-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Defense has the right of way on automotive production lines

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Defense has the right of way on automotive production lines

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE Detroit genius for industrial or-

ganization is sorting out the sudden

chaotic avalanche of defense orders

with its customary frantic and incredible

orderliness. It is responding to the fabulous

impetus of something like a billion and a

half in armament orders assigned by the

U.S. Government to the automobile industry.

The vast industrial center, already a huge

magnet, drawing raw materials and manu-

factured parts selectively from many parts

of the country, is being called upon suddenly

for all its reserve power. Its standard

products, such as automobiles, trucks, and

their accessories, were in extraordinary de-

mand, but now there are imperative pleas

also for airplane, marine, and tank

engines; for the airplanes and the

tanks themselves and for antiair-

craft guns, cook stoves, ammuni-

tion components, refrigerators,

Diesel engines, and a conglomera-

tion of other articles.

Mass production in all lines was

the demand. It would seem to be

enough to strike any group of in-

dustrial engineers dizzy. Dizziness

is more or less a normal state, how-

ever, for an industry accustomed

to redesigning its major

output every year, and the

Detroit industrialists

proved themselves tops.

They turned out to be

steadiest when spinning

madly.

There were factories to

be built whose individual

dimensions are reckoned

in fractions of a mile. The

grandparents and the

great-uncles of the ma-

chines which were to turn

out the new products had

to be found or manu-

factured in widely sepa-

rated parts of the country,

assembled and put to work

s0 that their grandchildren

and grandnephews and

nieces would be ready for

installation when the

factories were completed.

There were materials to

be ordered in stated

quantities for delivery at

set dates so that the vast jig-saw puzzle

would fall progressively into place and

when the final rivet and the last nail was

driven in Detroit, machines and materials

would come marching into each building.

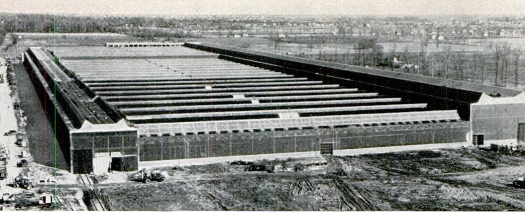

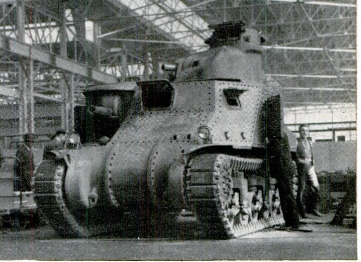

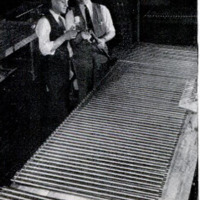

Between last summer and this summer

fourteen acres of farmland sprouted the

gigantic mushroom of the Chrysler tank

arsenal, a vast structure of steel, glass,

and brick which is a trifle more than a

quarter of a mile from wall to wall. At-

mospheric haze dulls the vision of the spec-

tator seeking the details of the farther end.

Freight trains enter the building at one

side and unload at the head of sub-assembly

lines which stretch like the bars of a

gridiron crossways of the plant. Huge

grotesque machines with arms and angles

reminiscent of Rube Goldberg or a non-

objective painter stand in ranks beside the

sub-assembly lines, which terminate in

three assembly lines on the far side of the

building where the tanks take form, five

of them in each eight-hour shift.

Another spectacular achievement was the

Ford defense plant, literally a hothouse

growth. Work on it Was started September

17, 1940, Detroit winters forbid masonry

construction, but Detroit genius was not to

be balked. An engineer who had encountered

a similar dificulty on an assignment in

northern Russia inclosed the entire job in

a shelter of fiber board and tar paper and

installed steam heat. Twelve hundred men

worked three shifts a day in it and by

April the first of 4,236 Pratt & Whitney

twin-row, radial, air-cooled engines were

coming off the assembly lines. Now the

1,750 and 2,000-horsepower en-

gines are taking to the air.

Similar miracles were wrought

by Packard, Studebaker, Hud-

son, General Motors, and other

industrial wizards. Minor mira-

cles were being performed all

over the country by the makers

of machine tools whose powers

had been invoked by Detroit.

That industry had doubled in

size in a year, constructing for

its own use more machines than

it had turned out in any of the

years between 1931 and 1934.

The Detroit manufacturers al-

ways have been in the market

for completed parts and knew

the necessity of scheduling such

orders in advance. Every year

Buick buys 2,200 separate pro-

duction items and General Mo-

tors has 20,000 industrial and

supply firms on its list of sub-

manufacturers. The purchasing

and associated engineering staffs

always have maintained the

closest relations with these

sources of supply and hundreds

of their members were assigned

at once to the job of stepping up

and broadening production. They

have kept to their schedule.

