-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Fighter pilots try new wings

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Fighter pilots try new wings

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

AIRMEN of America's fighting forces are

learning to use a new kind of wings.

Convinced by demonstrations on European

battlefields that motorless aircraft can't be

overlooked as military weapons, useful for

invasion or other purposes, both the Army

and the Navy are now experimenting with

gliders.

Recent orders assigning Army men to this

work were unprecedented. as heretofore the

Air Corps has looked with disdain on motor-

less fiying for its pilots. Air Corps officers

have been assigned as observers at soaring

contests of The Soaring Society of America,

at Elmira, N.Y., to be sure, and individu#

officers have attended soaring meets out of

purely personal interest. But the official

Air Corps attitude has been distinctly cold

toward the use of gliders for any purposes.

The Navy's entry into this field, isn't so

radical a turn-about in attitude as that of the

Army, for in 1934-1935 it did officially carry out

experiments with motorless craft at Pensacola.

However, those experiments were restricted to

an investigation of the value of training of student

pilots and had nothing to do with the employment

of gliders as an invasion vehicle.

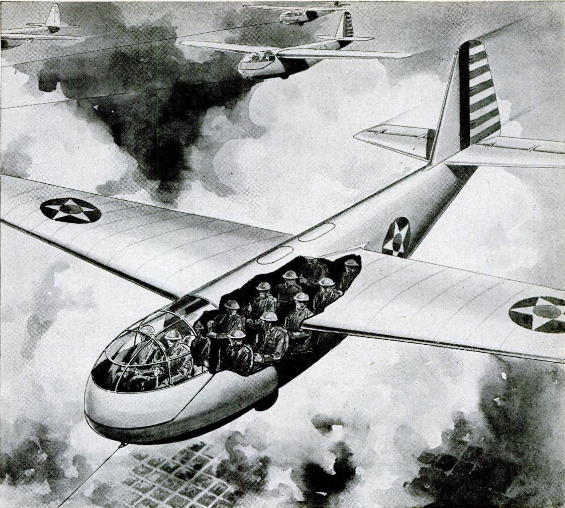

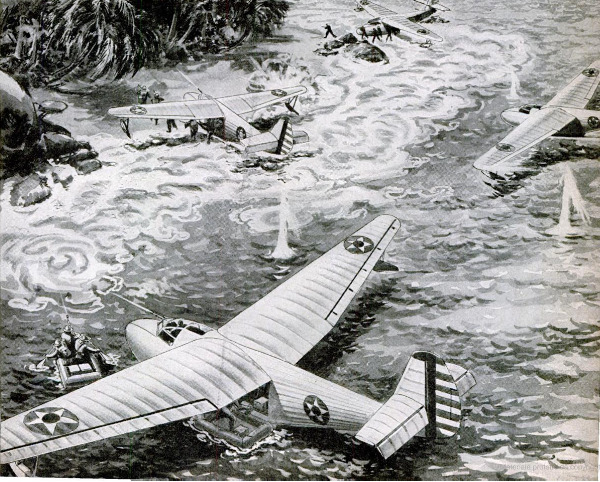

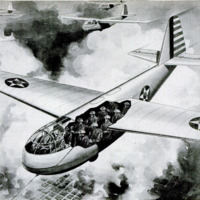

At present, the Navy is working on two designs

for troop or cargo-carrying gliders, according

to recent testimony given the House Naval

Affairs Committee by Commander Ralph S.

Barnaby, the Navy's expert on motorless

flying and president of the Soaring Society

of America. One of these would be capable

of water landings. This is most logical inas-

much as the Navy's Marine Corps has long.

Deen a specialist in the art of landing troops

under fire.

Design and piloting of troop - carrying

gliders, which the Army is also working on,

present no special problems, either. Such

matters are governed mainly by the power

and stalling speed of the tow plane. The

latter is important because the gliders con-

stitute quite a drag and the tow plane must

be flown as slowly as the aerodynamic char-

acteristics of the gliders require. Any air-

plane pilot can fly motorless craft after a

few hours spent becoming familiar with the

“feel” of the glider and its behavior charac-

teristics, which is the usual procedure in

making the transition from one type or

weight of airplane to another.

