Dogs of War

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

Dogs of War

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Dogs of War

-

extracted text

-

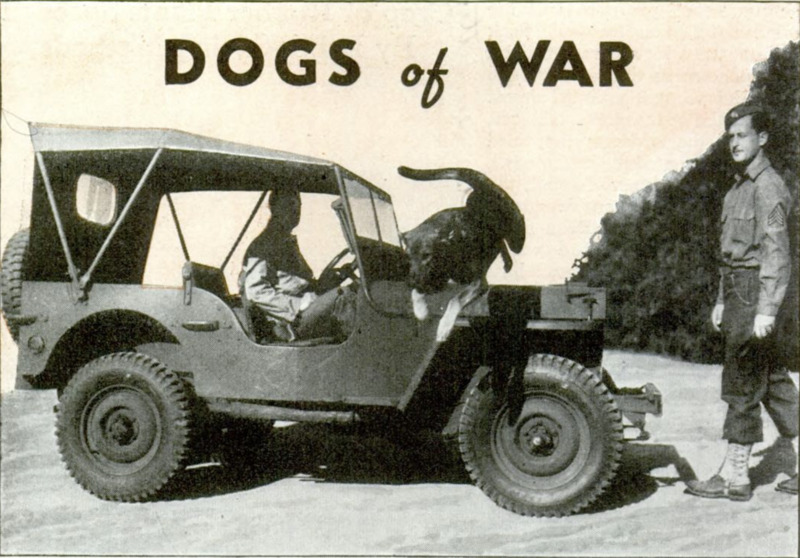

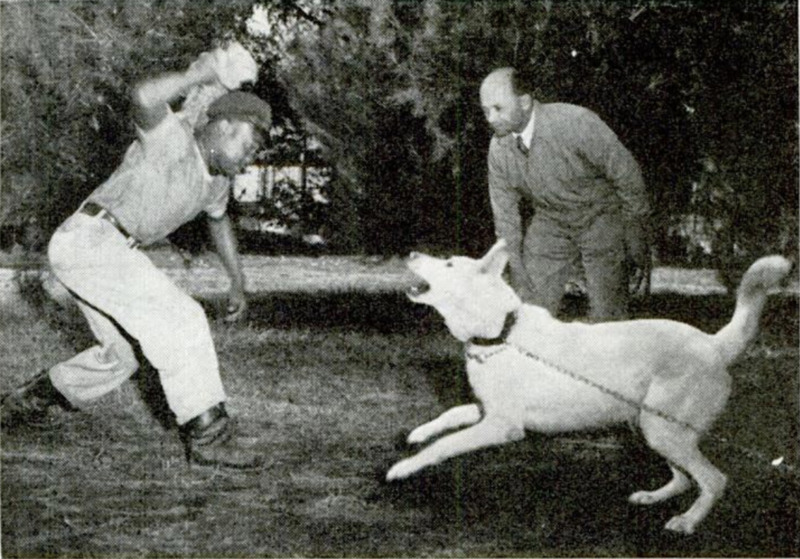

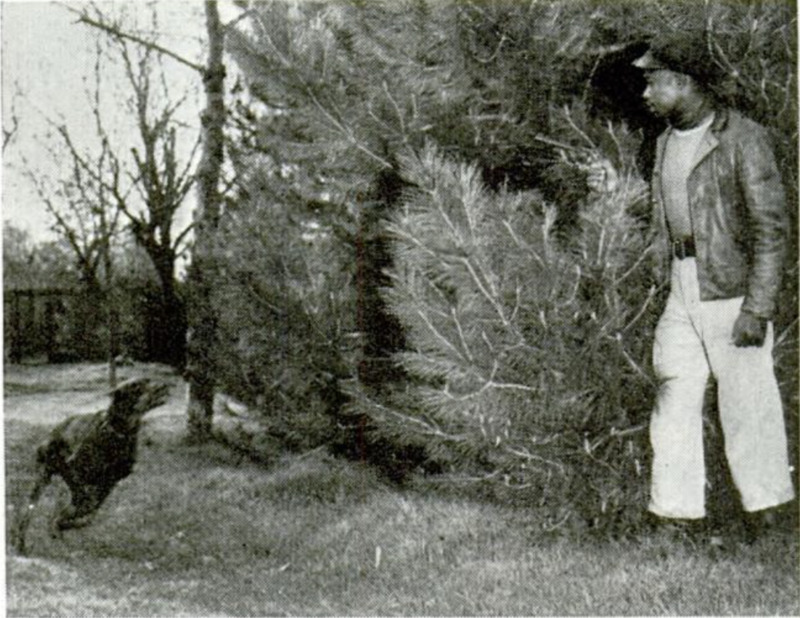

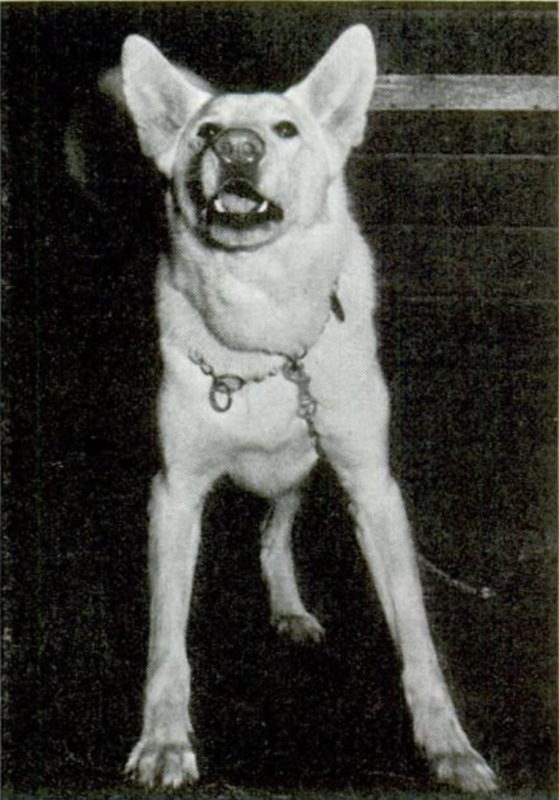

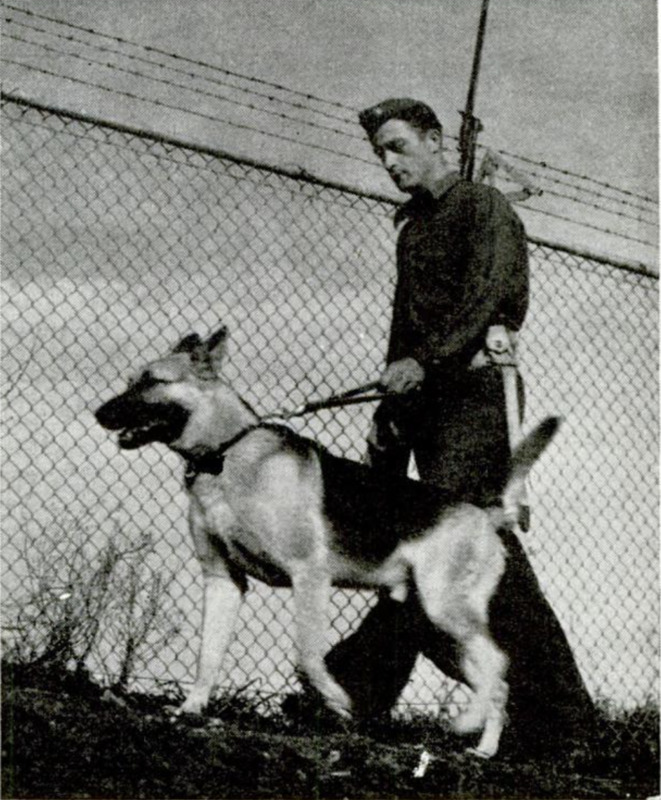

WAR dogs of the United States Army are distinguishing themselves for bravery in the line of duty. Recently a soldier and his dog companion were walking beat on night patrol against spies and saboteurs. All was well, as far as the sentry knew, but the dog’s keen nose detected someone lurking in the brush. At the first growl the soldier challenged the unseen prowler. There was no answer. At once the sentry gave the sharp command “Get him!” The dog leaped forward with a snarl and an instant later there was the sound of an impact and a cry of pain. The man was captured. One soldier and a dog are better than two men for guard duty and for extended sentry duty in the field. The four-legged sentry smells and senses danger that the human can’t see or hear. There is no chance now for the soldier on night patrol to be attacked by surprise or ambush. His dog is a “one shot” weapon far better than a rifle in the dark. At Fort MacArthur near Los Angeles the Army is using dog sentries in an operation that started as an experiment and that has turned out to be a success. Several dozen dogs go out on military duty each night. Some of them guard enclosures by themselves and give the alarm if anyone approaches, while others march with regular sentries. Ordinarily a dog obeys one master best, but at Fort MacArthur the desire has been to produce trained dogs that will work equally well with any soldier. Under the direction of Lieut. Col. Glen Miller, a training course was worked out by Sergeant Robert H. Pearce that teaches the dogs to operate anywhere at any time and under the command of any soldier who is in charge of them. Savage fighters when the need arises, they are easy to control. They are trained to attack anyone who approaches a sentry and yet each permits himself to be handed over quietly to the sentry’s relief when the guard is changed. Dogs work with different men each night. High intelligence and a combative spirit are two of the canine enlistment requirements. And an Army dog must be able to knock a man down. Even a 200-pound man can be knocked sprawling by a dog that weighs only a quarter as much but that has learned to make a tremendous lunge and to hit high. Most of the canine recruits were household pets in civil life and are friendly with each other at the start. But each becomes extremely jealous of the other dogs as training proceeds. The Army has a waiting list of nearly 1,000 