-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Grasshoppers: that's what the army calls its new odd job planes

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Grasshoppers: that's what the army calls its new odd job planes

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

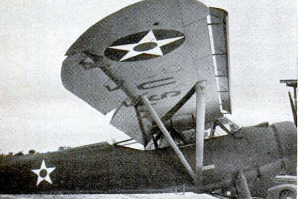

THE latest innovation in Army airplanes

is not a fast pursuit or a heavy bomber,

or anything else you would think of as

a military ship. It is that type of light

sportsman’s plane which, in bright hues of

yellow, blue, or red, has swarmed so increas-

ingly around the pasture-lot flying fields in

recent years—our familiar friends the Piper

Cub, the Taylorcraft, and the Aeronca.

The Army calls it a grasshopper, and it is

simply the stock-model tandem trainer of

these common commercial

planes. In its own way the

grasshopper is almost as

exciting and useful a mili-

tary newcomer as the ban-

tam car, the jeep, has

been. This flying jeep won

its spurs with the cavalry

last summer, and then in

the autumn gave such

service with the artillery

and the infantry that it

now seems to be slated for

permanent enlistment in

the armed forces of the United States.

Its use is for command-control message

carrying, observation, traffic direction, taxi,

and general-utility work—directly with

troops, behind the lines, wherever there is

a little field or open road for landing, where

bullets are not flying.

It is already in mass production, commer-

cially. This growing industry made 6,000

planes in 1940, and says this figure can

easily be doubled. Almost any enlisted man

can be trained to fly one in a few hours, and

thousands of qualified pilots are in the Army

already.

Striking power is only one of the things a

general has to worry about. Today's army

units move so fast, maps change so rapidly,

that it becomes a major problem for the

commanding officer to know where his

troops are—even before they have reached

the zone of combat. Roads and radio chan-

nels become jammed and bogged.

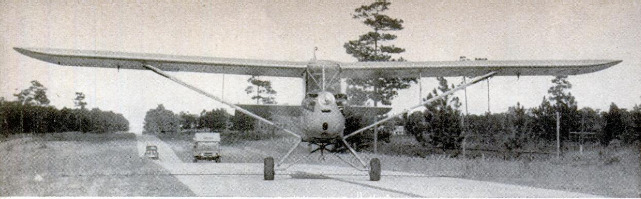

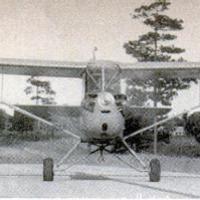

One obvious answer to this is the light

liaison airplane, able to take off and land on

a pocket handkerchief, able to fly so slow

and so low that messages and orders can be

shouted to troops on the ground—a hedge-

hopping plane for the Army's back yard.

Such a plane would be of little use on an

actual battlefield, for it can easily be

knocked down by small-arms fire, but for

work behind the lines it is invaluable.

Three specially designed planes of this

type, built by Bellanca, Ryan, and Stinson

to embody principles developed in Germany,

were put into service with the Army this

year, and quickly showed their usefulness.

With large wings, equipped with flaps and

slots to increase buoyancy at low speed,

these liaison-observation planes can perform

marvels—land and take off in about 250

feet, maintain flight at little more than 20

miles per hour. Against a brisk breeze they

can hover, almost stationary, over one spot.

But hardly had these special jobs made

their debut when they ran

into competition. The

small-plane manufacturers

bobbed up with the auda-

cious notion that their lit-

tle stock models could do

the same job just about as

well—and could be deliv-

ered, complete with two-

way radio, for less than

one tenth of the cost.

Meanwhile Bellanca, Ryan, and Stinson

might be building real military planes.

Led by the Piper Aircraft Corporation,

they proposed to give a demonstration of

their products. And so a special civilian

squadron was organized, of nine Piper Cubs,

two Taylorcraft, and two Aeroncas, to serve

during the summer in Army maneuvers in

Tennessee and Texas. The Grasshopper

Squadron, as it came to be known, was so

successful that the Army rented the planes

and hired the pilots for the autumn maneu-

vers in Louisiana. Meanwhile the Air Corps

purchased a number of the planes for testing.

The cavalry maneuvers in Texas were in

rough sand-dune country, covered with an

eruption of hummocks and hillocks. But a

single bulldozer, in 2 1/2 hours’ work, had

cleared a landing field good

enough for the grasshop-

pers. One of the lightplanes

washed out its landing gear

on a sand dune. It was back

in the air again in an hour

and 20 minutes, at cost of

$20 for repairs.