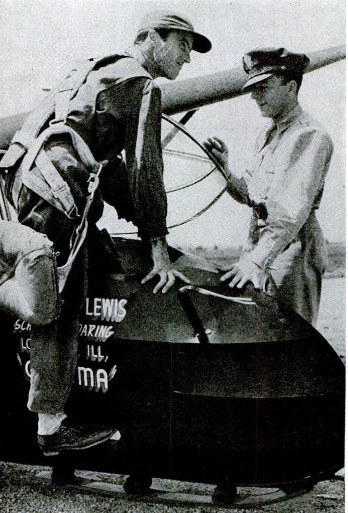

The first Army Air Corps order provided

that six pilots take a course spread over

three weeks at the Warren E. Eaton Motor-

less Flight Facility at Elmira, N.Y, and

that another six do the same at the Frank-

fort-Lewls School of Soaring, at Lockport,

TIL. These courses call for a minimum of

25 hours of soaring and 10 hours of piloting

towed gliders. Both schools opened for

civilian motorless-flight training this spring.

The first phase consists of tows at a few

feet altitude, the towing being supplied by

automobile or winch, to become familiar

with the craft. Utility gliders of the Frank-

lin type are used in the early phases because

they are rugged enough to stand up under

practice landings and take-offs, efficient

enough aerodynamically to permit fairly

extensive soaring. The pilots graduated to

sailplanes in the later phases. Particularly

useful in learning to master sailplanes are

the two-place, metal-structure Schweizers

‘manufactured in Elmira. About 22 hours of

motorless flying was called for with land-

ings by tow car or winch. The balance of

the 30 hours was to be spent in single and

multiple tows behind powered planes. Alto-

gether they put in 10 to 14 hours per day on

both ground and flight work.

It should be remembered in all discussions

of motorless flying that there are two types

—gliding, which is merely sliding downhill

in the air after the craft has been cut loose

from tow-car, winch or airplane, and soar-

ing, which means gaining altitude by means

of vertical currents.

All utilities can soar. Even the heaviest

powered airplanes are boosted upward on

occasion. For most efficient soaring (or

airsailing) we have the sailplane with its

high aspect ration wing. The military would

be primarily interested, of course, in gliders

that can glide long distances after they have

been cut loose. The gliding ratio of a glider

is about 14 feet in the horizontal plane to

one vertically, while sailplanes have a

gliding ratio of about 20 to one.

The Army pilots experienced no trouble in

making the transition from the high-pow-

ered, heavy Air Corps planes to which they

were accustomed to the motorless craft.

They readily won the Federation Aeronau-

tique International “C License,” which is

the international license (issued in this

country through the Soaring Society acting

for the National Aeronautic Association) in

recognition of achievement of a basic soar-

ing flight. To qualify a pilot must fly his

ship above the point of release for at least

five minutes before official observers.

On one solo flight Major Frederick R.

Dent, assistant chief of the Materiel Divi-

sion at Wright Field, and in charge of the

research project at Elmira, climbed from

point of release at 1500 feet to 4,000 feet

above the valley of the Chemung River fac-

ing the Eaton soaring site at Elmira. That

he at least among the Army men had been

impressed by the potentialities of soaring

as an advanced training procedure is evi-

denced by his statement that “Any power

pilot can increase his proficiency by glider

flying.”

The seriousness with which the Army is

taking this research program is indicated

by Major Dent's regular position at Wright

Field. The other pilots were detached from

duty at the Middletown, Pa., and Fairfield,

Ohio, Air Corps depots, and other posts.

