical defense is

indeed a formidable problem, but one which

must, nevertheless, be solved if we are to

escape the disasters due to gas of the last

war but on a vastly larger scale. In fact, the

best insurance against employment of chem-

ical agents by an enemy is the knowledge

that our country is fully prepared to defend

itself against the use of all types of chemi-

cal agents, and our Army is ready to retali-

ate promptly if they are used against us.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Lieut. Col. A. M. Prentiss (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

100-104,212-215

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941