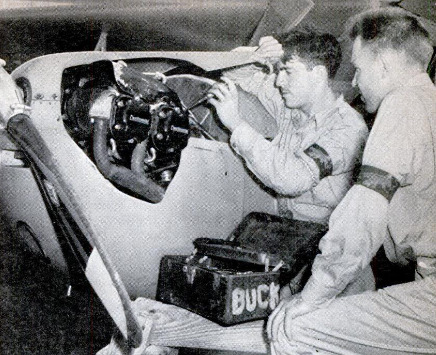

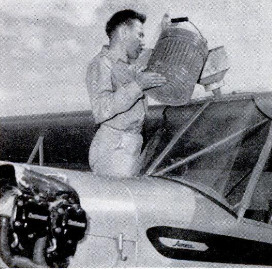

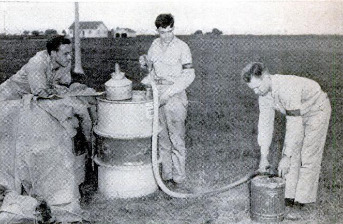

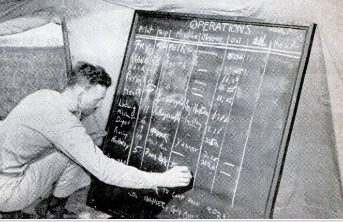

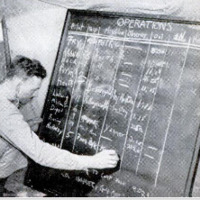

The field-base equipment

of the Grasshopper Squad-

ron was so simple that it

was almost ridiculous. It

consisted of a tent, a

small blackboard for an

operations chart, a couple

of boxes of spare parts,

and a poker table. The

ground crew consisted of

one mechanic, whose en-

tire tool kit was about

the dimensions of a man-

size dinner pail. It

needed no supply train

for aviation gasoline; it

poured in its fuel from a

five-gallon can, the same

gas that was used for

driving the Army trucks.

The squadron got its name in a tense mo-

ment of maneuvers one day when Maj. Gen.

Innis P. Swift, commanding the 1st Cavalry

Division, suddenly was seized with an urgent

desire to see more of his terrain than was

apparent from a staff car or the back of a

horse, or from the somewhat fragmentary

radio messages that were coming in.

“Get me one of those grasshoppers!” cried

the general. And within a few minutes he

had it, from the squadron's near-by flying

base. And the squadron men did not neglect

to notice that an Army radio message, noti-

fying the general that the plane was on the

way, did not arrive until 20 minutes after

the plane was on the job.

The general's happy description of the

little planes was immediately taken up by

the flyers themselves. They painted

green grasshoppers on their fuselages.

They had pins made up, showing a

comic little green grasshopper in a silk hat.

One of the proudest wearers of this Grass-

hopper Squadron insignia is Lieut. Col. T. H.

Kerschner, assistant chief of operations, G-3,

Third Army. Both as chief umpire and chief

of operations during Army maneuvers, he

used a grasshopper plane continually. Often

he completed an errand in a few hours,

which otherwise would have taken all day,

blocked in crowded roads or slogging around

in mudholes.

The piney woods country of Louisiana is

sparsely populated wilderness, but here and

there on the gravel country roads is an

isolated store, with a stock mainly composed

of canned goods, candy bars, soft drinks,

chewing tobacco, and snuff. More than one

backwoods proprietor of such an emporium

was startled during August and September,

by the apparition of an airplane outside his

front door by the gasoline pump. It was just

Colonel Kerschner stopping to refuel!

Almost every officer who has used a

grasshopper or seen it in operation is an

enthusiast for it. One Air Corps lieutenant

put it this way:

“I've been flying a Stinson 0-49, the new

liaison plane, and it is a sweet plane at

the job it was designed for. But the

grasshopper can do almost anything

the 0-49 can do, and more besides. I can fly

a little faster and a little slower, and the

grasshopper needs about half again as much

distance for landing and take-off. But it

doesn’t need to land in a small field, because

it can land on a narrow road. Its wing

spread is only 37 feet. Mine is 51 feet, which

is a lot of difference when you're figuring on

the width of a road.

“Also, the grasshopper weighs only 800

pounds unloaded. A pilot can land on a

road, and drag the plane off to hide it in the

bushes, all by himself. You can’t do that

with an 0-49. It weighs nearly four times

as much.”

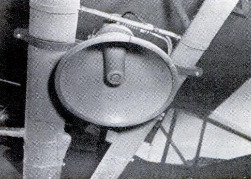

A more specific description, drawn up by

a proponent of the grasshoppers, is given in

an accompanying table. None of this, of

course, is to be taken as a knock at the 0-49,

which was built to high military specifica-

tions and has given splendid performance in

the tasks assigned it. Lieut. Gen. Walter

Kreuger, commanding the Third Army, used

one continually during the war games for

personal transportation and for watching

his troops in the field. With a loudspeaker

fastened under a wing, the Provost Marshal

found an O-49 very useful

in directing convoys on

congested roads.

The appearance of the

grasshoppers with the

Army immediately called

forth a flood of letters

from selectees with pilot's

licenses, who would prefer

flying to continuance as

infantry privates. One

thing that seizes the im-

agination of enthusiasts

about the lightplanes is

that it doesn't take much

training to fly them. They

foresee lightplanes, piloted

by noncommissioned offi-

cers, operating with

ground units, on practical-

ly the same basis as a

truck or a command car.

But one thing is settled.

Ground officers who have

worked with grasshoppers

want grasshoppers. And

when the troops want an

item of equipment, in these

days, they generally get it.

HICKMAN POWELL.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

63-67

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942