-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

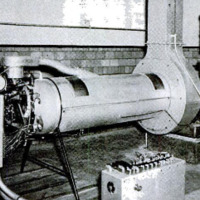

Housing a hurricane: soundproof laboratory built to test airplane motors

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Housing a hurricane: soundproof laboratory built to test airplane motors

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

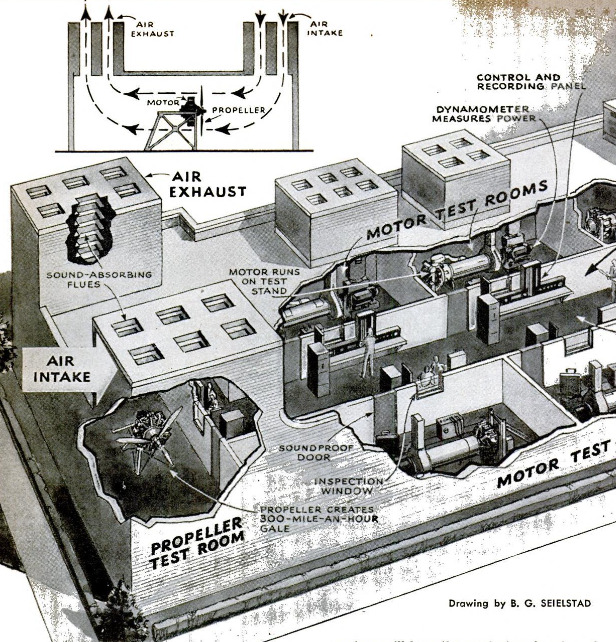

NOISES too loud for their full blast to

be heard will fill soundproof rooms,

when aviation engines of up to 2,000

horsepower go into action, in the University

of Kentucky's new motor and propeller test-

ing laboratory at Lexington. Acoustic ex-

perts rate the combined roar of such a pow-

er plant and the shriek of its propeller at

upwards of 150 decibels, or sound units. Hu-

‘man ears respond only to about 120 decibels;

above that crescendo of pandemonium, they

distinguish nothing louder.

Sounds of such intensity, 1,000,000 times

greater than those of a busy street corner,

not only are nerve-racking but actually dan-

gerous to health. A man without ear plugs,

entering a room where an air motor is run-

ning under full throttle and heavy load,

would suffer temporary deafness at least. |

Even with ears protected, many persons

would be affected with nausea.

For this reason, workers go into the five |

motor test rooms, and the propeller-testing

section at the end of the laboratory, only to

make preliminary adjustments. Then, clos-

ing soundproof doors, they withdraw to a |

central observation room from which the

ignition, throttle, and spark advance of each

motor may be operated by remote control.