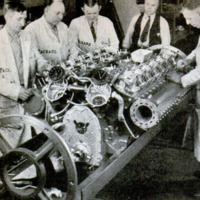

General Motors’ Allison Di-

vision, currently making more

than 400 12-cylinder, liquid-

cooled, 1,000-horsepower plane

motors a month in its defense-

built Indianapolis plant, and an-

ticipating 1,000 a month by De-

cember, put into effect a vast

“farming-out” program to

achieve this goal. Its purchas-

ing agents distributed major

sub-orders to plants in 65

communities, which in turn

buy from hundreds of other

firms.

Studebaker, with a $33,

600,000 order for Wright

Cyclone 1,700-horsepower

air-cooled radial engines,

sublet 60 percent of the

work to other firms, keep-

ing 40 percent to be han-

dled in its three new defense

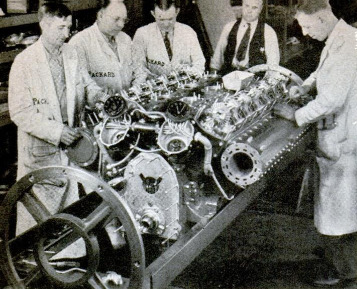

plants. Packard, almost

ready to start production

of 9,000 Rolls-Royce 1,000-

horsepower plane engines—

6,000 of them for England—

in new buildings valued at

$35,000,000, is depending

upon 70 suppliers for parts

and materials. Chrysler's

tank arsenal will draw up-

on the products of 117 com-

panies.

It is one of the basic wis-

doms of Detroit's know-

how. Even Ford, which

boasts the closest thing to

a self-contained industrial

plant at its gigantic Rouge

works, calls upon many out-

side parts suppliers and,

like General Motors, buys

from every state in the

country. The British only

recently adopted the idea

with their “bits-and-pieces’

program, but not before

several too-highly central-

ized plants had been blasted

by aerial bombs.

Germany was more provi-

dent. As’ early as 1987,

sealed crates said to con-

tain machinery for making

toys after a few easy les-

sons were distributed to

German farmers, who were

told to store them for fu.

ture use. With the invasion

of Poland, Nazi officials ap-

peared and ordered the crates unpacked.

Out came drill presses, automatic screw-

cutting machines, small drop forges, and

similar machine tools with which the farm-

ers, after their easy lessons, were soon mak-

ing airplane fittings, bomb doors, and other

parts for Messerschmitts and Heinkels and

Junkers. That was farming out, Nazi style.

A recent estimate showed that the auto-

mobile companies have shouldered a total

of $737,900,000 worth of plane-engine con-

tracts for this country and Britain, nearly

a fifth of all on order. Allison's order is for

$234,000,000, Packard's for $217,000,000,

Ford's for $122,000,000 and Buick’s for

$91,000,000 for the Pratt & Whitneys. Con-

tinental Motors’ is for $40,000,000 for

‘Wright 400-horsepower Whirlwinds con-

verted for use in tanks, and Studebaker’ for

$33,600,000 for the Wright Cyclones. Any

or all of these orders may be vastly in-

creased before you read this.

Two major plane builders, Martin and

Consolidated, placed their Government-se-

lected bombers on display in an empty De-

troit plant, where 1,400 manufacturers from

all over the country studied them.

Most reported that they could sup-

ply some of the parts.

As a result, Chrysler was given

orders for the two forward sec-

tions of the twin-engine Martin

B-26 fuselage, which it is building

in the Graham-Paige plant. Hud-

son is making the rear section and

small parts. Goodyear, pending

plant construction, is making the

‘wings in its gigantic “air dock” at

Akron, where a special ceiling had

to be bullt to prevent condensed

moisture from “raining” on the

work.

General Motors’ Fisher Body

Company is expanding its Mem-

‘phis, Tenn, plant for construction

of the North American-designed

B-25 bomber, a type similar to the

Martin. Ford is rushing an $11.-

000,000 factory near Ypsilanti,

Mich, for complete four-motor

Consolidated B-24 bomber air-

frames.

Detroit reaches down into its bag

of tricks and comes up with new

wonders like the Allison airoraft

and Packard marine engines. An-

other engine tapped for defense

duty and as adaptable is the prod-

et of the Cleveland Diesel Engine

Division of General Motors. Ac-

tually, it is not so much an engine

as it Is two cylinders. One is com-

paratively small, with only 71 cu-

bic inches displacement. The other

is large—567 cublc inches. Just

these two are made by the com-

pany. Yet they are the power

packages for engines ranging in

horsepower from 15 up to 1,600,

and they can power anything from

‘portable lighting plants to the big-

gest. submarines.

