-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Night watchmen of the skies

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Night watchmen of the skies

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

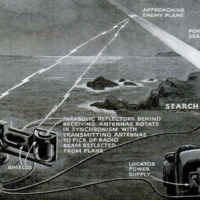

Ingenious machines crews in air-raid protection

DARKNESS and silence cover the scene

—the Coast Artillery area guarding a

seaboard city—and the activities

of the day seem long since to have ended.

But in an isolated section, far away from

the big-gun emplacements and the barracks,

a small group of men are engaged in quiet,

intense work. They are the watchdogs of

the Army, members of an antiaircraft

searchlight unit, whose job is to detect,

track, and illuminate raiding enemy planes

and keep them illuminated while crews of

antiaircraft gun batteries blast them from

the skies.

It is an eerie job. A layman observer,

permitted to witness a night of practice,

sees long lines of cables snaking through

the sandgrass, leading from an instrument

that looks like a botanist's nightmare—a

cluster of weird, mechanical bell-shaped

flowers—to other devices that appear squat

and formless in the dark.

He sees helmeted men attach themselves

to the flower cluster by means of thumb-

thick tubes, like an insect’s antennae, which

are fastened to each helmet's ears and con-

nect with the center of the instrument. He

watches the men twist wheels which ele-

vate the flower-shaped horns or turn them

horizontally.

He learns that the snakelike cables are

transmitting electrical impulses which car-

ry information to one of the squat instru-

ments, 500 feet away, where other men

turn wheels and fasten their gaze on dials.

He hears the chief of section of the unit

give a brief command and suddenly, from

a thing that has been dark and dead,

perched atop a sand dune, shoots a blinding

beam of light—and in the center of that

beam, thousands of yards from the ground,

the murderous throb of a bomber’s motors

is transformed in an instant into a clearly

distinguished plane. The target has been

“flicked” dead center.

To “flick” so fast and elusive a target as

a plane demands a high degree of codrdina-

tion and an immense amount of practice.

The problem of the Army's watchdogs, in

its essentials, is to pick up the sound of an

enemy plane as far away as possible, de-

termine its position and direction, track it

as it approaches, and illuminate it at the

earliest possible moment 80 that the gun-

ners of the antiaircraft batteries will have

‘something to shoot at.

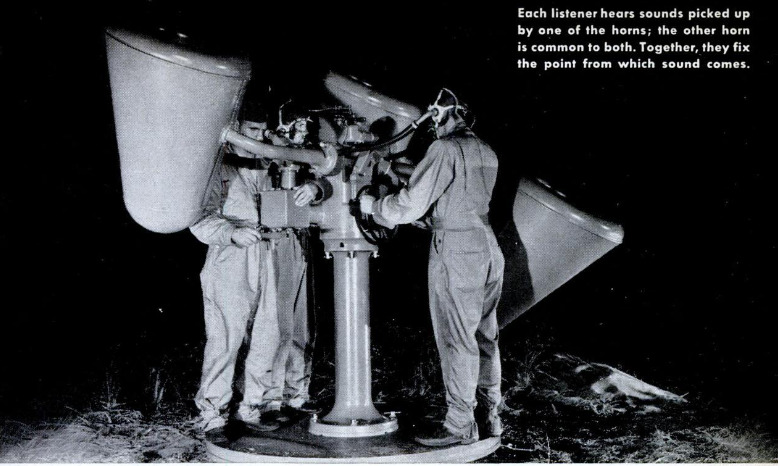

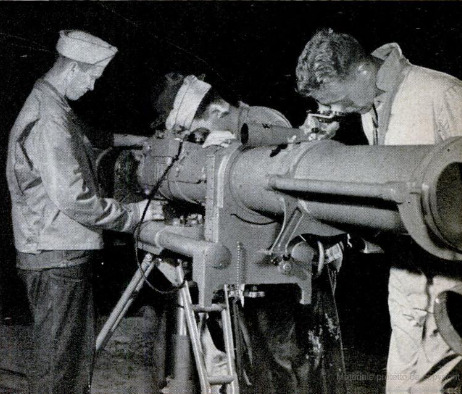

The first business in hand on this night

in the sand dunes is the botanist's night-

mare, the sound locator. In its newest de-

velopment this consists of three bell-shaped

horns attached to a metal column which

rests on a platform. The horns are designed

to act as huge extensions of the human ear.

The three horns form a triangle and the

middle horn is common to the other two.

That is, the middle horn is paired with the

bottom horn to obtain the elevation of a

plane, and with the top outside horn to

obtain azimuth, or the horizontal angle, and

thus establishes direction. The old-style

sound locator had four horns, two for eleva-

tion and two for azimuth, until it was dis-

covered that one horn could be made to

do the work of two.