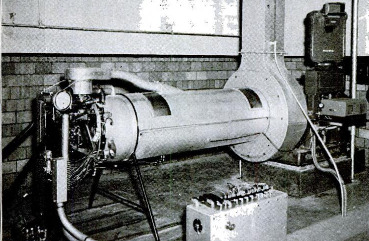

While engines pit their strength against

measuring devices called dynamometers—in

principle nothing more than giant brakes—

observers look on through thick windows

and read dials and gauges. Manometers

give pressure readings, electric thermom-

eters show the temperature at 28 different |

points on an engine wader test, a tachometer |

Indicates revolutions per min-

ute, and a gasoline meter

checks fuel consumption, giv-

ing a thorough picture of the

motor’s performance under

widely variable operating

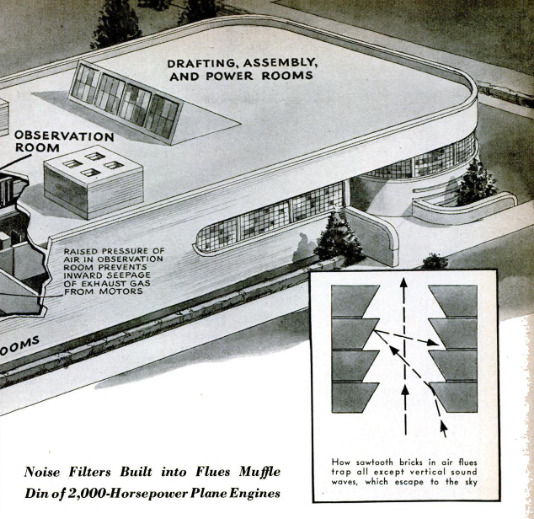

conditions. Lest poisonous

exhaust gas seep into the ob-

servation gallery, its ventilat-

ing system maintains a slight

ly higher air pressure than in

the surrounding test rooms.

Through the propeller-test-

ing section, during a trial,

rushes an artificial hurricane

of 300-mile-an-hour speed.

Drawing in and discharging

a volume of 2,500,000 cubic

feet of air a minute, while

straining out noises that

would shatter the academic

calm of the campus and be-

devil residents in the neigh-

borhood, presented a major

problem. Sound engineers

solved it in a remarkable way.

Incoming and outgoing air

streams both pass through

multiple flues in towers atop

the building. Sawtooth bricks

of sound-absorbing material

line the flues. Angles of the

brick ends have been so clev-

erly calculated that a sound

wave echoing from one will

be sure to strike another, and

another, until its force dies

out within the flue. The action might be

compared to that of a billiard ball losing

some of its momentum each time it caroms

off a rail of the table, and finally coming

to rest.

Only sound waves that enter the flues in

an absolutely vertical direction can escape,

and these travel upward to great altitudes

and dissipate themselves in the sky. Once

in a while, it is true, peculiar atmospheric

conditions may give the upper air the sound-

reflecting quality of a whispering gallery.

Then people as far as 12 miles from the lab-

oratory will hear the mysterious buzzing of

“ghost” airplanes apparently coming from

overhead.

Rooms for dratting, assembling, lockers,

tools, and a self-contained power plant

complete the ultramodern laboratory. Huge

underground storage tanks outside the

building feed fuel to the greedy motors—a

1,000-horsepower motor consumes 100 gal-

lons of gasoline in an hour. City water, of

all things, supplies the needed pressure. The

gasoline floats on top of water admitted

through mains to the bottom of the tanks,

since it is lighter, and is thus forced into a

fuel pipeline system running through the

laboratory. An automatic regulating device

controls the flow of water from the mains,

with the result that fuel is fed from the

tanks at uniform pressure.

The establishment, it has been announced,

will take a direct part in national defense

by serving as a power-plant branch for the

U. S. Army Air Corps’ program of training

and research. Hand-picked engineers will

go there to receive a 12-weeks course in lab-

oratory technique and methods.

In addition to the testing and studying

of actual production-model airplane engines,

the laboratory will be used for conducting

researches with experimental one-cylinder

engines to help solve new problems in com-

bustion, lubrication, cooling, and mechanism.

With the great increase in plane production,

the importance of research is obvious.

Directing the work of the laboratory is

A. J. Meyer, who was superintendent of the

Fokker Aircraft Company at Amsterdam,

Holland, 20 years ago and more recently has

served as research engineer for several lead-

ing American aeronautical corporations. He

holds more than 125 patents on engine de-

sign and construction.

Called the Wenner-Gren Aeronautical

Laboratory, the testing plant takes its name

from the noted Swedish industrialist whose

grants made it possible. It is not the first

time that Axel L. Wenner-Gren has made

news. At the outset of the war, he saved

350 lives when he brought his yacht, the

Southern Cross, to the rescue of passengers

aboard the sinking British liner Athenia.

More recently, he sponsored an expedition

that discovered lost cities of the Incas in

uncharted wilds of Peru. Now, in the Uni-

versity of Kentucky laboratory, he has

found a way to benefit science and the armed

forces of democracy.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Walter Brehm (article writer)

B. G. Seielstad (Illustrator)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-09

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

73-75

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 3, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 3, 1941