-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Boss of the big bomber

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Boss of the big bomber

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THREE years ago he was a young, raw

Army recruit. He knew a little about

mechanics and practically nothing

about soldiering. Today he is the “boss”

of a big bomber, the aerial engineer of a

B-17 Flying Fortress, and that ship is his

career—an Army career that has given

him the schooling and experience to fit him

for the same sort of job on a transoceanic

clipper or a big commercial land plane when

the emergency is over.

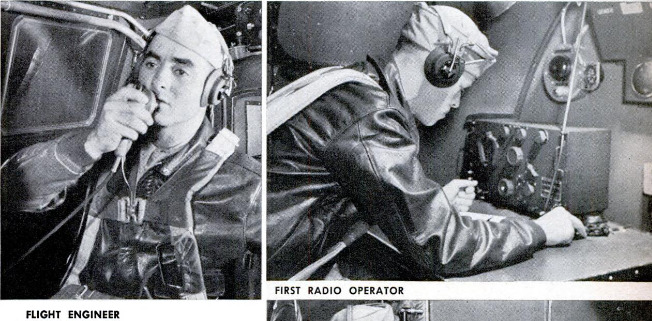

He doesn’t pilot a plane and he wears

only the stripes of a technical sergeant, but

he is an important man in the Air Corps.

He knows every rivet and gauge in the

bomber he grooms and broods over. Wheth-

er it is in the air or on the ground it is his

ship. The Army concedes that, and it is

just as well, for the aerial engineer would

not relinquish his proprietary rights in a

plane for all the armed forces of the nation.

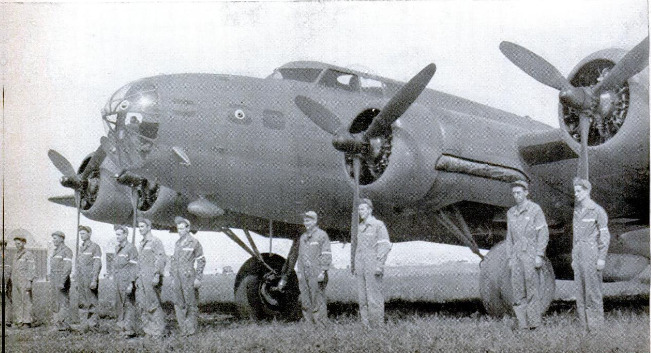

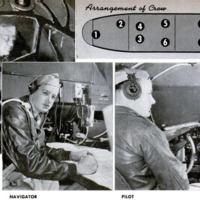

The mechanization of the Army has not

dehumanized it. Every Flying Fortress with

its four engines, its wing spread of 103 feet,

and its rudder that stands 20 feet high,

demands the complete understanding of one

man and that man is its aerial engineer.

The Army realizes this dependence and is

providing for the care of the monsters which

are being turned out in increasing numbers.

Enlisted men who are to be their nurses

already are assigned to the factories where

they are taking form, watching their de-

velopment from embryo.

‘Westover Field in western Massachusetts,

the $9,000,000 base for the heavy bombard-

ment groups of the Northeastern States on

which work was started 18 months ago, is

an example of the demand there is going

to be for aerial engineers. Westover has

only a few Flying Fortresses now; within

a year it will have between 100 and 200,

each of them dependent upon the affection-

ate and vigilant care of one man.

The Army is searching out these men and

training them. Some of them are still raw

recruits at $21 a month, getting their first

six weeks’ training in the rudiments of

soldiering. Some time during this six weeks

the recruit gets an aptitude test which will

show whether he is mechanically inclined

or otherwise.

That is the first step. The man whose

test shows a decided mechanical bent gen-

erally gets an opportunity to request as-

signment to the ground crew of an air

squadron. If he already has his eye on the

rating of aerial engineer, he asks for as-

signment to a transport, reconnaissance, or

heavy-bombardment outfit instead of to an

attack or pursuit squadron.

If his request is granted, he goes to the

squadron as a recruit and has the chores

of a recruit to do during his sizing-up

period. He gets kitchen-police and guard-

duty assignments, fatigue details, and po-

lices the field in general. He may be at these

jobs for days or weeks, and then comes an

opportunity to go to school and take a

course in aerial mechanical engineering

which would cost him at least $900 if he

undertook it independently.

First he takes an intelligence test and

then an examination in mathematics. The

examination is thorough and will reveal

any weakness in fractions, decimals, ratio

and proportion, square root, or elementary

algebra. When he has passed it he has the

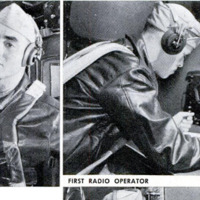

choice of several courses in Army Air Corps

technical schools—airplane mechanics, air-

craft armoring, machining, metalworking

or welding, parachute rigging, photography,

radio operation and mechanics, Air Corps

clerical work, and weather observation.