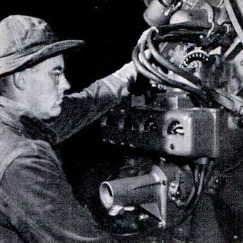

Two helmeted men, their headsets at-

tached to tubes leading from the hearing

mechanism, face each other on the plat

form. One, who is the elevation listener,

turns a small handwheel and raises or low-

ers the horns until the thrum-thrum-thrum

of the plane's motors seems to be directly

in the center of his brain, neither stronger

toward the left ear nor stronger toward the

right. When he has centered the sound he

knows he has the horns set correctly to ob-

tain the elevation of the plane.

Similarly, the second man, who is the

azimuth listener, turns his handwheel and

moves the horns in a horizontal circle until

he, too, has centered the sound in his head

and knows that he is on the correct azi-

muth.

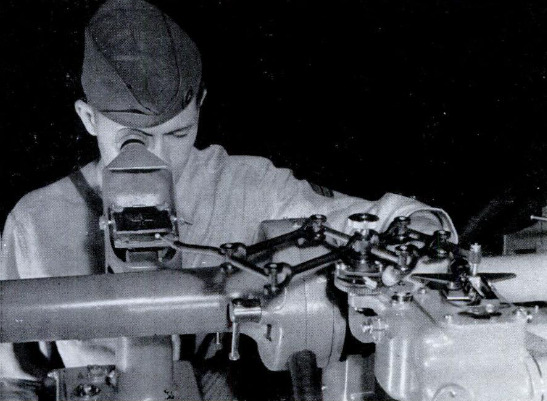

But there is one very important calcula-

tion still left out, which requires the pres-

ence of a third man, who is known as the

corrector operator. Since sound travels at

about 1,100 feet a second it is obvious that

when the hum of a plane's motors reaches

the locator, the plane has traveled a con-

siderable distance from the spot where the

horns would place it.

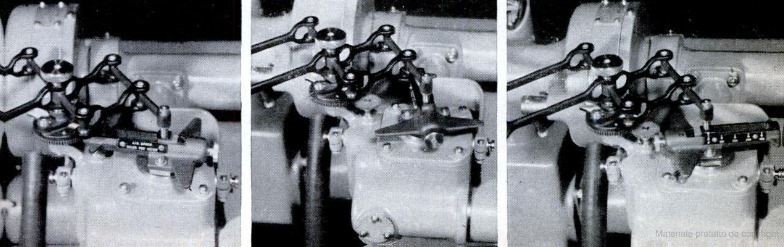

To correct this sound lag, a small device

known as a pantograph is a part of every

locator. The pantograph is geared to the

locator’s tracking mechanism. When the

corrector operator has centered the image

of a ball, which is on the end of the panto-

graph, between cross marks on a mirror, he

has automatically applied corrections for

sound lag, wind error, target speed, and

parallax error created by the distance

(ideally about 1,000 feet) between the sound

locator and the searchlight.

Just below the pantograph is another tiny

device, known as a course indicator. This

is in the shape of a miniature airplane and

is cobrdinated with the movement of the

horns to indicate the direction in which the

target is flying.

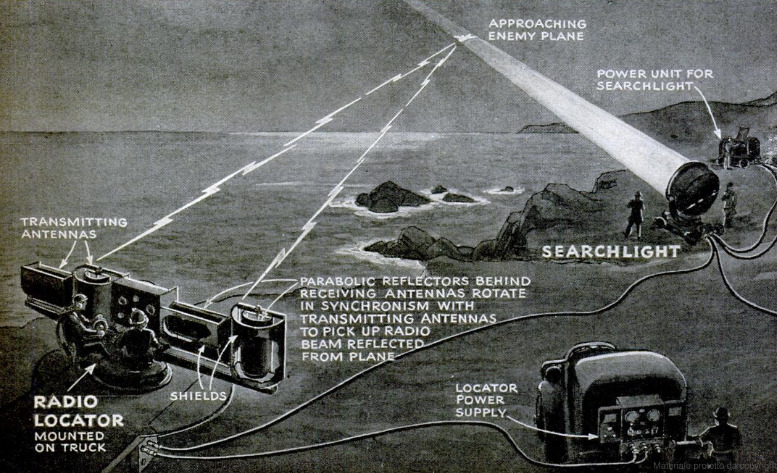

While the sound locator is an efficient in-

strument, the great speed of modern air-

craft makes its range too limited to be

completely satisfactory. The Army, there-

fore, is developing a new and secret device

about which no detailed information can be

given. This is a radio direction indicator,

based on the principle of similar devices

now being used by the British which are

said to be able to pick up an enemy plane

before it leaves the French coast and track

it across the English Channel. The range of

this radio locator is part of the Army's

secret, but it extends perhaps up to 100

miles.