dogs whose owners have volunteered them for the service. You can teach an old dog new tricks, fortunately, and Sergeant Pearce picks dogs thathave outgrown the playful puppy stage. The training methods that he has developed are simpler than most and result in rapid and thorough training even for dogs that are five or six years old. First on the program are several weeks of standard obedience instruction. Pearce and several other trainers all work with each dog. This helps the dog to understand that he is to obey anyone who takes charge of him. Next the dogs work out on a stuffed dummy hung several feet off the ground. They have to leap at the dummy to reach it and this teaches them to attack high. Then a volunteer dressed in several old overcoats and with his arms and hands bandaged with padding engages each dog. The man fights always with his right hand to teach the dog always to go after that arm. Finally comes the conditioning that trains the dog to regard every stranger with suspicion after dark. This part of the training, naturally, is carried on at night, and consists of startling the dog by having some of the trainers leap at him who lorks from behind bushes or from around corners. Alarmed by such an attack, the dog fights back savagely. This puts him constantly on the alert against surprise. When a dog graduates from training school Sergeant Pearce stamps his name on a regular identification tag that reads “U. S. Army Dog Sentry” and attaches it to the dog’s collar. The dogs work 12 hours a night with one night a week off. They get a meal of raw meat in the morning, sleep most of the day and sun themselves in the afternoons. Similar to the work of the dog sentries at Fort MacArthur but not connected with it dre the duties of a group of dogs that are guarding some of the depots of the quartermaster corps on the west coast. The dogs were trained and donated to the corps by Carl Spitz, Hollywood dog trainer. Spitz picks dogs that are about 25 inches in height and that weigh 80 or 90 pounds. He finds that purebreds are easier to train than most crossbreeds. German shepherds, collies, doberman pinschers, malamutes, and other working dogs take the work seriously and make dependable guard dogs. The dogs that he is training for military service are taught to regard with suspicion anyone who doesn’t wear a uniform. The first part of the schooling that Spitz gives his animals, of course, is the regular obedience training by which a dog learns to sit, drop, heel, stay, and come. Jumping over high and wide obstacles, carrying and retrieving objects, and barking on command are other parts of the course. The dogs learn how to search for a suspect who may have concealed himself, how to give an alarm, and how to attack. Part of his system is to teach the dogs to