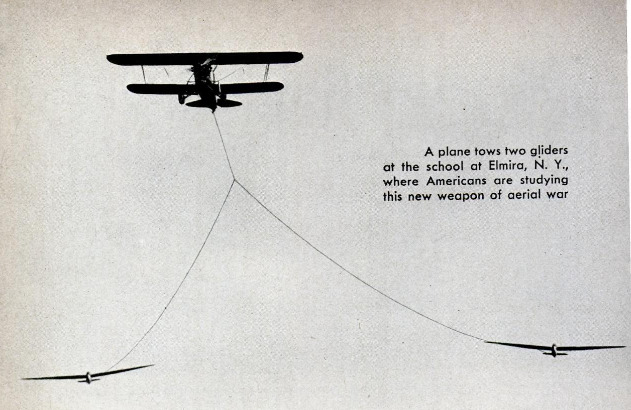

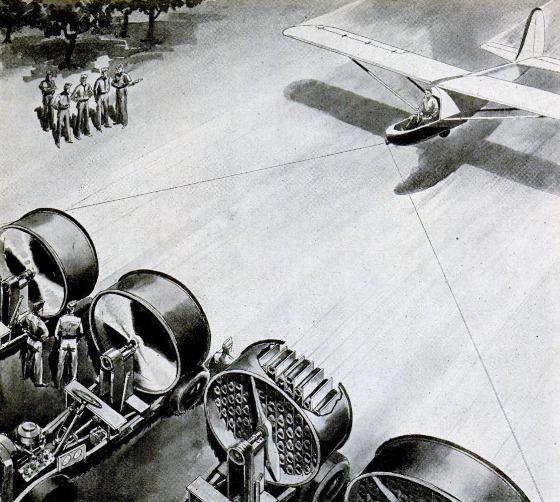

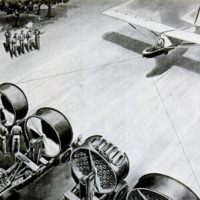

A multiple-tow take-off is done as fol-

lows: The tow plane is stationed as far

down the runway as is necessary to spread

the motorless craft behind it. They are

placed on the ground in the same position

they will occupy in the air. The formation

may be tandem, one ship behind the other

with a rope lining each unit, or fanned out,

with an individual rope between each unit

and the tow plane. The length of the rope

between the plane and the first glider in

the usual V formation of three gliders is

300 to 500 feet. A wire or & %-inch stranded

rope is used.

On signal the airplane pilot moves the

throttle ahead gradually. As each glider

gains flying speed, which of course they

reach before the airplane gets up flying

speed, it takes off and then is held close to

the ground until the airplane is in the air.

From then on the gliders keep slightly above

the tow plane and in regular step formation,

the pilots being careful not to vary much

from this position lest the drag be seriously

increased or the plane made unmanageable

Dy exerting downward, sideward, or upward

pulls. Each glider pilot can release from

the tow plane as desired and the tow-plane

pilot can cut loose from his charges behind.

Usually there is an automatic release in

case an excessive pull is exerted. A Waco

and a Stearman served as the “aerial tugs”

at Elmira.

There has been much talk about the great

reservoir of glider pilots possessed by Ger-

many, and the idea that we should have a

similar pilot backlog. It is a fact that some-

thing like 100,000 motorless-flight pilots

were trained there but they were glider-

trained simply because under the Versailles

Treaty Germany was allowed or could af

ford only the motorless types of craft.

We in this country have a much better

backlog. With something like 100,000 civil-

ian airplane pilots (including students) we

have a group that could become excellent

glider pilots through only short transition

periods. And new pilots can be brought

along faster than was ever possible in Ger-

many through glider flying alone, because

learning to handle the controls of an air-

craft, which is the primary phase of flight

instruction, can be learned quicker and more

positively on our thousands of powered civil

aircraft. This country's great fleet of light-

planes thus constitutes one of our greatest

assets, militarily as well as in a civil sense.

We also have a corps of experienced soar-

ing pilots for instruction and supervision

purposes. The 144 glider pilots certified by

the CAA as of June 1 seems to constitute

a small group. But of that number 58 held

commercial certificates, which means that

they are authorized to give instruction, and

many others of the 144 could be given fur-

ther training to qualify. In addition there

are several hundred persons who have had

much experience in all phases of motorless

flight over many years who are available

to assure plenty of competent leaders to put

whatever program might be selected on a

sound basis.

Where the Army and Navy will go from

here is anybody's guess at the moment. Both

services have emphasized strongly that their

present work is highly experimental. Per-

haps, however, by the time this appears at

least a substantially expanded research pro-

gram will have been launched, or possibly

the services will have plunged into the de-

velopment of fully organized glider transport

corps. In any case, the soaring movement

stands ready to do its part, and without

doubt one of the most radical innovations

in our military history is in the making.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-09

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

60-65

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 3, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 3, 1941