Scores of schools in various parts of the

country are giving these courses. Some of

them are private aviation schools which the

Army took over as they were, retaining the

civilian teaching staff and putting an Army

officer in charge. Some are strictly military

institutions. Their Army students number

more than 100,000 annually. At some bases

a third of the personnel was absent in school

at a time. The students pay no tuition.

They get their Army pay and board and

lodging.

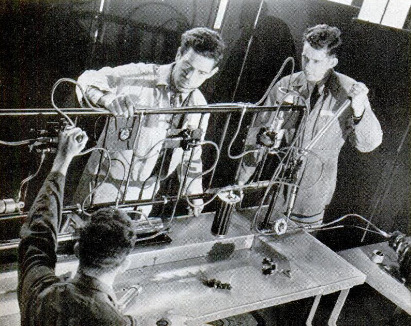

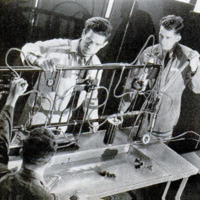

The airplane mechanic's course is the

one that leads to the job of aerial engineer.

It covers airplane construction principles,

maintenance and repair of a plane, its en-

gine and equipment, and the use of tools and

equipment in a hangar. The student is in-

structed in the operating principles and

repair of airplane instruments; the con-

struction principles and repair of the fuse-

lage, wings, and landing gear; the installa-

tion and care of de-icer equipment, hydrau-

lic systems, and pneumatic equipment; the

construction principles and repair

of propellers; the principle of the

internal-combustion engine; the

repair of storage batteries, gen-

erators, starters, spark plugs, and

wiring assemblies; and the tech-

nique of periodic plane inspec-

tions.

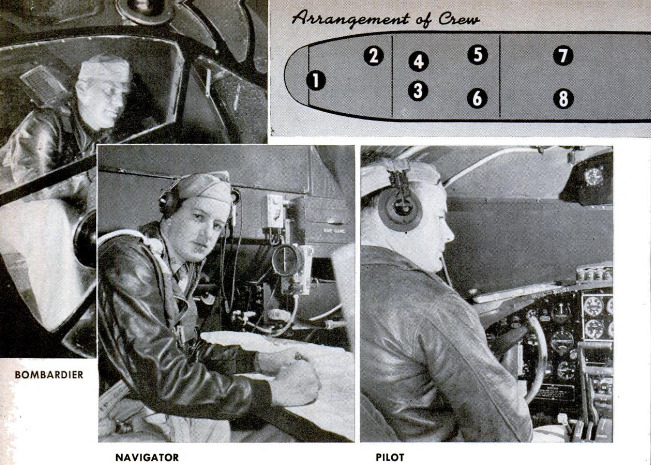

Graduates may take advanced

courses in the construction prin-

ciples and repair of carburetors

and airplane instruments, elec-

trical units and propellers, weath-

er forecasting and the care and

maintenance of the nation’s great

military secret, the American

bombsight. The bombsight, how-

ever, is not within the province

of the aerial engineer. Only two

men of the 250 in a squadron

handle that and they are chosen with the

strictest care.

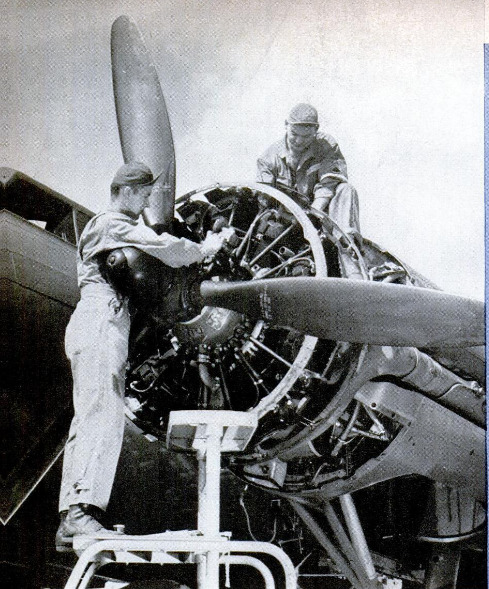

The school graduate returns to his squad-

ron as an apprentice mechanic, generally

with the rating of corporal, and gets his

first chance to do some work on one of the

big bombers. Again, however, he finds him-

self a beginner, with only the humbler tasks

assigned to him—chiefly, at first, the wip-

ing up of oil. The aluminum pistons of a

Flying Fortress do not fit the cylinders

closely until the heat of the running engine

has expanded them and until then the

engine sprays oil, distributing about a quart

over everything within range.

Kerosene cannot be used in cleaning off

this oil because of its inflammability. The

apprentice mechanic has to use carbon

tetrachloride, a vexatious fluid which evap-

orates at the first swipe. The oil sprayed

by the bomber's engines leaves a film even

in places seemingly inaccessible, and the

apprentice mechanic hunting it down be-

comes familiar with every part of the en-

gine mechanism—battery, fuel booster

pump, tachometer drive, carburetor control,

and piston. Tt is his job, too, to change tires,

wipe windows, wash the fuselage, and use a

vacuum cleaner. Every inch of the ship be-

comes familiar to him and he knows where

everything belongs.