Uncle Sam has ordered Diesels using these

cylinders to the tune of $140,000,000, princi-

pally for the Navy. The engines are about

one quarter the size and weight of the Die-

sels that powered American submarines in

the First World War. They more than dou-

ble the cruising range of the earlier subma-

rines, and their weight, space, and fuel econ-

‘omies step up the value of Navy tugs, patrol

boats, fuel transports, and other vessels.

Many believe that these amazing two-cycle,

relatively high-speed Diesels—installed in

large numbers in a single hull will power

& radical new American battleship.

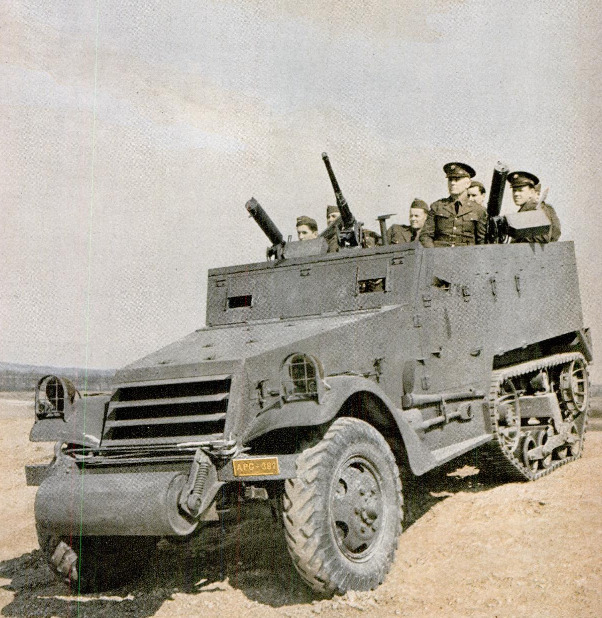

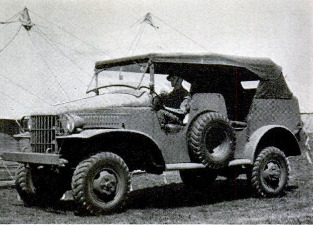

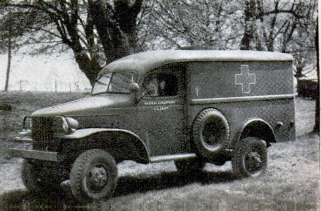

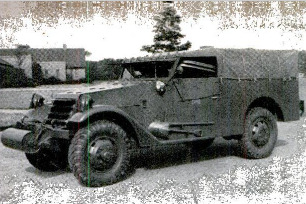

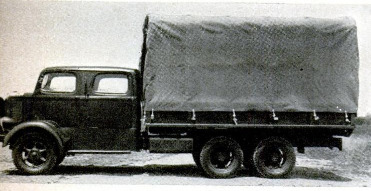

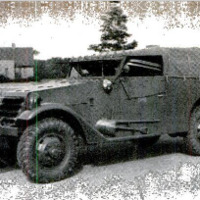

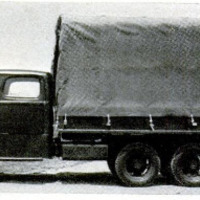

Some 13,000 military vehicles a month

are being built by the automobile industry,

with 195,000 already delivered and 60,000

others scheduled for early delivery.

In addition to 5,900 passenger cars and

27,000 motor cycles, the vehices ordered are

4500 quarter-ton scout cars from Ford,

‘Bantam, and Willys; 69,000 half-ton pick-up.

and reconnaissance trucks from White; six-

ton and heavier units, from Autocar, Bied-

erman, Chevrolet, Corbitt, Diamond-T,

Dodge, Federal, GM.C., International-Har-

vester, Mack, * Marmon-Herrington, Reo,

Sterling, and Walters. Practically ail mill:

tary trucks are four-wheel drive, many are

six, and others are half-track. The total

does not include 37.800 trailers for 2}4-ton

trucks, being built by Nash.