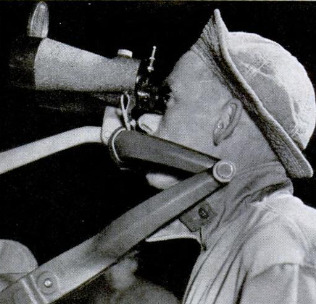

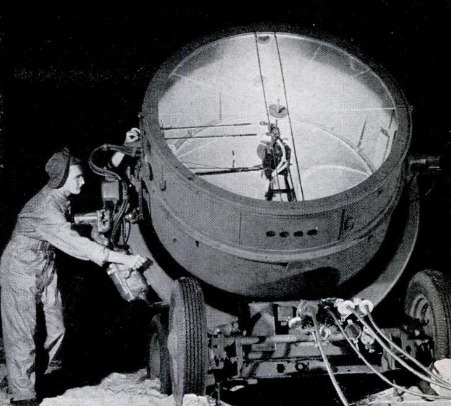

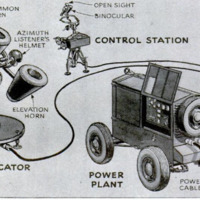

Cables from the binaural sound locator

described above lead to ‘the searchlight and

thence to an apparatus called the control

station, which is operated by three men.

The control station, by which the light is

moved electrically, is situated at least 50

feet and perhaps as much as 600 feet away

from the light. This enables observers to

see more clearly, just as a man will hold a

lantern away from him in order to avoid

being blinded by its rays.

The corrected data flow from the sound

locator to the control station where there

are an azimuth tracker and an elevation

tracker. Here handwheels are turned until

the azimuth and elevation dials correspond

to the information that is constantly com-

ing in from the locator. The light moves

correspondingly as the wheels are turned and

at the moment when the plane is believed

to be within range the light is turned on.

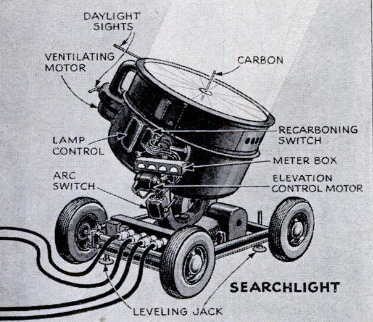

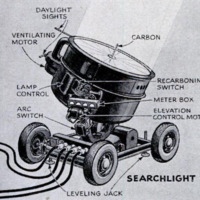

The antiaircraft searchlights send out a

‘beam of 800 million candlepower intensity

produced by a carbon arc burning in a cra-

ter, the light being reflected by means of a

parabolic metal mirror. The beam has a

range of from 5,000 to 12,000 yards, depend-

ing on atmospheric conditions. The light

may be operated manually, but usually is

controlled from the control station.

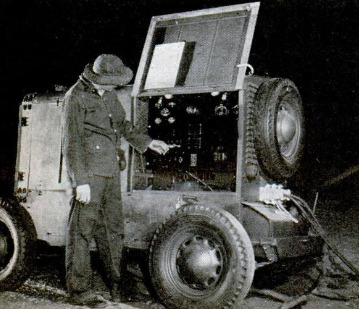

One other piece of apparatus is necessary

to complete the set-up of one

searchlight unit. This is the

mobile power plant, which con-

sists of an air and water-cooled

gasoline engine driving an

electric generator that deliv

ers about 150 amperes and 78

volts to the searchlight. The

power plant is placed, if pos-

sible, with a knoll or some

other obstruction between it

and the other apparatus to

eliminate its sound.

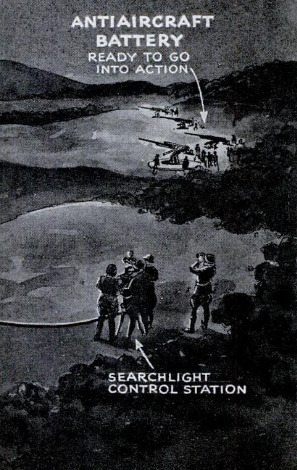

Once the lights get on a tar-

get the anti aircraft-gun bat-

tery goes into action. Contrary

to popular impression, there is

no close association between a

searchlight battery and a gun

battery. The two work sep-

arately, each with its own in-

struments. When a target is

illuminated, the crew of the

gun battery track it by means

of a stereoscopic height finder

and director, by which azi-

muth and elevation readings

are obtained. Firing data are

electrically transmitted to the

guns and set by members of

the crew by turning hand

wheels. The fuse of the shell

is cut to explode at the desired

height, and the projectile

streaks skyward,

So ends a practice night

with the Army's watchdogs,

as they practice their job of

guarding our night skies.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

John Watson (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1941-12

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

52-57

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 6, 1941

Popular Science Monthly, v. 139, n. 6, 1941