realize their own strength so that they will have the advantage of perfect confidence in a fight. Most dogs abhor smoke and noise and yet dogs in military service should carry on their duties in spite of such conditions. Accordingly the dogs are walked and rehearsed through clouds of chemical smoke and they are taught to work unperturbed while firecrackers, torpedoes and guns are discharged close by. To be able to control the actions of a dog far in the field, out of sight or hearing, Spitz has experimented with a short-wave radio, the receiving set of which is carried by the dog. Earphones may be used but the best results have been had with a small speaker built into thereceiver. Responding to the radio commands, the dog obeys just as rapidly and accurately as if his trainer were beside him. Armies in Europe have trained dogs to do many valuable duties. Finland, for instance, has a dog reserve in which the members are trained for service under battle conditions. Some of them are taught to operate while wearing gas masks. Dogs are reported to be used in England for guarding the invasion coasts, where their keen senses are especially useful during heavy fogs. It is said that Russia has a dog corps that is dropped by parachute along with regular paratroops for messenger work in the field. Being smaller and faster than a man, a dog makes a useful messenger that can cross open country with less danger of being hit. During the first world war one dog is said to have covered the three kilometers between posts 30 times in one day, travel- ing back and forth with messages in a container strapped to his back. Some of Spitz’ dogs have learned similar duties and are able to make their way from one point to another as far as three miles distant and even across strange country. A dog is twice as strong as a horse, relatively, and many of them have long and honorable military records for carrying cartridges and food to isolated outposts. Occasionally they have packed a cage of carrier pigeons that were later used for dispatching messages back. Carrying reels of light telephone wire, dogs have laid long stretches of communication networks. When the reel is attached to a light cart behind the dog he can pull a load that weighs upwards of 150 pounds at the start of the trip. Another chapter in the story of dog’s usefulness during war concerns his Red Cross work. A dog that is trained for this service abroad can seek out the wounded on a battlefield, stand by while an injured man helps himself to the supplies carried on the dog’s back, then return to headquarters and lead a stretcher party back | to the man he has found.

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1942-06

-

pagine

-

8-11, 164

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Enrico Saonara