On the first Mondays of June and Decem-

ber there are tests in theory and practice

covering the ground the apprentice mechan-

ic went over in his school course and if he

passes these tests he can qualify for the

rank of air mechanic, a rating which may

increase his pay considerably. An air

mechanic, second class, draws $72 a month,

which is as much as a staff sergeant gets.

An air mechanic, first class, receives $84 a

month, the pay of a technical sergeant. The

air mechanic, however, may still rank only

as a private. An able apprentice mechanic

may be able to emerge from that classifica-

tion within three months and become an

engine mechanic, one of whom services each

of the four engines of a bomber.

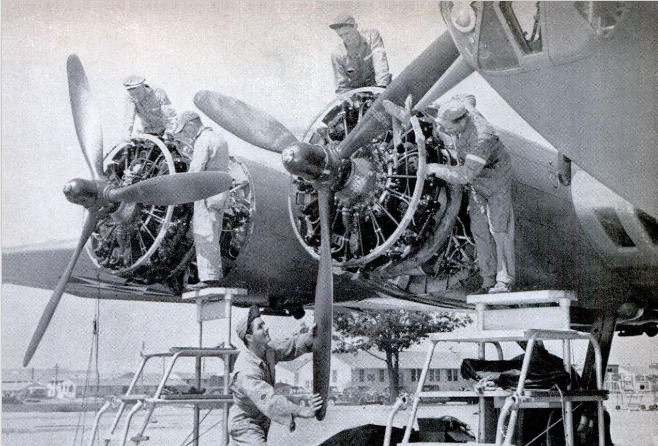

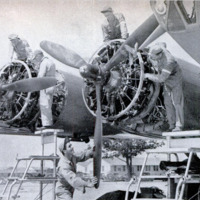

Each engine mechanic has full charge of

his engine and full responsibility

for its performance. He examines

every part of it daily. After every

flying period of 54 hours he chang-

es spark plugs and cleans ofl and

fuel strainers and inverters. After

350 hours, plus 20 percent if per-

formance still is good, the supercharger is

removed. After 450 hours the engine is re-

moved and sent away to be rebuilt.

The rapid development of the military

airplane has resulted in so many changes

in construction that the Army Air Corps

is assigning its expert mechanics to the fac-

tories which are turning out equipment for

it, the Glenn L. Martin Company in Balti-

more; the Consolidated Aircraft Corpora-

tion in San Diego; the Lockheed Aircraft

Corporation in Burbank, Calif.; the Curtiss-

Wright Corporation and the Bell Aircraft

Corporation in Buffalo; the Douglas Air-

craft Company, Inc, in Santa Monica,

Calif, and the Pratt & Whitney Engine

Division and the Hamilton Standard Pro-

peller Division of the United Aircraft

Corporation in East Hartford, Conn.

In peacetime it took two or three years

for an engine mechanic to take the next

step in advancement, that to the post of

ground-crew chief. It may be done now in

a few months. The ground-

crew chief, who stands next

to the pinnacle of aerial engi-

neer, generally commands the

rating of technical sergeant

and is at the head of a crew of

20 men—the four engine me-

chanics and 16 apprentices.

He makes a detailed inspec-

tion of the ship every day and

scrutinizes each of the engines.

At 50 hours he checks the

brakes, removes the wheels

and inspects the bearings,

washing them and repacking

them. At 100 hours he takes

off the tires and examines

them with care.

It may be only two or three

weeks before a ground-crew chief

gets an appointment as aerial en-

gineer, but the appointment does

not depend entirely upon his abil-

ity as a mechanic or the care he

lavishes upon his ship. Two other

qualities are of prime importance.

He must be immune to airsickness |

and must have deadly accuracy with a ma-

chine gun. Like the rest of the enlisted per-

sonnel of a Flying Fortress, he must rate as

an expert gunner to have a seat in his ship

in flight.

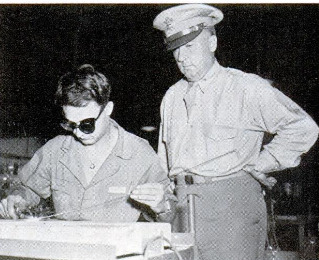

The aerial engineer does everything for

his ship except fly it. He probably could

fly it in a pinch, since he is so thoroughly

familiar with it. Before the ship takes

off he inspects every part of it and starts

the engines. On the new B-24's he will have

his own instrument panel to synchronize the

power of the four engines. Technical Ser-

geant Arthur E. Chatfield of the 34th Bom-

bardment Squadron at Westover thinks that |

it’s the power of the engines that commands

the loving respect of the aerial engineer. :

“When the pilot gives it the gun,” he |

says, “and it snaps you back in your seat,

you know you've got Something there.

Boy, you can tell that you've got some

horses in front of you!”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Barrett Mcgurn (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

Eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

90-95

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 1, 1942