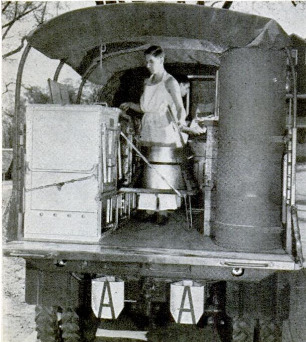

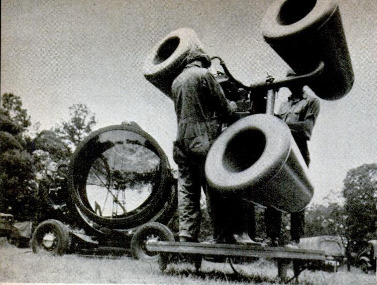

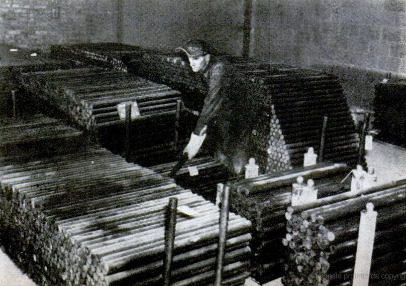

And the defense articles of Detroit stretch

on and on: gun and torpedo parts for the

Navy, bomb and shell components, eld

Kitchens, field range cabinets, antiaircraft

fire-control apparatus, instruments, aviation

spark plugs, radio parts. For many of

these, the industry's parts and equipment

makers account. Typical are the Briggs,

Fisher, and Murray car-body builders, the

huge wheel and brake-drum makers such as

Kelsey-Hayes Wheel, Budd Wheel, and Mo-

tor Wheel, and the Bendix Products Division

of Bendix Aviation.

The War Department ia watching with an

eye to the future the Detroit research lab-

oratories. Most startling appears to be the |

simultaneous development in each of the |

Big Three laboratories of new airplane |

engines to develop from 1,500 to 2,400 horse-

power. All three projected engines aro |

liquid-cooled, in-line types. Fords is a 13- |

cylinder, V-type power piant with an ex- |

haust-driven supercharger, and fuel injec |

tors Instead of carburetors. In construction, |

the cylinder liners, crankshaft, and other

major parts will be made by a new “centrif- |

ugal-casting” method which Ia claimed to |

be faster, cheaper, and to produce stronger |

parts thin conventional forging and ma-

chining methods now employed.

Chrysler and General Motors are moro |

secretive. Reports are current, however, |

that Chrysler's engine will make better |

mechanical use of extremely high-octane |

fuel than any engine yet devised. The GM. |

design 1s a conversion of the Allison, using |

four banks of cylinders arranged in a W |

instead of two in a V as at present.

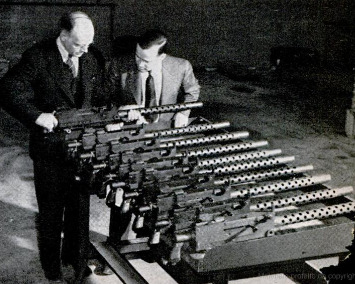

Engineers in one General Motors plant

designed a multiple drill that bores out six |

‘machine-gun barrels at once—a feat mot |

even the old-line gun makers bad accom- |

plished. A Chrysler research group de- |

signed a new plane landing gear which |

could be bullt faster than present types. |

‘The list of defense orders placed with the |

industry looks like a dozen pages from your

telephone book, and the cost figures mean |

about aa much. Because new contracts are |

coming in so fast, totaling their value ls

next to impossible, Some recent official

figures out of Washington put the indus |

trys defense contracts at $1,076,082,000, but |

it is estimated that they are by now above |

the billion-and-a-half mark, with no end In |

sight. That's a lot of money to pay even |

for Detroit's know-how. Yet no one bas |

complained but Detroit, where the only |

thing they'd rather do Ia build new and |

Detter automobiles. |

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Schuyler Van Duyne (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

113-121

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 2, 1941

Screenshot_1.png

Screenshot_1.png Screenshot_2.png

Screenshot_2.png Screenshot_3.png

Screenshot_3.png Screenshot_4.png

Screenshot_4.png Screenshot_5.png

Screenshot_5.png Screenshot_6.png

Screenshot_6.png Screenshot_7.png

Screenshot_7.png Screenshot_8.png

Screenshot_8.png Screenshot_9.png

Screenshot_9.png Screenshot_10.png

Screenshot_10.png Screenshot_11.png

Screenshot_11.png Screenshot_12.png

Screenshot_12.png Screenshot_13.png

Screenshot_13.png Screenshot_14.png

Screenshot_14.png Screenshot_15.png

Screenshot_15.png Screenshot_16.png

Screenshot_16.png Screenshot_17.png

Screenshot_17.png Screenshot_18.png

Screenshot_18.png Screenshot_19.png

Screenshot_19.png Screenshot_20.png

Screenshot_20.png Screenshot_21.png

Screenshot_21.png Screenshot_22.png

Screenshot_22.png Screenshot_23.png

Screenshot_23.png Screenshot_24.png

Screenshot_24.png Screenshot_25.png

Screenshot_25.png Screenshot_26.png

Screenshot_26.png Screenshot_27.png

Screenshot_27.png